Like everyone else, LGBTQ patients can face some unusual medical problems, says Kelly Bennett, MD, a Lubbock family physician who focuses on helping Texas’ LGBTQ population. But many of these patients’ biggest challenge is that their health problems can be amplified by hostility from others.

Case in point:

“I was on hospital service last week, and a trans[gender] woman whose father does not approve took an overdose in [a Houston suburb],” said Dr. Bennett, associate professor of family medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. “The father tossed the kid in the car, drove [about 485 miles] to Lubbock and dumped the kid in our emergency room and then left the country. That’s the level of lack of support that some of our patients have.”

In this instance, the lack of support may have actually worked in the patient’s favor. Dr. Bennett, who is lesbian, and two other physicians present were trained to work with transgender patients. When the patient arrived, she was “practically mute” when asked about her attempt at suicide. But because the physicians were ready and willing to help, they were able to assist in her recovery.

“I cannot even express to you the 180-degree turn in this person’s mood, and [her feeling] that maybe there was hope for a future,” Dr. Bennett said.

In 2017, about 3.6% of Texans identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, compared with 4.5% nationwide, according to the Gallup daily tracking poll. Nationally, that is up from 3.5% when Gallup began asking that question in 2012.

Those numbers may be higher because young people are more willing to identify as LGBTQ, Gallup says. The increase in identification from 2012 to 2017 was driven almost entirely by “millennials” – those born between 1980 and 1996 – who are more likely than any other age group to identify as LGBTQ, the polling agency says.

All LGBTQ groups – especially transgender people – see a disproportionate number of health problems, says M. Brett Cooper, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. That is borne out by a report from the Healthy People 2020 initiative by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It found that groups within the LGBTQ population face high rates of mental illness, HIV, obesity, suicide, and homelessness, among other health problems. They also have some of the highest rates of tobacco, alcohol, and drug use.

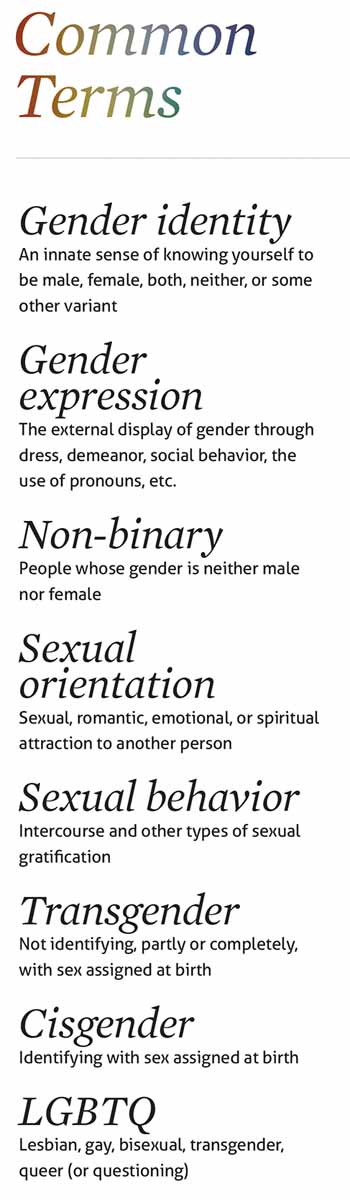

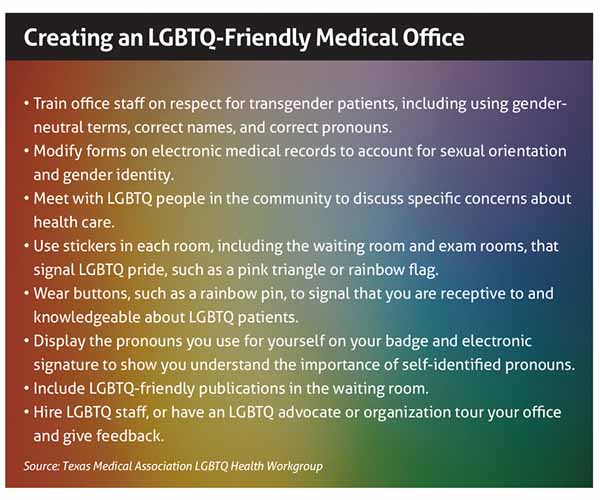

Meanwhile, structural problems within the health care system frequently discourage LGBTQ patients from visiting physicians. For instance, the questions and forms on electronic medical records usually assume heterosexual and cisgender patients. Also, many physicians and their staffs remain ignorant about the correct use of names and pronouns with transgender patients.

Prejudice also plays a role, says Dr. Bennet, who is a member of the Texas Medical Association’s LGBTQ Health Workgroup, which has developed resources and CME to help physicians improve treatment for LGBTQ patients. (See “TMA’s LGBTQ Resources,” below.)

LGBTQ patients frequently avoid physicians because of previous bad experiences or because they are afraid the secret of their sexual identity will come out. This, in turn, leads to health problems that fester until they become a crisis, she says.

Many physicians who would like to treat LGBTQ patients often hesitate because they fear they lack the training, says Dr. Cooper. While it’s important for physicians to educate themselves on treating LGBTQ patients, it’s equally important for those patients to have better access to care.

“The big thing is just encouraging physicians that these youth and adults are no different than anyone else in your practice,” Dr. Cooper said.

Better preparation

Better preparation

Physicians’ lack of awareness about LGBTQ health begins with medical schools. The exact number of medical schools teaching about LGBTQ health is unclear, but a 2011 survey of 132 U.S. medical school deans found that on average only five hours of training are spent on the subject, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

While some schools have improved their LGBTQ training since then, there is little evidence that most physicians are adequately prepared. A 2018 survey of 658 New England medical students found that 80% of respondents felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” with the treatment of “gender and sexual minority patients.” Meanwhile, the 2012 National Transgender Discrimination Survey found that 50% of transgender respondents said they had to teach their physician about transgender care.

Of the six measures spelled out in Healthy People 2020 to improve LGBTQ health, two involved physicians. One called for better medical school education, and the other called for physicians to be “supportive of a patient’s sexual orientation and gender identity to enhance the patient-provider interaction and regular use of care.”

Dr. Bennett says she frequently receives referrals from other physicians who don’t wish to work with LGBTQ patients. Also, she hears stories from LGBTQ patients about being treated poorly by physicians. For instance, some physicians refuse to touch patients, while others are rough and abusive. Still others refuse to write certain types of prescriptions.

“I don’t know how many men have come in to see me after they’ve gone to their own health care provider in Lubbock or some other primary care doctor, and have been told literally, ‘You want PrEP [a drug that prevents HIV infection]? I’m not going to help you live that kind of lifestyle,’” she said.

While discrimination is a problem, the bigger obstacle to care is that most physicians simply aren’t familiar with the types of treatment or screening LGBTQ patients need, says Wesley Hartman, a lawyer who specializes in LGBTQ health issues for the Austin Medical-Legal Partnership, a collaboration between Austin’s People’s Community Clinic and Texas Legal Services. For instance, if an otherwise friendly physician does not offer needed treatments like hormone-replacement therapy, “that probably isn’t the most useful resource,” he said.

Common problems

Health issues for LGBTQ patients can change depending upon their age. LGBTQ adolescents are much more likely than other adolescents or older LGBTQ patients to need mental health services, Dr. Cooper says.

“To be very honest, there’s nothing else really different about [LGBTQ adolescents],” he said. “It’s just that they’re dealing with a lot more bullying, and the mental health thing is really big. But they’re still having sex [as much as] their straight counterparts.”

Older LGBTQ patients are at high risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Gay men – especially African American gay men – have the highest rates of HIV, syphilis, and other STIs. Meanwhile, lesbians are more at risk for breast and ovarian cancer because they often don’t get pregnant, which modifies the chances of contracting those cancers.

“There’s also more smoking, drinking, and drugs [among all LGBTQ patients] because people who are disenfranchised have reason to take solace in all those things,” Dr. Bennett said.

High rates of STIs and drug use feed into negative stereotypes about LGBTQ patients, but those rates are more of a reflection on the difficulty of obtaining health care than on the patients themselves, Dr. Bennett says.

“They haven’t felt comfortable going to a doctor,” she said.

As a result, many adult LGBTQ patients hold off on seeing physicians until their health deteriorates. By the time they show up in Dr. Bennett’s office, they often need to be referred to specialists for diabetes or cancer. That leads to other problems since finding specialists who are sensitive to the needs of LGBTQ patients can be difficult, she says.

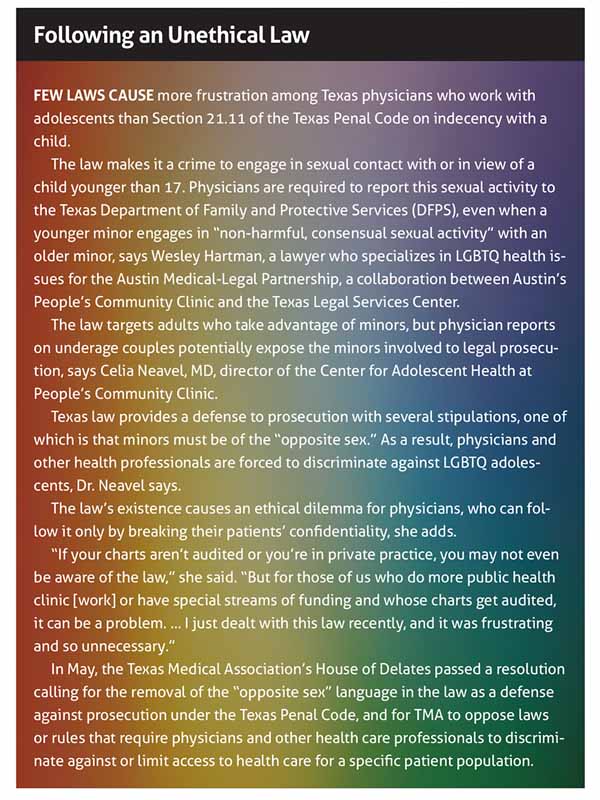

LGBTQ patients also have legal and social issues stacked against them. (See “Following an Unethical Law,” page 25.) And they are the most at risk for unemployment, lack of access to health insurance, and homelessness, Hartman says.

“All of these factors can have a huge impact on the patient’s health and their ability to access health care and comply with treatment plans,” Hartman said.

Dr. Bennett says transgender patients as a group face more prejudice than lesbian, gay, or bisexual patients. This makes some transgender patients understandably defensive, she says. Recently, a transgender patient got angry at one of her staff people, accusing him of homophobia. The staff person was himself a gay man.

“I can guarantee you there was no homophobia going on there,” she said. “But a lifetime of discrimination caused her to be incredibly sensitive.”

Even well-intentioned physicians may offend transgender patients who’ve had a previous bad experience, says Emily Briggs, MD, a family medicine specialist in New Braunfels and a member of the LGBTQ Health Workgroup.

“If I walk in the room and say something that brings up that previous experience, they may be shut down to me, and it takes me months of visits, if they’re willing to keep coming in, to reopen those doors.” Dr. Briggs said. “At times, it’s like dealing with somebody who has had abuse.”

If that happens, she says, it’s important to “stay communicative and to keep that dialogue open, especially as the person perceived as holding the power in the room.”

Even physicians who are experienced with LGBTQ patients can accidentally offend at times, says Dr. Cooper. Using the wrong name or pronoun for transgender patients is a common error, but recovering from it also is easy.

Physicians should start every exam by introducing themselves and asking, “Do you prefer to be called by” whatever name is on the chart, Dr. Cooper says. If the patient turns out to be transgender and wants to use another name or other pronouns, then make sure that’s what you and your staff use in the future.

“When we do make a mistake – just like we would for anything else in medicine – promptly apologize to the patient and try to do the best that you can,” he said. “I think that’s all they ask of us – that they know that you’re affirming and you want to try.”

Tex Med. 2019;115(9):20-25

September 2019 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page