“I don’t think a lot of physicians realize what a huge impact this has and how an undercount of the census can be potentially devastating for our patients,” says Dr. Gambill, an Austin pediatrician who is promoting education about the census through the Texas Pediatric Society and the Texas Educators in Advocacy and Community Health (TEACH) Network, a collaborative of pediatric residency programs.

Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau tries to enumerate each person living in the U.S., and the stakes always are high. The headcount touches virtually every aspect of American life. Among other things, it:

- Shapes the direction of more than $675 billion in federal funding, including programs like Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, SNAP, Title I, special education, Head Start, foster care, school lunches, and childcare programs.

- Shows how seats in the U.S. House of Representatives should be divvied up among the states. Texas’ population growth is expected to give the state up to three new seats in 2020.

- Shows how boundaries for seats in other governmental bodies – like the Texas Legislature – should be redrawn. The legislature itself handles redistricting, so November’s election will determine how those seats – and Texas’ congressional seats – will be changed, says Christine Mojezati, director of TEXPAC.

- Guides local planners about where to build new roads, schools, and public medical facilities.

- Shows businesses, including hospitals and medical practices, where to locate or relocate.

Undercounting remains a common flaw across the country in every census, and this year’s version has the potential for more severe problems than usual, Dr. Gambill says. The two biggest reasons for undercounting are confusion among respondents over who should be counted and fear that the government will use the data for law enforcement purposes, including immigration control, she says.

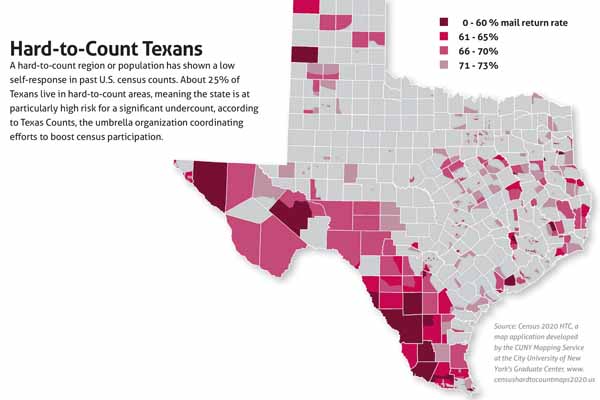

Undercounting is most severe among hard-to-count populations like those in remote rural areas, people who are homeless, low-income communities, immigrants, and people of color, Dr. Gambill says. Children also are more likely to be undercounted. (See “Hard-to-Count Texans,” page 44.)

“The families that are most likely to be undercounted are also the people who will be hurt the most by lost services caused by undercounting,” she said.

Any undercount could cost Texas billions in federal revenue. A George Washington University study examined how a Texas undercount would affect funding for five programs: Medicaid, CHIP, adoption assistance, childcare, and foster care. It found that if Texas’ undercount is just 1% more than the undercount seen in the 2010 census, Texas would lose about $300 billion in those five programs alone. This is a conservative estimate, the study says. (See tma.tips/CensusFundsStudy.)

Because so much is at stake, 45 states have launched state-funded “complete count committees” designed to boost their census counts as much as possible. California is spending $187 million, the most of any state.

But unlike in the census counts in 2000 and 2010, the Texas Legislature opted against any government-financed effort to improve census turnout this year. So coordinating that campaign has fallen to city and county governments and Texas Counts, a coalition of organizations that includes the Texas Pediatric Society, Texas Hospital Association, and Texans Care for Children.

Physicians are trusted members of the community so they’re in a perfect position to talk to reluctant people about the importance of the census, says Carla Laos, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician in Austin who works with Dr. Gambill and others to promote the census. As the daughter of Peruvian immigrants, Dr. Laos says she’s able to bridge language and cultural barriers for many Latino patients.

“As a woman of color, there is value in having someone like me who has become forward-facing and can talk to the community and immigrants and other people who look like me,” she said.

However, all physicians regardless of background or specialty can help improve participation in the census, Dr. Gambill says.

“Just talking about it and creating awareness is important – whether that’s in the media, or writing about it, or talking about it personally with patients,” she said.

Raising the count

Physicians can take several steps to encourage patients to fill out the census that include:

- Reassuring families that the census is safe, especially in immigrant communities. Census workers must take an oath swearing to protect the data they collect for life. Violating that oath can lead to five years in jail and a $250,000 fine, according to the Census Bureau. Also, valid census workers wear a photo identification tag that can be easily checked.

- Stressing the importance of the census. Let patients know that funding for schools, health care, and other vital services hinge on getting an accurate count.

- Guiding patients to materials that can help them overcome language obstacles. Census documents come in English and 12 other languages, according to the Census Bureau. Also, there are language guides and glossaries in 59 non-English languages. (See tma.tips/CensusLanguages.)

- Putting materials that promote the census in waiting and exam rooms. Texans Care for Children, an Austin-based nonprofit has developed several Texas-themed posters, flyers, and other media (txchildren.org/census).

- Providing a dedicated computer for patients to fill out census forms before they leave the clinic. This is especially important for patients with no internet access. Patients also can call the Census Bureau and give their answers or fill out paper forms and mail them in.

Physicians should be on the lookout to let patients and nonpatients alike know that they believe the census is helpful and that responding is important, Dr. Laos says.

“It’s about seizing every opportunity to communicate, educate, and allay fears,” she said.

“Count your babies”

The goal of the U.S. census is to count everyone once where they live, every 10 years, but problems frequently creep into the count. For instance, the 2010 census had a slight overcount of .01% overall, but it undercounted traditionally hard-to-reach populations like African Americans by 2.1% and Hispanics by 1.5%, according to U.S. census data.

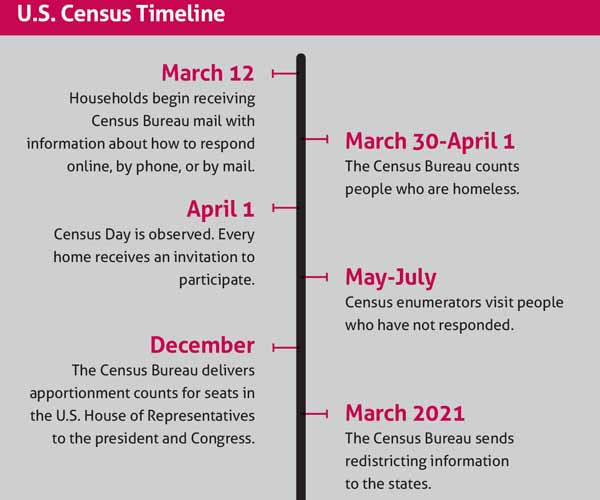

This year’s census has faced federal budget cuts as well as a protracted legal battle over whether to include a question about citizenship for the first time. (The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against it.) The 2020 census also provides the first opportunity for people to respond online, and it’s not clear if all technical issues have been resolved, says Katie Mitten, special projects manager at Texans Care for Children. And about 10% of Americans have no internet access, and that problem is pronounced among blacks, Hispanics, and people who are either low-income or live in rural areas, according to a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center.

These and other difficulties could affect the count. A 2019 report from the Urban Institute found that the 2020 census could undercount the U.S. population by 0.3% to 1.2% – an undercount of 900,000 to 4.1 million people.

As with 2010, African American and Hispanic populations are likely to see some of the biggest undercounts, the report says. Blacks face an expected undercount of 2.4% to 3.7% of their total population, or 1.1 million to 1.7 million people. Hispanics are expected to see an undercount of 2% to 3.6%, or about 1.2 million to 2.2 million people.

Undercounts often reflect mistrust of the census, according to Pew Research. A September 2019 survey by the center found that black and Hispanic adults are more likely than white adults to say they will not respond to the 2020 census.

The chronic undercounting of children has many causes, not all of them obvious, says Tammy Camp, MD, a Lubbock pediatrician and president of the Texas Pediatric Society. For instance, one of the most undercounted groups of children are newborns, she says. The census asks parents if a child lives in their home. Given that wording, many parents don’t count newborn babies who are still in the hospital.

“I have been talking to our newborn committee at Texas Pediatric Society for about the last year, saying, ‘We need to make sure all our neonatologists remind parents to count your babies,’” she said.

Children in foster care also are five times more likely to be undercounted, according to Texans Care for Children. Either they move homes frequently or foster families incorrectly believe these children shouldn’t be counted because their stay is expected to be temporary.

Overall, children ages 5 and younger are the most undercounted group, Ms. Mitten says. In the 2010 census, these young children were undercounted by 5%, or 102,406 total, according to the group’s website.

“There should be a basic understanding that every single person should be counted, regardless of anything else,” Dr. Gambill said.

Tex Med. 2020;116(3):42-45

March 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page