Think Congress never gets anything done? Well, Texas Medical Association President David C. Fleeger, MD, has a warning for you:

Make yourself heard right now, or Congress actually might do something and surprise you with legislation that could give health plans an unfair advantage in out-of-network billing disputes.

The widespread call to severely curb or end “surprise” medical bills prompted competing federal legislation during the summer and fall of 2019. The negotiations, maneuvering, and bill markups have continued into this year. Similar to a new Texas law governing state-regulated plans, federal proposals would ban balance billing and remove patients from having any role in out-of-network payment disputes.

But with insurer-friendly language lurking in many of those proposals, Dr. Fleeger warns the impact of such legislation could go well beyond out-of-network payment.

“This isn’t just about doctors that balance bill. This is about all doctors and what they get paid by insurance companies,” said Dr. Fleeger, an Austin colon and rectal surgeon. “And if doctors don’t stand up and make sure that Congress understands that what we need is a system in place that allows us to make sure we have a plan to play fair, then [Congress is] essentially fixing our rates and driving another nail in the casket of private practice.”

At stake in this Washington, D.C., wrangling: How much physicians get paid for the vast majority of out-of-network care in the nation. In Texas specifically, federal legislation would cover out-of-network billing disputes involving plans not regulated by the new state law. (See “The Texas Arbitration Law,” page 20.)

TMA and the American Medical Association want a system with balance, including an independent dispute resolution (IDR) process and a fair benchmarking system to help determine appropriate physician payments. Health plans are committed to either stopping IDR from becoming part of the federal framework or limiting it to medical bills above a certain amount. They’re also backing proposed benchmarks set solely by insurers – an approach TMA believes would line health plans’ pockets while leaving physicians underpaid, out of network, and perhaps out of patience with their profession.

What medicine requires

Since Congress’ look at so-called surprise bills heated up during 2019, TMA has maintained that any federal legislation should:

- Take patients “out of the middle” of out-of-network surprise billing disputes between insurers and physicians, hospitals, and practitioners;

- Require a fair initial payment from the health plan to the physician;

- Use an IDR process that doesn’t give an unfair advantage to either side;

- Use a benchmark identified by market forces via an independent, not-for-profit database to determine fair compensation in the IDR process;

- Base final payment on clear factors, including the complexity of the case and the experience of the physician; and

- Incentivize health plans to offer measurably adequate networks of physicians, hospitals, and other practitioners.

For state-regulated health plans in Texas, a process that features much of that wish list is already in effect. State Rep. Tom Oliverson, MD (R-Cypress), believes Texas was the catalyst for the federal action that began unfolding in 2019 and an example of what Washington can achieve.

Lawmakers in D.C. “correctly read the tea leaves that if in a conservative state like Texas, we could pass a fairly balanced, fairly middle-of-the-road approach that incorporated IDR with some meaningful benchmarks that ensured that there would always be a strong incentive to keep your networks adequate, and negotiate fairly with providers,” then there was hope to do it on a federal scale, Representative Oliverson said.

And that scale is a big one. The Texas Department of Insurance says Senate Bill 1264 applies to plans covering about 16% of Texans. Federal legislation would cover the rest of Texas’ insured – and would be, in the words of Austin oncologist Debra Patt, MD, “transformative.”

IDR: The New York balance

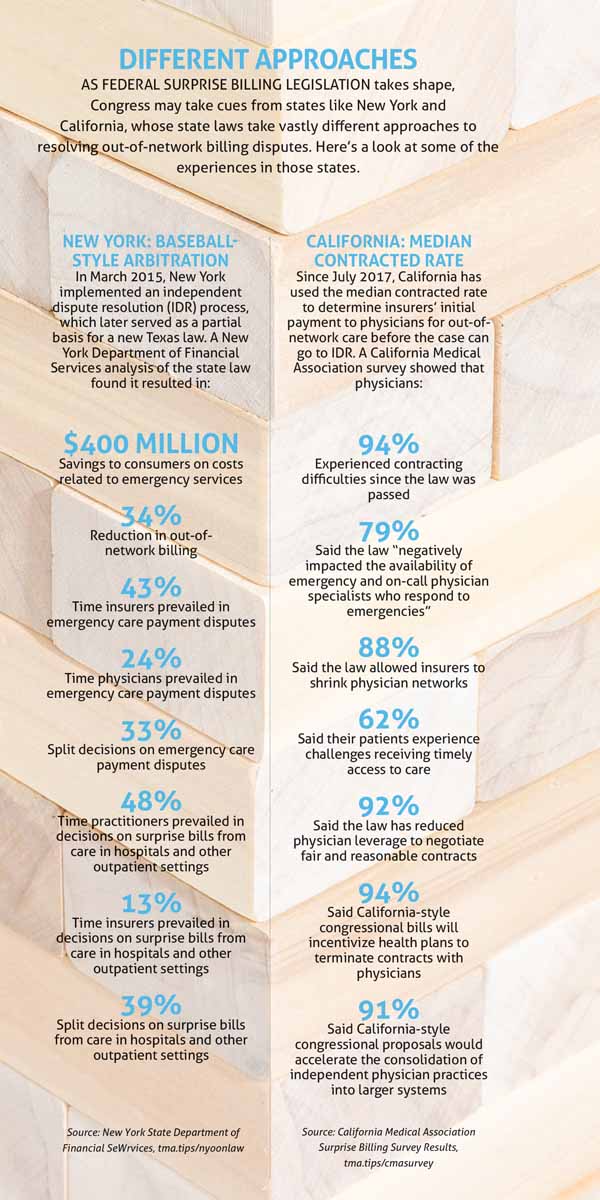

Because the Texas law is so new, there aren’t yet statistics and anecdotes to chew on. But New York’s system – which Representative Oliverson lauds for “actually allowing free markets to work” – has netted encouraging results.

In the New York model, which took effect in 2015, an arbitrator decides whether “the provider’s fee or the health plan’s payment is more reasonable, based upon the last best offer of each party,” the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) noted in its report examining the performance of the out-of-network law in its first few years. Arbitrators must use the 80th percentile of billed charges − calculated by independent benchmarking organization FAIR Health − as a reference point to determine the physician’s payment. (SB 1264 included that 80th percentile figure as one of the 10 factors that Texas arbitrators must consider, and Texas also uses FAIR Health to determine that benchmark.)

Moe Auster is senior vice president and chief legislative counsel of the Medical Society of the State of New York, which supported the state law. He says the goal included making sure physicians would be available for on-call care in emergency departments, and that health insurers have sufficient networks to serve patients.

There’s “recognition that it’s a fair process – that there’s a balancing of the interests … on the part of the physician to take a little less than what their billed charge might be, and there’s a balancing of the interest on the part of the health insurer that they need to be fair in dealing with physicians,” Mr. Auster said.

DFS’ analysis of the New York law called it “a true success.” The department found that between its March 2015 implementation and the end of 2018, the IDR law had saved consumers more than $400 million in costs associated with emergency services, “in part through a reduction in costs associated with emergency services and an increased incentive for network participation.” The law also reduced out-of-network billing by 34%. (See “Different Approaches,” right.)

Westchester, N.Y., plastic surgeon Andrew Kleinman, MD, who helped write the New York law, says it has worked “truly, amazingly well.” Back when he was on emergency call more than he is now, he’d use the IDR process to good effect; he says New York’s version of the system allowed him to negotiate fairer payments.

“A lot of times, the insurance company would make me an offer of the in-network rate, and I would say, ‘No, and if that’s what you pay me, fine. Go ahead and pay me that, and then we’ll go to the IDR.’ At which point, they would always make me an offer of something that was reasonable,” Dr. Kleinman said.

TMA wants to see federal legislation modeled after New York’s as it watches to see if Texas’ own system will work as intended.

“They’ve been very balanced. … And I think at the end of the day, that’s really what we want,” Representative Oliverson said. “What we really want is a solution to this problem to where nobody can point the finger at health care providers anymore and say, ‘You guys are greedy, and you’re part of the problem.’ That’s what the independent dispute resolution does.”

Trouble in Congress

Proposals in Congress, though, have Texas physicians concerned about creating a system in which doctors are paid based on an insurer-friendly yardstick and would have little if any recourse to dispute those payments.

In December 2019, it appeared as though medicine might suffer a troubling defeat when three leading lawmakers announced what they called a “compromise” measure. A new version of the Lower Health Care Costs Act, sponsored by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Reps. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) and Greg Walden (D-Ore.), would have used insurers’ median in-network rate as the benchmark to determine what physicians are paid. It would have offered an arbitration process only if the median in-network rate is greater than $750.

Physicians breathed a sigh of relief when that measure didn’t pass as part of a year-end funding package. But its most basic planks – such as the median-in-network benchmark – are serious red flags for TMA as the debate continues.

“If physician payment was at [the median in-network rate], then that would be a race to the bottom,” said Dr. Patt, chair of TMA’s Council on Legislation. “No payer would ever contract with physicians or physician groups, because it would always be a cheaper alternative to undergo dispute resolution.”

TMA has warned federal lawmakers about the impact of California’s out-of-network billing law, which uses the median in-network rate for initial payment. The Golden State’s physicians have reported significant contracting difficulties, reduced negotiating power, and other problems. (See “Different Approaches,” page 19.)

Representative Oliverson is similarly concerned about a scenario in which insurers would never have to pay more than the average of what they were already paying.

“It creates a perverse incentive to actually remove contracted physicians from their contracted networks and place them in an out-of-network situation,” Representative Oliverson added. “It will end up creating a race to the bottom. … It will result in provider shortages. It will have a devastating effect on rural health care, as rural hospitals find it more difficult to pay their bills and to compete and stay open in the marketplace when the best they can get is the average. It also doesn’t incentivize quality.”

The insurers’ perspective

Despite New York’s plaudits for its out-of-network law, health insurance companies actually cite the New York experience as an example of why they oppose arbitration.

Clare Krusing, a spokesperson for the Coalition Against Surprise Medical Billing, says New York’s system leads to higher costs. The coalition’s membership includes America’s Health Insurance Plans, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and the American Benefits Council. A coalition statement says the group aims to “avoid a costly, bureaucratic arbitration process” that would lead to hikes on both premiums and costs to taxpayers.

New York’s system “has largely been taken advantage of in terms of certain specialists, certain providers being repeat offenders, sending bills to arbitration that ultimately are disproportionately decided in the favor of the provider, and ultimately lead to much higher costs for patients and for employers,” Ms. Krusing told Texas Medicine. “All of those costs continue to eat away at the very type of financing, both for individuals personally, but also take up an exorbitant amount of health care spending for the country.”

She cited an examination of the New York DFS report by the Brookings Institution in October 2019. It found the state’s data “suggest that the state’s arbitration process is substantially increasing what New Yorkers pay for health care.” With arbitration decisions averaging 8% higher than the 80th percentile of charges, the report called the benchmark “clearly inflationary guidance. … Therefore, it is likely that the very high out-of-network reimbursement now attainable through arbitration will increase emergency and ancillary physician leverage in negotiations with commercial insurers, leading either to providers dropping out of networks to obtain this higher payment, extracting higher in-network payment rates, or some combination thereof, which in turn would increase premiums.”

Ms. Krusing denies that setting a benchmark at the median in-network rate incentivizes health plans to kick physicians out of their networks.

“It runs against what plans have to do with their own networks. They have to meet network standards that include the number of providers [and] types of specialties,” she said. “For them to be competitive in offering the right type of networks to attract consumers, they’re going to have to negotiate with the best doctors to have those folks in their network regardless.”

She says while the coalition supports a benchmark approach as a key method of addressing surprise bills, its members have differences of opinion on what those gauges should be.

“I will say one of the important considerations that we have is that the benchmark is reflective of the rate in the market,” she said. “It’s not setting one uniform price or reimbursement for [emergency] care across the country. It’s making sure that the rates do reflect the cost of providing care in those markets so that providers are paid a fair and reasonable amount.”

The New York Health Plan Association is more positive about the state’s out-of-network law. In October 2019, the association urged New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to sign legislation expanding its patient protections.

“The current independent dispute resolution process has worked well, ensuring that reimbursements for emergency services are fair and reasonable while holding individuals harmless,” the association said in its October release.

Important for all docs

At press time, lawmakers had introduced new federal proposals to address surprise bills, including the Consumer Protections Against Surprise Medical Bills Act. That measure is cosponsored by a Texas lawmaker, Rep. Kevin Brady (R-The Woodlands), ranking member of the House Ways & Means Committee, and the committee’s chair, Rep. Richard Neal (R-Mass.).

The Brady-Neal measure, as proposed, would introduce a 30-day negotiation process between physicians and health plans over bill disputes; an IDR process then would become available if no agreement is reached in the negotiations. The bill contains no minimum dollar threshold for disputed bills to go to IDR.

TMA will continue to monitor developments with that bill and other federal surprise-billing proposals.

Meanwhile, Dr. Fleeger, TMA’s president, emphasizes how important the surprise-billing debate is, and how far-reaching a legislative misstep on out-of-network payments could be. A baseball-style arbitration system, he says, makes the bad actors on both sides – physicians who might exorbitantly bill and bad-behaving insurance companies – come to the middle with a more reasonable offer.

But the wrong payment standard, he warns, strips physicians of their negotiating power.

“The ultimate concern that all of our doctors need to have is that if that happens,” Dr. Fleeger said, “then the bell curve, which is the curve of which all doctors – not just balance-billing doctors, but all doctors – are getting paid, shifts to the left. In other words, the average becomes a lower number over and over again, year after year, because there are fewer and fewer people on the right side of the bell curve, getting paid above average. Because insurance companies have no [incentive] to keep them there. And that ultimately leads to all doctors getting paid less.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(3):16-21

March 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page