On Feb. 21, 2017, the medical staff and patients at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston got a pretty big scare. Reports of a man who said he had a gun and planned to use it forced the hospital into emergency procedures that led to a tense two-hour lockdown.

Turns out, it was a false alarm. But Ben Taub staff weren’t taking any chances, having already experienced a murder-suicide in which two died in 2014.

“We must have had 50 cops there in 10 minutes,” Ben Taub Chief of Staff and Surgeon-in-Chief Kenneth Mattox, MD, said of the 2017 incident. “They flooded the hospital and found the guy who did the talking. And they took him to the clinic where people had overheard him [talking about shooting], and they found out he had no gun.”

The FBI defines an active shooter as “an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area.” Mass shootings tend to get the most attention, yet they have no set definition. A 2013 federal law defined “mass killing” as an incident in which three or more people are murdered in a public place, usually in a single location.

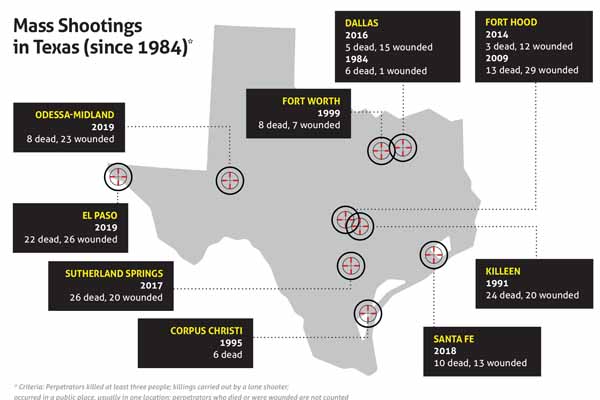

Texas hospitals have responded to several mass shootings in recent years. (See “Mass Shootings in Texas,” page 38.) Fortunately, no Texas hospital or clinic has been the site of a mass shooting so far. Nationally, however, those types of shootings have occurred at hospitals, medical clinics, nursing homes, and a nursing school. In January, the Texas Medical Association outlined eight recommendations for addressing mass violence at a hearing of the Texas House of Representatives’ newly created Select Committee on Mass Violence Prevention and Community Safety (www.texmed.org/MassViolenceStrategies).

“There have certainly been shootings at hospitals in Texas … but we’re frankly lucky that [a mass shooting] hasn’t happened yet,” said Alexander Eastman, MD, a Dallas trauma surgeon who also is a lieutenant in and chief medical officer for the Dallas Police Department. “Most hospitals are what we’d consider soft targets with open access and varying levels of physical and personal security, depending on the institution.”

Medical staffs prepare for all kinds of emergencies, but a mass shooting is different from other types of disasters, Dr. Eastman says. While a fire or a storm can be dangerous, they’re not deliberately hunting down people. That means the staff’s preparations for and reaction to a shooting event are different as well.

“[If] this happens in your institution, it’s going to be like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” he said.

Ethical complications

Texas is forever tied to mass shootings because on Aug. 1, 1966, Charles Whitman killed two family members and then used the tower at The University of Texas at Austin as a vantage point to kill another 15 and wound 31. Since then, mass shootings have become far more frequent and more deadly, according to a study by The Washington Post (tma.tips/WPShootingReport).

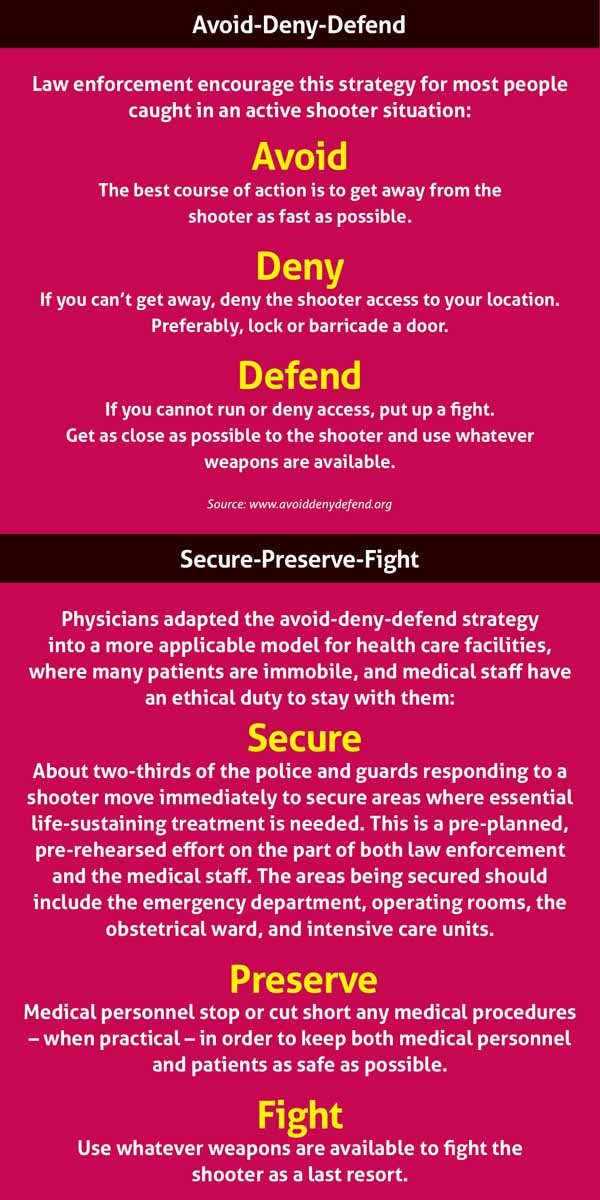

Law enforcement agencies have come up with a protection strategy known as “avoid-deny-defend.” (See “Avoid-Deny-Defend,” right.)

However, physicians and other health care workers have pointed out the ethical difficulties that strategy presents for them. Regardless of the danger involved, medical workers are highly reluctant to avoid a shooter if it means abandoning patients who are undergoing surgery, delivering a baby, or otherwise immobile, said Pete Blair, PhD, executive director of the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) Center at Texas State University in San Marcos. He teaches this strategy in active shooter trainings, like the one he presented at TMA’s annual meeting in 2017.

“In that case, you should get better at denying [the shooter] access to your people, which would mean having doors that are closeable, lockable, barricade-able,” Dr. Blair said. “Also thinking more about how you defend those people, if it comes to that. In some hostile environments, that can mean you have armed security or something like that. Or it can mean you’re just talking to your staff and your physicians about what options are available to defend yourself.”

During Ben Taub Hospital’s shooting scare, staff members came to a similar conclusion. In carrying out their training under the avoid-deny-defend strategy, they found that they were potentially threatening the patients, Dr. Mattox says.

“[Medical staff] were hiding as part of the run-hide-fight philosophy when suddenly we realized we were shutting down heart surgery and deliveries,” he said. “That’s when we realized we’ve got to have a better plan.”

The new plan was spelled out in an Aug. 9, 2018, New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) article, whose coauthors included Drs. Eastman and Mattox. It calls on medical facilities to employ a strategy they called “secure-preserve-fight.” (See “Secure-Preserve-Fight,” page 37.)

The authors noted that police tend to show up almost immediately in response to shooter events. Also, hospitals tend to have armed guards and law enforcement around. In the past, these officers would normally begin chasing down the shooter.

The “secure-preserve-fight” strategy would direct about two-thirds of the police and guards to securing key parts of the facility, according to the NEJM article. Their job would be to protect vulnerable patients and the medical staff needed to care for them.

Avoid-deny-defend is an excellent strategy for most people caught in an active shooter situation, and it needs to be widely taught, Dr. Eastman says. In fact, many people in a hospital – visitors, patients, nonmedical staff, and others – should probably follow it during a shooting situation, he says.

“But secure-preserve-fight is a much more applicable model for health care use,” he said.

Making it real

“You can’t look at a location and say, ‘It just doesn’t happen there,’” Dr. Blair told Texas Medicine. Hospital shootings are rare, “but it is worth spending some time thinking about it because when it does happen it’s a life-threatening event,” he said.

Hospitals and other medical facilities drill for all kinds of disasters, including active shooters. When they do, they need to simulate the real situation as much as possible so that they can anticipate the unique problems involved, says Alan Tyroch, MD, chair of surgery at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center El Paso and chief of surgery and trauma medical director at University Medical Center El Paso. Dr. Tyroch coordinated the care for victims in the Aug. 3, 2019, El Paso Walmart shooting.

“If you do halfway disaster training, you’re not going to be prepared,” he said.

Though there are no statistics or studies on the subject, many Texas hospitals probably are not as prepared as they should be for a shooter event, Dr. Eastman says. Most facilities announce their drills well in advance and hold them during regular work hours, Dr. Eastman says. That kind of exercise will not prepare staff for the abrupt crisis posed by a real active shooter, he says.

“I came out of my [medical] training in 2001, and I have not seen a surprise night or weekend disaster drill yet,” he said. “You’ve got to be prepared for that.”

Facilities also need to brace themselves for the event’s aftermath, Dr. Tyroch says. The violence typically takes no more than a few minutes, and then police will need time to comb the building to root out other shooters or possible threats. Once that’s done, the facility will still face days and possibly weeks of disruption.

“Things are going to be shutting down because of the event,” Dr. Tyroch said. “Things are going to be frozen.”

More than likely, patients will need to be transferred to other facilities, Dr. Tyroch says. Among other things, hospitals must plan to notify patients’ families about any change in status, and the staff who worked during the shooting will need to be relieved quickly, Drs. Eastman and Mattox wrote with their co-authors.

Both during and after the event, the hospital should keep people informed by making announcements in plain language, Dr. Tyroch says. In the past, hospitals have announced “codes” for different situations, such as “Code Pink” for a suspected kidnapping of a child or “Code Silver” for a possible police action, Dr. Tyroch says. Everyone in the hospital needs to understand what is happening, not just the staff. Because of that need, the Texas Hospital Association endorsed plain language alerts in 2016.

Hospitals also need to be prepared for long-term scars, especially psychological ones, Dr. Mattox said. He and Dr. Eastman advise in their article that it’s important to have a plan for mental care in place, and – since so many people present are likely to scatter quickly – to plan for tracking down people who might have been present.

Tex Med. 2020;116(3):36-39

March 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page