For the past three years, Austin pediatrician Maria Scranton, MD, had a pretty sweet deal when it came to getting psychiatric advice on behalf of her patients.

She worked with a psychiatrist friend who promptly and without charge answered questions about psychiatric care – like whether a patient might need a certain medication, or whether the patient should be referred to a counselor for more in-depth care.

Dr. Scranton says her friend was glad to help, but their informal partnership ended earlier this year when the psychiatrist moved out of state.

“I kind of took advantage of that [relationship],” she said. “But I always thought this would be great if it could be more formalized.”

Soon, she’ll get her wish. The Child Psychiatric Access Network (CPAN) plans to start operations in May, giving pediatricians and family physicians across Texas free telemedicine-based consultation and training on community psychiatry.

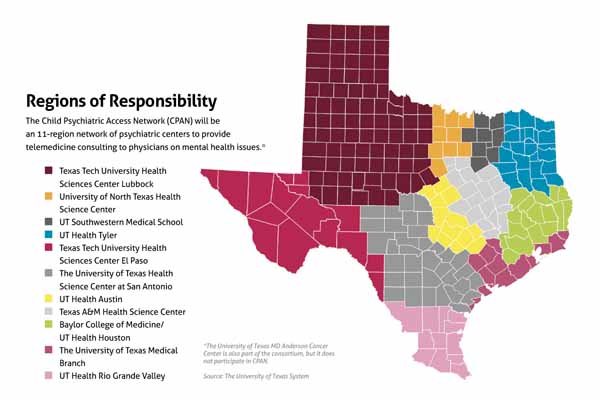

CPAN will work very much the way Dr. Scranton’s friend did. Pediatricians and family physicians who are stumped about some aspect of psychiatric care can call an academic health center in their region to get the advice they need, says David Lakey, MD, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer for The University of Texas System.

“The goal isn’t to replace that pediatrician or that family practitioner,” Dr. Lakey said. “It’s to equip them to take care of these patients. Let’s say that a pediatrician has someone in his office who needs additional care. He’ll call the academic health science center that’s responsible for that part of the state. The goal will be that within 30 minutes the psychiatrist will be on the phone and the psychiatrist will guide that pediatrician through the care.”

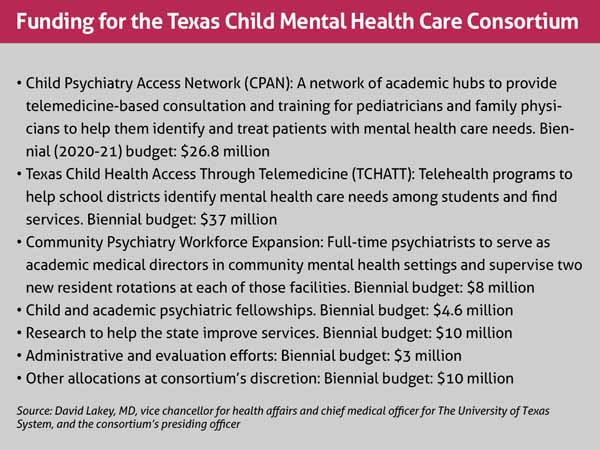

CPAN is a key part of a much larger mental health initiative created by the 2019 Texas Legislature called the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium. (See “Funding for the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium,” page 45.) Aside from CPAN, the consortium also will help public schools respond to mental health needs among students; expand the psychiatric workforce by paying for psychiatric positions and fellowships; and provide money for research on mental health in Texas.

Texas urgently needs all of these services because the shortage of psychiatrists is so acute that waiting lists can be months or even years long, and Texas ranks last among the 50 states and District of Columbia in access to mental health care, according to the nonprofit Mental Health America.

Moreover, most Texas primary care providers are not trained for or don’t feel comfortable handling behavioral and emotional problems in young people, says Nhung Tran, MD, a developmental-behavioral pediatric specialist in Temple. As a result, many physicians and other health care professionals may undertreat – or not even recognize – behaviors that need attention, she says. Others may overtreat normal behaviors or over-refer patients to busy psychiatrists and counselors.

“The mental health care consortium is addressing this extreme unmet need for identifying [problems] early in the hope of preventing behavioral and emotional issues [for patients later in life],” she said.

Many needs to address

Dr. Tran testified before the 2019 Texas Legislature on behalf of the Texas Medical Association, the Texas Pediatric Society, and the Federation of Texas Psychiatry in favor of the consortium, which was ultimately created under Senate Bill 11.

The broad nature of the bill shows just how much needs to be done to improve mental health care in Texas, says John Zerwas, MD, the former state representative from Richmond who sponsored the consortium legislation in the House. He is now executive vice chancellor for health affairs for the UT system.

“It’s a reflection that there’s not any one thing to address this need out there,” Dr. Zerwas said. “There are multiple things that need to happen to build on the availability [of mental health services]. That’s why you see multiple touchpoints.”

The legislature allocated about $100 million to the consortium, and about $90 million has been designated so far to the various programs by its 35-member executive committee. That committee is made up mostly of physicians from academic health sciences centers across the state, says Dr. Lakey, a committee member and the consortium’s presiding officer. Consortium programs are funded through the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board but administered by the UT System.

CPAN is one of the consortium’s biggest elements, and it is based on a model started in Massachusetts in 2004 and now copied in 36 other states, according to Laurel Williams, DO, chief of psychiatry at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and an associate professor at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Williams co-chairs the executive committee work group formed to develop CPAN.

CPAN will be different in some ways from the Massachusetts model because Massachusetts is a smaller state with a denser population, says Dr. Tran. (See “Regions of Responsibility,” above.) However, mental health professionals from Massachusetts and other states are helping Texas set up its program to “keep us from reinventing the wheel,” she said.

CPAN is a long-term investment – one that is unlikely to have an immediate impact on older adolescents who already show serious mental health problems, Dr. Tran says. However, the program will help identify mental health problems in younger children and, as those children grow, give health care professionals the skills they need to treat them.

For instance, she hopes the program will eventually help lower Texas’ suicide rate – the second-leading cause of death among Texans ages 15 to 24, according to the Department of State Health Services.

Pioneering effort

Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine (TCHATT), another major element of the consortium, will use telemedicine to help psychiatrists go into school districts to assess elementary through high school students with mental health needs. With the permission of the student’s family, a mental health clinician will use up to four telemedicine visits with a student over two months to address urgent mental health needs and provide treatment aimed at stabilization.

“It is a limited service,” says Sarah Wakefield, MD, chair of the department of psychiatry at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) School of Medicine in Lubbock and co-chair of the TCHATT workgroup. “It’s an assessment to see what’s going on with the kiddo and some brief treatment. And if that’s all that’s required, they’ll be discharged. If the student needs ongoing services, then the TCHATT program can help link them back with their primary care physician with recommendations or with a community psychiatrist or therapist.”

Currently, three medical institutions in Texas – The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, and TTUHSC – provide mental health services directly to school districts through telemedicine, Dr. Wakefield says. However, taking psychiatric telemedicine services directly into schools across the state is a first, Dr. Wakefield says.

“I have no doubt it will be successful,” said Dr. Wakefield, medical director of the telemedicine program at TTUHSC. “But no other state has done this, so we will learn from each other as we go.”

Because of its pioneering nature, TCHATT will take longer to start up than the other programs, Dr. Wakefield says. Many services are targeted to begin by the 2020-21 school year. And though TCHATT will be available statewide, the program does not yet have the funding or personnel to be available for every school in the state, she says.

Two other parts of the consortium will boost the number of psychiatrists helping young Texans.

First, the Community Psychiatry Workforce Expansion provides funding for additional psychiatric help for 17 of Texas’ 40 local mental health authorities. Beginning in July 2020, the program will provide funding for the equivalent of 12.25 academic faculty and 20 additional psychiatry resident positions at local mental health facilities. Consortium funding also will supply 19 new two-year fellowship positions and four new child and adolescent training programs.

Second, the consortium will develop statewide research networks within each of the participating academic institutions. Their research will focus on ways to advance the delivery of child and adolescent behavioral health care, the consortium’s implementation plan says.

Research is important to the consortium “so we can figure out how we can get smarter in the provision of this care,” Dr. Lakey said.

Tex Med. 2020;116(5):43-45

May 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page