There’s something to be said for trial by fire, right?”

That’s how Tina Philip, DO, summed up her spring.

On March 16, with the COVID-19 pandemic on the rise, the Round Rock family physician opened her new solo practice. A week later, Williamson County issued a stay-at-home order; a similar statewide order followed shortly thereafter.

For Dr. Philip and many other Texas physicians who suddenly couldn’t bring in their patients for routine visits, telemedicine became the only option. If those physicians had no experience with the technology, well, no matter. The choice was clear: Jump into telemedicine as best you can, or shut down and weather an indefinite zero-revenue existence that might put your practice in the ultimate jeopardy.

Dr. Philip chose the former. So did many of her fellow Texas doctors, with results both practice-saving and confounding at the same time.

“Telemedicine was one of those things I’ve been thinking about doing for a long time, but the pandemic was a good push to [say], ‘OK, we just need to do this,’” she said. “It’s been good in some sense to be forced to just do it and to adapt and change with the times.”

For Frisco pediatrician Seth Kaplan, MD, the transition to telemedicine was “zero to 60.” Many others did on-the-job training and were able to avoid financial disaster, learning lessons about their patients, their practices, and technology along the way.

Going forward, medicine will have to ask of telemedicine’s new, broader role in health care: Is it here to stay? Or is its rise merely the product of temporary, extraordinary circumstances? Physicians tell Texas Medicine that depends how telemedicine will be regulated and paid for.

Pre- and post-COVID telemedicine

During the 2017 legislative session, the Texas Medical Association achieved coverage parity – meaning health plans must pay for telemedicine visits for a covered service – as part of sweeping legislation that provided a framework for telemedicine in Texas. (See “Clearer and Simpler,” August 2017 Texas Medicine, pages 38-39, www.texmed.org/SB1107.) But that law didn’t mandate payment parity – meaning health plans didn’t have to pay a physician the same for a telemedicine encounter as for a similar in-person visit.

In addition, government and commercial health plan pre-pandemic requirements on how telemedicine could be used, including security and patient/physician site requirements, largely limited its use.

When the state and the federal government eased regulatory payment barriers to delivering medical care via telemedicine during March and April, it was an immediate boon for otherwise-sidelined physicians and their patients.

For the duration of the public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) relaxed certain regulations so “all beneficiaries across the country can receive Medicare telehealth and other communications technology-based services wherever they are located.”

Those loosened regulations, including certain temporary HIPAA relaxations, paved the way for remote visits using devices both patients and physicians were likely familiar with. Medicare also greatly expanded payment for these telehealth services.

Many of the largest commercial health plans either adopted CMS guidelines or waived requirements for key aspects of telemedicine, such as restrictions on the “originating site” of a virtual visit, meaning the location of the patient.

Also, temporary Texas Department of Insurance (TDI) rules mandated payment parity for telemedicine visits for a period of up to 120 days. TDI said that rule could be extended for an additional 60 days if needed.

Texas physicians who needed those simpler and more enticing changes to jump into telemedicine did so to both good and frustrating effect.

Some had telemedicine video platforms already in place as part of their electronic health record (EHR) software. Others, like Dr. Kaplan, had to select and purchase a platform. He settled on a pediatric-specific one that he hopes will leave him well-positioned to continue practicing telemedicine in the future. He and his staff trained for about a week familiarizing themselves with the software and making practice calls before going live.

For Neurology Consultants of Dallas – a 15-physician single-specialty practice that shut down all of its in-person visits before stay-at-home orders were issued – telemedicine implementation took a few days. Fonda Chan, MD, says learning to use the platform the practice chose was easy. The hard part was everything else.

“We had to convert all of the appointments to telemedicine because of COVID, and we have to explain it to patients and teach patients how to use it. That’s more of the bottleneck,” she said in early May. “From the billing and reimbursement perspective, we’re still learning about it.”

In a number of cases, physicians like Austin rheumatologist Brock Harper, MD, found themselves playing amateur IT consultants for patients. Dr. Harper had some telemedicine experience from a previous job serving a prison population, but that didn’t prepare him much for what he encountered this spring at his practice, Austin Diagnostic Clinic (ADC).

While he said telemedicine was “a lifesaver” for ADC and many others, transitioning to it wasn’t seamless, and helping patients troubleshoot remotely could be challenging.

The good

In the midst of the pandemic, telemedicine accounted for about 50% of Dr. Kaplan’s practice volume. Not only did it help keep him afloat, it also gave him an illuminating look into his young patients’ lives.

“When you’ve got a kid with ADD (attention deficit disorder) and you see into their house and the kid’s room is an absolute mess, you get more reasons as to why you’re dealing with the issues you’re dealing with,” he said.

Telemedicine also provided specific benefits for Dr. Chan’s patients. She’s an epileptologist, so her patients’ conditions limit their ability to drive to appointments. A remote visit presents an attractive alternative for those patients who otherwise would have to find transportation. Because of that, she had wanted to implement remote visits for some time.

“Some of them travel three, four hours to see me. It takes a whole day out of their life, and their family [member], whoever is driving them,” she said. “A lot of my patients fall in that category.”

One particular epilepsy patient with frequent seizures stuck out to Dr. Chan as someone who benefited greatly from the telemedicine adoption.

“We have [had] to try three different new medications before we found the correct regimen out [to] help her. Telemedicine allowed us to address that pretty promptly within two or three weeks, whereas a traditional face-to-face visit would actually not allow that to happen,” Dr. Chan said. “Every time she’d have to come in to see a doctor, she’d have to arrange for a ride.”

Little Elm Medical Clinic had implemented telemedicine before the pandemic, but COVID-19 pushed the practice to use it for every visit. Internist Jill Wolf, MD, encountered one patient with a rash who illustrated how video can be so much more helpful than even a simple phone call.

“She’s not a native English speaker, and she kept saying that something was on her hand. When we got her connected on the video call, it was actually her upper arm, not her hand at all,” Dr. Wolf said. “It was nice to be able to see what she was talking about, because she was having a hard time describing it to me. Otherwise, she would’ve had to come into the office. Because she had other underlying conditions, that would’ve put her at more risk.”

Physicians told Texas Medicine that patients’ willingness to use telemedicine was generally high, aside from some reluctance predominantly from older patients.

“There were some patients that were not entirely happy to not be able to come in, but they understood that the risk was greater than the benefit,” said Denton obstetrician-gynecologist Joseph Valenti, MD. “There was a whole other subset of patients who were just happy to be able to talk to their physician and get refills on prescriptions or go over a problem or just voice a concern. So they had that feeling of outreach that they can talk to their clinical physician and get a result of some sort. I would say most people were pretty happy about being able to have access to care where they otherwise wouldn’t.” (See “On Pause for the Pandemic,” page 22.)

The struggles

Connectivity problems did surface, however, illustrating the lack of adequate broadband access particularly in Texas’ rural areas. Dr. Chan noted that her rural patients have more noticeable connection problems.

For Dr. Harper: “I’d say it’s a third at least of the patients [where] there’s been some sort of technical issue. But it’s rather rare to have somebody where we just couldn’t do the visit at all because of it.”

Odessa endocrinologist Rama Chemitiganti, MD, is regional chair for the department of internal medicine at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, a longtime advancer of telehealth technology. Not only is broadband access a struggle for rural parts of the U.S., but there’s also a personal preference in his area working against telemedicine adoption: Patients in West Texas “still like to drive” and don’t mind coming in from long distances for an in-person appointment, staying the night, and making an outing of it.

“If there is not enough demand for broadband cables to remote areas in a state as big as Texas, it is going to be challenging,” he said.

Texas physicians are trying to tackle that problem as part of Gov. Greg Abbott’s Broadband Development Council, created during the 2019 legislative session. Several TMA members serve on the council.

Meantime, Dr. Chemitiganti said, “cellular technology is here and now. Increasing the use of cellular technologies [for] patient care would be a good fix until we can get that broadband access improved.”

Dr. Chan says technical difficulties haven’t resulted in a cancelled visit, but they have required detective work to sort out, such as when a patient called Dr. Chan for a video visit from his truck and could not get the audio working. Eventually, they figured out the Bluetooth audio from his phone was connecting to his truck’s speakers when he turned the ignition on, so he had to keep the car turned off for Dr. Chan to hear him.

And Dr. Kaplan says telemedicine visits are taking more time than the same sort of visit would take in person.

“Our system that we’re using is not integrated with our EHR, so I’ve got the video going on one screen and then I’ve got my EHR open right next to it,” he said. “For me, I’ve got my EHR so efficient that when I’m in-person and I finish the visit, there’s maybe a minute left of typing I have to do. With this, I’m finding it’s taking me longer to get my EHR note done. And we’ve figured out that I can’t open my e-prescribing screen in my EHR while I’m in the telemedicine visit, or it crashes the video.”

Aside from those complications, video simply can’t replace some aspects of patient visits. For instance, Dr. Kaplan says rashes are hard to see on the screen, and he’s found it’s better if patients take a picture of the rash and submit it through the patient portal.

“But unless you spend money on one of these [more advanced telemedicine] kits that are out there, you can’t listen to lungs, you can’t look at ears, you can’t look at throats very well. But we get creative, too,” Dr. Kaplan added. “We’re able to walk them through [some] stuff. It’s just not ideal.”

Payment parity

Once the pandemic is in the nation’s rearview mirror, questions will abound for the extent of telemedicine’s role in patient care. Will the “zero to 60” approach of spring 2020 make telemedicine one of the frontrunning cars on the care delivery track? Or will it fall back among the pack, as physicians revert to traditional modalities and workflows?

One of the biggest factors in answering that question will be whether payment parity for telemedicine visits can be made permanent and more pervasive. Dr. Harper says this year’s events have probably opened a lot of eyes to the usefulness of telemedicine.

“It’s less patient or doctor enthusiasm for [telemedicine] that’s shackled it, and more the regulations that were surrounding the payment, in particular from a Medicare perspective,” said Dr. Harper. “That always made it a challenge to justify doing the infrastructure and training and readjusting your schedule. That’s why a lot of people just wouldn’t have experimented with it.”

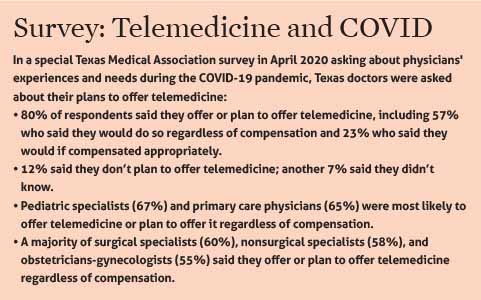

Nora Belcher, executive director of the Texas e-Health Alliance, a telemedicine vendor group, says collecting data on the COVID-driven expansion of telemedicine, and showing that it works, will be key to making the case for increasing telemedicine’s role post-pandemic. She says telemedicine has suffered from a “chicken-and-egg problem”: Policymakers want to see that it works before signing off on it, but convincing them of that requires allowing its use first.

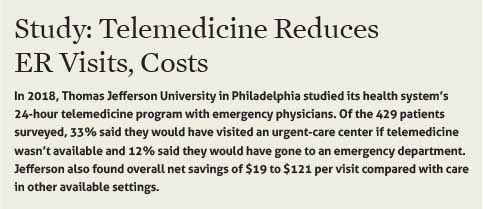

“If this is perceived as only increasing utilization, and not doing things like bringing down unnecessary ER visits and other things, these conversations become much, much harder,” Ms. Belcher said. “It’s very black-and-white right now: We have to do social distancing. In the long term, assuming that we don’t live in social distancing forever, this is a great opportunity to get data capture that shows the cost effectiveness and the efficacy of telemedicine in these places that we haven’t been doing it before.” (See “Study: Telemedicine Reduces ER Visits/Costs,” page 18.)

When the Texas Legislature convenes in 2021, TMA plans to push for permanent payment parity similar to what the state mandated in its emergency rules. TMA also plans to advocate for making permanent the temporary regulatory changes that have allowed telemedicine to expand during the pandemic.

TMA Vice President for Advocacy Dan Finch says telemedicine should be viewed as “a rather ubiquitous means of providing a covered service.” As long as a contracted physician performs a covered service that meets with the standard of care, what an insurer pays for that service shouldn’t depend on how it’s provided, he says.

“This is the toothpaste we don’t want to put back in the tube. We don’t want to go back to the old way of doing business,” Mr. Finch said. “If folks are getting comfortable with this as a means of providing the service, it needs to be paid for appropriately.”

The Texas Association of Health Plans acknowledged an interview request from Texas Medicine but did not provide comment by press time.

The physicians who dove into telemedicine for COVID-19 have a generally positive but measured view of its future, often saying its viability depends on the specialty or type of visit.

Dr. Kaplan notes behavioral health is a big part of general pediatrics today, and “I can totally see continuing to do much of the developmental, behavioral, and mental health stuff by telemedicine.”

Without lasting changes, Dr. Chemitiganti at Texas Tech doesn’t foresee a grand shift in the use of telemedicine once the pandemic subsides. He’s heard skepticism from physicians over the years, particularly those in private practice. He says their perspective changed recently only because of the circumstances the pandemic created.

“I want to be optimistic and say probably a year after this pandemic has ended, maybe about a quarter of our practices will still maintain a viable telemedicine kind of an option, especially for chronic disease management,” he said. “But the rest might [act] based on what CMS is going to do. If the billing and coding doesn’t work, then doctors throughout the state of Texas and elsewhere, to keep their practice going, they might need to switch back to conventional medicine.”

Dr. Valenti believes payment parity should become permanent.

“If you’re giving the same amount of clinical problem-solving to the issue that you would otherwise give, and giving the same or more time to the patient that you otherwise would give, then those are two of the biggest components of how visits are valued,” he said. “If you want to decrease your emergency room [visits], funding telehealth and parity makes sense.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(7):14-19

July 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page