It’s Going to Hurt All of Us

In a rural Texas town where one-third of the patients admitted to the local hospital have no insurance, Athens family physician Douglas Curran, MD, does all he can to keep women like Rose (not her real name) out of the hospital.

In a rural Texas town where one-third of the patients admitted to the local hospital have no insurance, Athens family physician Douglas Curran, MD, does all he can to keep women like Rose (not her real name) out of the hospital.

Rose is part of what Dr. Curran calls “this massive group of working poor who have no access to care.” She doesn’t make enough to afford private insurance. She makes too much to qualify for Medicaid.

“She’s one of the strategic breadwinners in the family,” he said. “So when she’s not working, they’re struggling just to buy food.”

Rose just can’t afford to get sick, says Dr. Curran. And Texas can’t afford for Rose to get sick either. Not Rose and not the men and women who tend our ranches, build our office towers and highways, or serve our meals — the 4.5 million Texans who put our state at the top of the nation’s list of uninsured residents.

“Right now, we have a state that’s really moving business-wise, a lot of things are happening,” he said. “If you keep people healthy, they’re producing, they’re generating, they’re keeping things going. But if that populace is not properly cared for and supported and empowered, then we’ll see the people that we really need to keep our business environment pristine begin to drift away. It’s going to hurt all of us.”

Dr. Curran was on call the night Rose was wheeled into the emergency room. She was short of breath, had “big swollen feet,” and the oxygen level in her blood was dangerously low. He drained 50 pounds of fluid from her body and released her on aspirin and three generic medications — “three, $4 drugs” — to treat her congestive heart failure and high blood pressure.

Thankfully, Dr. Curran also was able to refer Rose for follow-up to a local, physician-run, volunteer clinic for the working poor.

“We take care of the people who can pay a little bit there,” he said. “They pay $15. It goes into the pot to keep the clinic going. The nurses are all volunteers. My wife’s an RN; she volunteers there a day a week. You do what you have to do.”

At the clinic, doctors and nurses can check Rose regularly to make sure the medicines are keeping her healthy — and to make sure the drugs’ side effects aren’t making her sicker. Without those check-ups, neither Dr. Curran nor any other physician could safely refill her prescriptions. Nor would they.

“Nobody’s going to refill those medicines, so she’ll re-accumulate that fluid, and she’ll be back in the hospital, and it costs $25,000 to get her back to a stable state on those $4 medications,” he said. “At the end of the day, that raises your insurance rates, my insurance rates, and everybody else’s insurance rates because she’s back in the highest cost place to get care there is (the emergency department).”

After passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, 33 states expanded eligibility for their Medicaid programs to include people like Rose. Texas did not, and all of the state’s top leaders remain strongly opposed to expansion.

Dr. Curran supports finding ways to get more Texans insured, but he says his practice can’t afford to accept too many Medicaid patients. With operating costs of $41,000 a day for 17 family physicians and Texas’ notoriously low payment rates for primary care services, Medicaid is a losing proposition.

“It’s not enough to pay my bills or to keep the lights on and to pay my employees,” he said. “A visit for a sore throat pays me about $27, and it costs me about $48 to see the patient in my office. I’d be better off [financially] giving a Medicaid patient 10 bucks and sending her to the emergency room.”

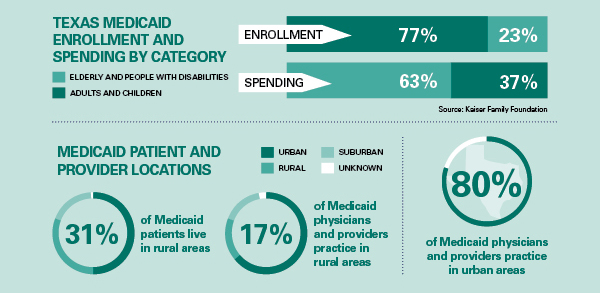

For more than a decade, Texas has held the title of “Uninsured Capital of the United States.” And for the first time in a decade, the number of children without health insurance increased in 2017, eroding Texas’ slow gains in coverage for children. The friction created when 17 percent of the population lacks health insurance threatens to slow our booming Texas economy. It increases costs to taxpayers and insured Texans, and heaps unpaid expenses onto physician practices and hospitals. It leaves 4.5 million uninsured men, women, and children wondering what they’ll do if they become seriously ill or injured. Meanwhile, Medicaid, CHIP, HTW, and other safety net programs struggle to meet their mandates. Terribly low payment rates, incessant bureaucratic hassles (for physicians and patients), and a confusing maze of not-well-connected delivery systems are primarily to blame. Patients end up seeking far too much primary care and routine care in emergency departments, the most expensive piece of our health care system. TMA’s prescription to enhance access to health care includes innovative coverage models for the working poor, competitive Medicaid payment rates, a revolution of simplicity and transparency for all of the state’s health programs, further investments in cost-effective ways to grow our physician workforce, and more progress on telemedicine.

Strengthen Medicaid

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage for nearly 4 million Texans — two-thirds of them children. About two-thirds of Texas Medicaid spending, however, pays for care for adults with disabilities and seniors. The state contracts responsibility for nearly all of the program to managed care organizations (MCOs). Recent news reports have revealed extensive problems with some of the MCOs’ management of care for extremely vulnerable patients. For physicians, Medicaid and CHIP are typically the lowest payers. They often do not cover the basic cost of providing care. Furthermore, Medicaid’s mounds of paperwork saddle practices with extra costs without benefitting patient care. As a result, the Medicaid physician network has shriveled dramatically, harming patient care and contributing to higher costs for taxpayers. Physicians, hospitals, and MCOs have begun a collaboration to identify reforms that promise to improve patient care while decreasing Medicaid-related headaches and hassles.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Allocate funds to ensure competitive and appropriate Medicaid payments, prevent Medicaid payment rate cuts, and promote fair payment to match inflation and cost of practice increases.

- Reduce administrative burdens and bureaucracy surrounding physician participation in Medicaid and all other health benefit programs, reduce unnecessary prior authorization requirements, and integrate Medicaid and managed care enrollment and credentialing.

- Increase HHSC oversight, transparency, and accountability for Medicaid MCOs, including improved monitoring of MCO network adequacy.

- Support innovative Medicaid MCO/physician collaborations that reduce red tape and reward high-performing practices.

Continue to Expand Graduate Medical Education

Texas has led the nation in population growth for the past two decades, adding nearly half-a-million people a year over that time. All of these new Texans need a lot more doctors. The state currently has 12 medical schools — three of which opened since 2016 and have yet to produce a graduating class. Three more are scheduled to open by 2021. The annual number of graduating physicians will grow from about 1,800 in 2019, to more than 2,200 by 2024. But becoming a physician is a two-part process: four years of medical school, followed by three or more years in residency, or graduate medical education (GME). Texas retains 80 percent of physicians who complete medical school and residency in Texas, but a much smaller share of those who go out of state for GME (after Texas taxpayers spent about $180,000 each to support their medical education). Thanks to strong, continued support from the Texas Legislature, the state has engaged in a steady expansion in the number of GME slots available. In 2018, Texas finally reached its goal of having 1.1 GME positions for every medical school graduate. A much larger investment will be needed to keep up with all the new medical schools and to keep as many new doctors in Texas as possible.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Fully fund GME to maintain the ratio of 1.1 entry-level residency positions for every Texas medical school graduate.

Improve Access to Care in Rural Areas

Texas’ physician shortage is particularly acute in our state’s vast rural areas. Of Texas’ 172 rural counties, 101 are designated as “Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas.” Eighty-four rural Texas counties have five or fewer physicians; 24 counties have none. Ten rural Texas hospitals have closed permanently since the beginning of 2013.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Restore funding for the primary care Physician Education Loan Repayment Program and the Family Medicine Residency Program.

- Support the development of rural health GME tracks to produce more physicians for rural Texas.

- Provide other incentives for physicians to practice in rural and underserved areas, especially in primary care and other needed specialties.

Boost Telemedicine Access and Payment

The 2017 Texas Legislature made tremendous progress, passing a law that defines telemedicine as a way to deliver health care, not a health care service. It also clarifies that the standard of care for a telemedicine visit is the same as when a physician sees a patient in person. With that framework in place, the state can now take steps to take better advantage of this technology.

TMA recommends that the Texas Legislature:

- Improve broadband access across Texas to accelerate telemedicine adoption and implementation.

- Support innovative uses and applications of telemedicine to promote continuity of care across all specialties.

- Require health plans to allow a patient’s physician to utilize — and get paid for utilizing — telemedicine to provide a covered service, through a platform of the physician’s choice.

- Ensure that patients’ regular physicians can use telemedicine to treat their patients and not force them to go to an outside vendor for telemedicine services.