Elderly woman. Low-income. Chronic pain. Needs to see a rheumatologist. Needs physical therapy. Struggling to pay rent. Has no insurance. Has no disability coverage.

As a family physician at a federally qualified health center (FQHC) in Austin, Sharad Kohli, MD, sees a lot of cases like this. In similar health care settings, the patient might face two bad choices: wage bureaucratic war to obtain better health care benefits or simply give up.

At People’s Community Clinic, Dr. Kohli referred her to an in-house lawyer who successfully appealed her denial of disability insurance.

“[The lawyer] got her a significant income, which allowed her to pay her rent and also helped her get insurance through Medicaid and Medicare,” Dr. Kohli said. “And then she was able to see the rheumatologist and the physical therapist.”

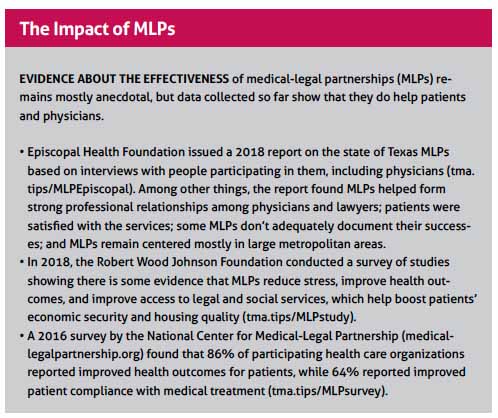

This kind of success helps explain why medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) like the one at People’s Community Clinic came about in 1993 and began expanding nationally after 2001. Texas has 10 MLPs – all in large or medium-size cities and all tied either to hospitals or FQHCs like People’s Community Clinic, according to the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership in Washington, D.C. Texas MLPs stand among 333 nationwide.

Given the relative scarcity of MLPs, most Texas physicians have no experience in coordinating patient care with a lawyer.

“This is the first place I’ve ever worked with a lawyer, and to me it’s been mind-blowing,” Dr. Kohli said. “A lot of times in the past I was just frustrated. I didn’t know what to do. And now we can have a lawyer here who can say, ‘Here’s what we can do. Here’s the next step.’

“These are lawyers who are really a member of the health team,” he added. “For me, it’s an opportunity to have [the patient’s] needs met, to have good communication, and it’s another team member that I trust in the clinic.”

An MLP can form when at least one medical entity creates a formal relationship with at least one legal entity in an effort to improve health care, says Tanweer Kaleemullah, a lawyer and policy analyst with Harris County Public Health who has been co-leading a statewide coalition of MLPs.

Some MLPs, like the one at People’s Community Clinic, have full-time lawyers on staff who work directly with physicians (tma.tips/PeoplesClinic). Usually the doctor-lawyer relationship is looser, however, and the legal help often is done part-time or with the help of volunteers.

Despite their diverse structures, MLPs tend to do similar types of legal work on behalf of low-income patients, says Mr. Kaleemullah. Some issues are tied directly to a clinical visit, like preserving health insurance or fighting the denial of prior authorizations. Others can include housing, transportation, wills, and guardianship.

The physicians are familiar with the lawyers, and that makes it much easier for both the physician and patient to trust that the legal work will help the patient, says Celina Beltran, MD, a family medicine specialist and medical director at the El Paso FQHC Centro San Vicente Family Health Center.

“Since we’re the primary care provider, [patients] feel comfortable coming to our center, and they feel comfortable letting us in and letting us know what’s going on in their lives,” she said. “So this enables us to take that one step further and help them from a medical and legal perspective. And overall that has a huge impact on their daily lives and, of course, ultimately on their health.”

Beyond the exam room

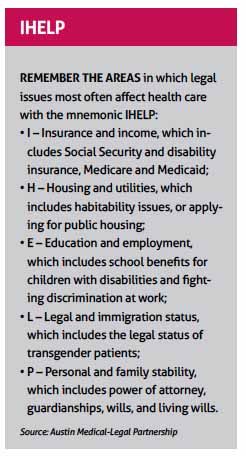

MLPs often help physicians cope with the social determinants of health – the factors outside the clinic that affect a patient’s well-being. Most cases deal with public benefits, housing, education, and guardianship, along with immigration and special education. (See “IHELP,” page 38.)

For instance, a typical MLP case might involve a low-income family living in an apartment where mold is making a young person sick, says Keegan Warren-Clem. She is an Austin lawyer and founding director of the Austin Medical-Legal Partnership, a collaboration begun in 2012 between two nonprofits – People’s Community Clinic and Texas Legal Services Center.

“If we have an asthmatic child whose physician is prescribing oral steroids and inhalers, and he’s still going to the pulmonologist, still presenting in the emergency room, still missing school, and mom and dad are missing work, what we need to be doing is looking at what is going on in the environment that is the root cause,” she said. “In this case, an attorney has tools to ensure that, for example, the landlord is following state and local laws that promise clean living conditions.”

The People’s Community Clinic MLP has three lawyers contracted to provide full-time legal care. Each lawyer sits in on patient conferences with the entire health care team made up of physicians, nurses, social workers and others, Dr. Kohli says.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston takes a different approach. It partners with the nonprofit Houston Volunteer Lawyers to provide one full-time and one part-time lawyer to help screen patients with legal needs. Those two lawyers handle some cases directly, but most of the work is handed off to area lawyers working pro bono.

Tom Mendez, the full-time lawyer, says this gives Texas Children’s two advantages: It can call on a large pool of legal talent, and it can find lawyers who specialize in the area of law that’s needed, such as housing or benefits.

Lawyers and physicians have to get used to working with each other, he says, and some physicians see lawyers as adversaries, not allies. So MLP lawyers say they take the time to train doctors and health care staff.

“Part of the work we do is educating the health care providers about the services that we offer – the types of issues that families often see that we can assist with,” Mr. Mendez said.

The cases that come up most frequently for Texas Children’s involve guardianship, physicians there say. For instance, when a minor with developmental disabilities turns 18, a family member may need to be named guardian to care for him or her, or the family may try an alternative to guardianship. In many cases, low-income families would not be able to afford to hire a lawyer on their own for this process.

Culture of advocacy

While helping individual families is important, MLP lawyers also allow medical practices to go a step further by influencing public policy. For instance, in 2018 the lawyers at People’s wrote a letter on behalf of the physicians there opposing the “public charge” rule, Dr. Kohli says.

That rule by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration redefines how immigration officials will classify many legal immigrants as a public charge, or dependent upon public services, when determining citizenship. The rule is widely expected to discourage legal immigrants and their families from seeking medical care. Virtually all physician professional groups – including the Texas Medical Association – have called for it to be withdrawn. (See www.texmed.org/PublicChargeRule.)

“If we really want to be addressing social determinants, which we know affect health in such an important way, we have to actually go further upstream, and the lawyer allows us to do that,” Dr. Kohli said.

People’s Community Clinic plans to hire more lawyers soon thanks to new partners and new funding. But keeping the lights on in the early days of the MLP was rocky, says Ms. Warren-Clem. Many MLPs still find it hard to generate funding.

For instance, Centro San Vicente in El Paso has partnered since 2009 with Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, which until recently provided a lawyer every Friday for patients to consult with. However, the lawyer can now come only every other Friday because of lost grant money, Dr. Beltran says, and that means fewer patients will be able to get assistance.

“It’s a service that’s very much needed,” she said. “It’s been a tremendous help to many of our patients.”

In 2018, Texas MLPs formed a statewide group, the Texas Medical-Legal Partnership Coalition. The group aims to increase the capacity of existing MLPs, says Mr. Kaleemullah, who helped organize the coalition. It also was created to help anyone starting an MLP and to influence public policy. (See “Starting a Medical-Legal Partnership,” below.) The group holds monthly meetings among lawyers and quarterly meetings that include physicians.

When People’s Community Clinic created its MLP, some board members expressed concerns that offering legal services constituted “mission creep” for a medical clinic, says Ms. Warren-Clem.

However, as with most MLPs, patient care comes first, and physicians have the final say, says Dr. Kohli. If legal services are deemed necessary, it’s the physician who makes a referral through the patient’s electronic medical record.

“It’s the same as if you made a referral to behavioral health in-house,” he said.

Tex Med. 2019;115(10):36-38

October 2019

Texas Medicine Contents Texas Medicine Main Page