Round Rock pediatrician Maria Scranton, MD, is one of several Texas physicians who speak wistfully about a temporary Medicaid physician pay increase under the Affordable Care Act.

In 2013-14, the federal law raised Medicaid primary care physician payments to Medicare rates, which Dr. Scranton says spurred increased access to care for Medicaid patients – some 30% to 40% of her patient population, along with those enrolled in the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) – and eased financial stress on physician practices.

Other than this brief reprieve, Texas Medicaid pediatric physician payment had remained at its original, subterranean level for nearly 15 years.

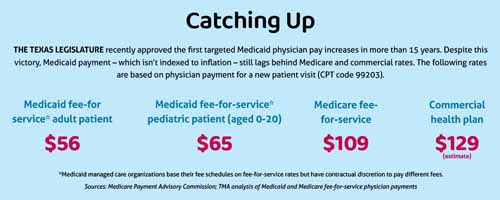

In 2009, a federal court consent decree resulted in lawmakers allocating funds to increase Medicaid payment for select pediatric services. But two years later, lawmakers enacted across-the-board Medicaid payment reductions. More recently, rapid inflation and rising costs have deepened these cuts such that Medicaid physicians aspire to Medicare payment rates, which also are in dire need of reform. (See “Catching Up,” page 17.)

“If we had started out in a house and were on the ground level with our rates, then it’s like over these past few years we’ve gone downstairs to the basement,” said Dr. Scranton, who chairs the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured.

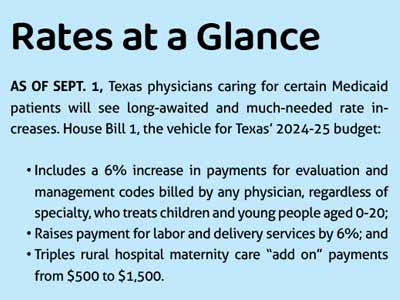

Fortunately, this changed during the regular 2023 Texas legislative session, during which lawmakers – led by Rep. Jacey Jetton (R-Richmond), Sen. Lois Kolkhorst (R-Brenham), and other members of the relevant budget subcommittee – approved a 6% boost to Medicaid physician payment rates to “improve access by children to physician and clinical services, especially well child visits,” according to House Bill 1, the vehicle for Texas’ 2024-25 budget.

This increase applies to evaluation and management codes billed by any physician who treats children and young people aged 0 to 20. The budget also included a 6% boost to Medicaid payment rates for labor and delivery services and tripled rural hospital maternity care “add on” payments from $500 to $1,500.

The updated rates took effect Sept. 1 and represent a huge win for Texas Medicaid patients and their physicians, says Gary Floyd, MD, TMA’s immediate past president. His term coincided with most of the regular session.

“Certainly the 6% [increase] is nowhere near Medicare parity,” the Corpus Christi pediatrician said. “But the 6% is the first rate increase for Medicaid in far too long.”

Dr. Floyd suspects the increases alone won’t pull new physicians to Medicaid. But he hopes they will be a lifeline to those already caring for Medicaid patients and weighing whether they can afford to continue doing so at the same pace or at all.

In the meantime, TMA continues to advocate strongly for additional increases, which Dr. Scranton says are necessary given both Texas Medicaid’s long history of stagnant physician payment and the limited scope of HB 1.

“Maybe with these rate increases, we’re going up a step or two to get us out of the basement,” she told Texas Medicine. “But we’re not even back to the ground floor.”

The budget also calls for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to evaluate any differences in access to care between patients aged 0 to 4 and those aged 5 to 20. HHSC will submit a report on those differences to Gov. Greg Abbott’s office and the Legislative Budget Board by Sept. 1, 2024.

Caitlin Flanders, TMA’s lobbyist on women’s health and budget issues, says this study is a key component of TMA’s ongoing advocacy for Medicaid physician payment reform.

“Unless we actually make [these increases and their impact on access to care] tangible, we’re not going to get anywhere,” she said.

Additionally, the TMA House of Delegates in May directed the association to convene a Medicaid Physician Legislative and Regulatory Panel, whose tasks will include “[identifying] services and populations for which targeted Medicaid rate increases will have the greatest likelihood of increasing access to care, health outcomes, and quality, while also being of the highest likelihood of enactment by state budget writers in 2025.”

“I know it feels like we just got out of the legislative session,” Dr. Scranton said. “But ... there’s no break for advocacy.”

Building momentum

The updated rates spotlight two areas of intense need, lay the foundation for expanded patient access to care, and signal an opening for more to come, says Sheila Magoon, MD, a family physician in Harlingen who serves on TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured.

“Our [South Texas] region has a high rate of Medicaid, so of course we would love to have Medicaid rate increases across the board,” Dr. Magoon said.

But because Medicaid is one of the state’s largest expenditures, Ms. Flanders says lawmakers often resist adding to the program’s expenses. This remained true during the most recent legislative session, despite a record-breaking budget surplus.

So, TMA had to be strategic, building on past legislative wins and lawmakers’ interest in improving maternal and child health.

For instance, the Texas House in 2019 approved a budget rider to increase payments by 7% for the care of children aged 0 to 3. But the rider didn’t survive budget negotiations with the Senate, and lawmakers instead opted to study whether such a rate increase would lower costs.

The resulting study, published by HHSC in November 2022, could not substantiate a link between rate increases and Medicaid cost savings within a two-year budget cycle. It did, however, underscore the importance of Medicaid physician payment, noting that paying more for preventive care and office visits “could be beneficial to improving the quality of care provided to Medicaid beneficiaries and could be associated with other positive indicators for Texas” (tma.tips/2022PediatricReport).

HHSC subsequently included in its 2024-25 budget request a recommendation that state lawmakers consider increasing physician payments for pediatric and women’s health services.

TMA also sensed an opening this session given the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization regarding abortion, which prompted lawmakers to look more closely at funding health services for women and children.

Six months later, the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee and the Texas Department of State Health Services jointly published a biennial report that found 88% of pregnancy-related deaths studied were preventable and Black women were disproportionately at risk (tma.tips/2022MMMRCReport). The report’s top recommendation was for Texas to increase the availability of comprehensive health care coverage during pregnancy, the year after pregnancy, and the childbearing years.

Armed with these findings and in the wake of the Dobbs decision, TMA swayed lawmakers to approve targeted rate increases by emphasizing the anticipated baby boom and long-standing access issues, exacerbated by Medicaid’s anemic physician payments.

“We need to take care of our women, and we need to take care of the children who are going to be born,” Dr. Magoon said. “There are going to be needs there.”

At press time, the updated rates had just taken effect. But Dr. Magoon anticipates the boost will be meaningful, especially to her fellow South Texas physicians and to pediatricians, given the high proportion of their patients enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP.

“That’s going to make a significant difference to your practice viability overall,” she said.

Ongoing advocacy

TMA already has acted to build on this success through the rulemaking process and other forms of advocacy.

Before the updated rates took effect, TMA urged HHSC to create a birth and women’s health surgery billing modifier to ensure the rate increases applied to all physicians involved in providing eligible labor and delivery services.

TMA President-Elect Ray Callas, MD, says such a modifier would have reflected legislators’ intent, for instance, by increasing payment for a cesarean section not only to the obstetrician but also to the anesthesiologist and any other specialists involved.

HHSC ultimately didn’t heed this recommendation. But TMA remains laser-focused on Medicaid physician payment reform for all physicians, regardless of specialty or patient population.

During the interim, the association is facilitating visits by interested state lawmakers to mobile women’s preventive health clinics in South Texas. The clinics are part of a Medicaid pilot program that received $10 million under HB 1.

Ms. Flanders says such visits could shore up support among Medicaid-skeptical lawmakers, which will be critical heading into the 2025 legislative session.

Dr. Magoon cautions that any benefits from this round of payment increases likely will be directly proportional to each other, noting the pay bump is small and may be complicated by other factors, such as the ongoing Medicaid eligibility redetermination process. (See “Coming Unwound,” page 26.)

Such factors make data all the more important, says Dr. Callas, which is why TMA intends to collaborate with HHSC as it studies the impact of the targeted rate increases on access to care among pediatric patients.

“TMA’s always been behind science,” he said. “We’ll be looking to make sure that access improves, that [maternal] mortality and morbidity improves, to know that we’re on the right path.”

At press time, TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured also was preparing to meet with delegates from state specialty societies in early October, its first step toward convening a Medicaid Physician Legislative and Regulatory Panel. The group will help shape TMA’s 2025 legislative agenda pertaining to where and how to target the next batch of Medicaid physician payment updates.

“For the next … session, we really felt like we needed to have more voices involved in the nitty gritty of it and understanding all of the statistics and the facts of what we were dealing with,” Dr. Scranton said.

TMA President Rick Snyder, MD, says such a multipronged approach is warranted given the stakes.

Across Texas, some rural hospitals at risk of closure have stopped providing labor and delivery services, in part because of low Medicaid payments. (See “Maternity Deserts,” June 2022 Texas Medicine, pages 40-43, www.texmed.org/MaternityDeserts.)

For the same reason, Dr. Snyder says many Texas physicians are weighing whether to continue caring for Medicaid patients, given the financial risk it poses to their practice. Without hospitals and physicians who accept Medicaid, the program loses its utility.

“Coverage is not the same thing as access,” he said. “Access to a waiting list is not the same as access to health care.”