COVID-19 has given Texas physicians plenty to worry about, but often it’s the collateral damage caused by the disease that haunts them the most.

For Tyler pediatrician Valerie Smith, MD, it’s the knowledge that annual sports check-ups and well-child visits – which normally uncover a host of unsuspected health conditions – simply weren’t happening.

“The focus of an adolescent physical exam … really is on behavioral mental health and social issues, and so those things are particularly a concern right now,” she said. “And we’re just not seeing those kids in the office right now, but we know that those problems are not going away. When I say that keeps pediatricians up at night, I’m not kidding.”

Any physician can look out over the COVID-19 landscape and see important areas of health care tied to their specialty that are being downplayed or ignored as resources pour into fighting the pandemic and scared patients chose not to come to their doctors’ offices.

“Certainly, this pandemic is something we’ve never experienced before, and all the attention on it is justified,” said Lewis Foxhall, MD, vice president for health policy at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “The challenge is that we still have all the problems we had before.”

The pandemic also unleashed two destructive economic forces that make health care delivery more difficult.

First, record numbers of people lost their job-based health insurance as the U.S. unemployment rate hit levels not seen since the Great Depression.

That is especially difficult for Texas, which even before the pandemic had the nation's highest rate of uninsured people at roughly 5 million (www.texmed.org/TexasUninsuredStats). If the state's unemployment rate climbs to 15%, it could add another 800,000 to 1.3 million uninsured to that number, says a study by the Urban Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (As of this writing, the Texas unemployment rate for April was a record-high 12.8%, and the U.S. unemployment rate was 14.7%, according to the Texas Workforce Commission and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

As of May, the Texas Medical Association had received numerous calls from physicians whose patients ceased treatment, including cancer care, as a result of losing health care coverage.

Second, medical practices have been hit hard financially by COVID-19. It wasn’t until late April that Gov. Greg Abbott began loosening an executive order he issued in March restricting non-urgent elective surgeries and procedures to preserve personal protective equipment and to limit the spread of the disease.

These goals were achieved, but patient visits plunged. In response to a TMA practice viability survey taken in May, 66% of physicians reported that their patient volume decreased by at least half since the start of the pandemic; 63% reported losing at least half of their practice revenue.

And yet many physicians still did plenty of work – like fielding non-telemedicine phone calls and answering emails from patients – that largely was not compensated under current insurance rules, says Erica Swegler, MD, an Austin family physician and member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force.

“The payment system is not changing to support primary care at all in the pandemic,” she said. “The fact of the matter is that we’re at risk of [losing large numbers of] independent physicians, and those physicians are a critical part of the health infrastructure of Texas and other places. The impact is that we’re going to see health care costs increase … if we drive everybody into large hospital-based systems or large groups.”

More expensive care could exacerbate a long-standing physician shortage and cause more people to delay routine-but-important doctor visits, Dr. Swegler says. Already she’s seen patients hold off on treating injuries like dog bites or lacerations until the wounds become infected.

Medical practices and hospitals have responded to this problem with sweeping steps to make in-person visits safe in order to reassure patients, says Eugene Toy, MD, of Houston, chair of the American College

of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Texas District (www.texmed.org/CovidPracticeStandards).

“I don’t think that patients are aware that all of the doctors’ offices and the hospitals have really taken precautions and extra steps to make sure that patients are cared for in a safe manner,” Dr. Toy said. “They should be confident that they won’t be infected with COVID-19 in our health care settings.” (For a downloadable poster, visit tma.tips/COVIDposter.)

Also, the sudden surge in telemedicine offers both patients and physicians a lot of hope that physician visits can be done a new way, says Thomas J. Kim, MD, an Austin psychiatrist and internist who has run several telemedicine programs. Though not a silver bullet, telemedicine can help Texas maximize the state’s medical resources, he says. (See “The Tele-Future Is Now,” page 14.)

Here are four of the biggest health concerns that physicians contacted by Texas Medicine cited as getting sidelined during the pandemic.

Mental health

An April poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 45% of adults in the U.S. reported that their mental health has been negatively impacted due to worry and stress over COVID-19 (tma.tips/CovidMentalHealth).

It’s not hard to see why. The pandemic drives many common symptoms of distress, including anxiety, depression, and increased drug and alcohol use, says Dr. Kim. And yet the full extent of the pandemic’s impact on mental health will probably remain unclear for a long time.

“I don’t think we’ve wrapped our arms around it because we’re still in it,” he said.

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals have been in short supply nationwide for many years. So while COVID-19 didn’t create the shortage of mental health care in Texas, it did amplify it dramatically, Dr. Swegler adds.

“I’ve had people call 80 out of 80 mental health providers on their network plan, and none are accepting new patients,” she said. “That was before this [pandemic] started, and this is only making it worse.”

And those are people with health insurance. People without insurance are the ones facing the greatest amount of stress and anxiety, Dr. Swegler says.

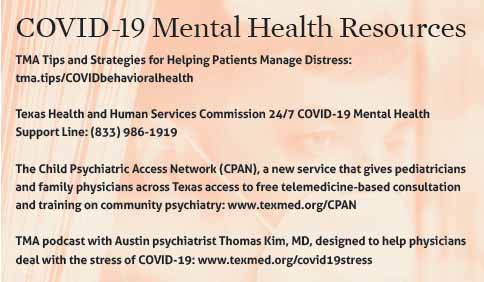

“In general, if you lose your job and you lose your insurance and you don’t have resources, finding care for those individuals is what’s difficult,” she said. (See “COVID-19 Mental Health Resources,” page 23.)

While the pandemic is a natural disaster, it’s not like hurricanes, tornadoes, or other disasters we’re used to, Dr. Kim says.

With hurricanes Katrina and Rita for instance, “there were functioning cities outside the hurricane zone,” he said. “This pandemic is unprecedented due to the absence of any safe quarter.”

Still those types of disasters give us the best template for what is likely to happen this time around in mental health, Dr. Kim says. In most disasters the event is followed by a first acute wave of mental distress as people cope with the disaster. That is followed by a second much longer wave that tends to affect more people in more profound ways.

“It’s a pretty good bet that we’ll observe a significant increase in difficulties across every life domain, including suicidality,” he said.

Dr. Kim remains optimistic that the expansion of telehealth since COVID-19 will help compensate for at least some of the shortcomings in mental health delivery, bringing more patients and physicians together.

People also are discovering the value of simply caring for each other, he said. For instance, they are finding new routines to educate children, helping neighbors with errands, and rekindling personal interests or hobbies – all of which can have an enormously positive effect. “Focusing on the good things in our life can help reframe the not-so-good things as manageable rather than overwhelming,” he said.

Vaccination and children’s health

Vaccination of children and orders for vaccines dropped sharply in late March, right after the U.S. government announced the COVID-19 national emergency, according to a May study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (tma.tips/CDCstudyVaccines). That could herald outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in the coming months, the study says.

This was not news to pediatricians or family physicians, who already had sounded the alarm that children had abruptly stopped seeing their doctors and getting vaccinated. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians estimate pediatricians and family doctors are seeing only about 20% to 30% of the volume of children who normally should come in for appointments, though telemedicine has offset that somewhat.

“From a well-child volume standpoint, it is about half of what we typically see this time of year,” said Dr. Smith, the Tyler pediatrician.

Texas physicians will have to be aggressive in promoting all types of vaccination, says C. Mary Healy, MD, associate professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force.

“A big target will have to be ensuring that as many people as possible [of all ages] get their flu vaccine this year so we’re not dealing with the flu as well as COVID-19,” she said. “But also, we may have outbreaks of things like pertussis and measles.”

Dealing with multiple disease outbreaks would not be dangerous only to patients, Dr. Healy says. It would further stretch resources needed to fight the pandemic.

“[Any disease outbreak is] also hugely demanding in terms of public health in contact tracing and in interventions,” she said.

Vaccines are not the only problem facing pediatricians. Children also are especially vulnerable because they frequently don’t know how to articulate their health problems to people around them, Dr. Smith says.

Telemedicine can help physicians close that gap with some pediatric patients. In fact, many children don’t like the masks physicians now wear during office visits, and telemedicine allows Dr. Smith to take off her mask while on the screen and talk to older children.

But telemedicine has limits. Vaccines cannot be administered in a telemedicine visit. Also, the youngest children often don’t know how to react to a physician appearing on a computer monitor.

“It’s hard to get in a conversation with a 2-year-old,” she said.

In late March, TMA and the Texas Pediatric Society urged Texas Medicaid to temporarily approve payment for telemedicine for Texas Health Steps well-child visits. As of press time, HHSC had extended the new policy through June.

Cancer and chronic ailments

Cancer screenings were one of the elective procedures Americans were asked to delay starting in March. As a result, screenings for breast, cervical, and colon cancer dropped between 86% and 94%, according to data from electronic medical records vendor Epic.

“Unfortunately, new cases [of cancer] continue to occur,” says Dr. Foxhall of MD Anderson. “We’re just not able to find them, work them up, and get them to treatment.”

Dr. Foxhall works with mobile mammography and colorectal screening programs that operate in collaboration with federally qualified health centers. They target low-income and uninsured populations in an effort to reach people who otherwise would have a hard time getting screened.

The longer medical facilities wait to reinstitute those programs, the more patients will have advanced disease and more deadly outcomes, Dr. Foxhall says.

Irrespective of the pandemic, “we have about 42,000 people who are expected to die of cancer here in the state [annually], and reports show that 40% to 50% of those could be avoidable,” he said. “So if we do those things to prevent cancer or find cancer early then, combined with our rapidly improving treatments, this [cancer] is a pandemic we can do something about.”

The decline in vaccination rates caused by the focus on COVID-19 also has a direct tie to cancer-prevention efforts, Dr. Foxhall warns. The vaccine for human papillomavirus (HPV) prevents cervical and head-and-neck cancers, while the hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis C treatment help reduce liver cancer and chronic liver ailments. All three were under-used before the pandemic began, he says.

“[Hepatitis infections of all kinds] are especially a problem in the Rio Grande Valley area, where they’re combined with other conditions like diabetes, which tends to create chronic inflammation in the liver that leads to liver cancer,” Dr. Foxhall said. “So COVID’s not the only virus out there causing problems.”

Physicians also must pay upfront for these vaccines – about $2,000 for a minimum of 10 doses, an additional barrier for small-group or solo physicians, Dr. Swegler says.

Patients with other chronic conditions are keeping their physician at arm’s length as well, says Jan Patterson, MD, an infectious disease specialist in San Antonio who also sits on TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force.

“We have a number of patients at our infectious disease clinic who have not followed up for their chronic conditions, whether that be osteomyelitis, or treatment for another type of long-term infection, or recurrent urinary tract infection,” she said. “We’ve been able to make up for some of that by doing video and telephone visits, so that’s helped a lot for patients who really do need follow-up. But there are some who have cancelled their appointments and haven’t rescheduled.”

COVID-19 has not been able to unseat heart disease as the leading cause of death in the U.S. But because heart disease has been strongly tied to COVID-19 deaths, many heart patients have been reluctant to go near a medical facility, Dr. Patterson says.

“With a heart attack, sometimes the symptoms are very subtle,” she said. “It may feel like chest pressure, it may feel like indigestion, and there’s a been a fair amount of public education that people should come in if those feelings persist. But those people are not coming in.”

Childbirth and contraception

COVID-19 does not appear to affect pregnant women or women of child-bearing years disproportionately – unless they have comorbidities like heart disease, diabetes, severe obesity, or another underlying condition, says Houston OB-Gyn Dr. Toy.

But indirectly, COVID-19 has had a big impact on pregnant women in two ways: first on maternal mortality, and second on efforts to promote long-acting reversible contraception.

The overall U.S. maternal mortality rate is 17.4 per 100,000, but the rate for African American women is 37.1 per 100,000, while the rate for women over 41 soars to 81.9 per 100,000, according to CDC.

Before COVID-19, Texas hospitals were making progress on addressing maternal mortality by using protocols designed by the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Care (AIM), Dr. Toy says. These AIM “bundles” are designed to help hospital staff respond quickly to common maternal problems like hemorrhage or hypertension. (See “AIMing to Save Lives,” April 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 21-23, www.texmed.org/AIMSavesLives.)

The problem now is that hospital staff are understandably distracted from the goal of reducing maternal mortality, Dr. Toy says.

“It’s not that the AIM bundles are not being utilized, but I’ve talked to [staff at] many different hospitals in our state, and everybody is just trying to get through this crisis,” he said.

Many patients are so fearful of hospitals that they’re opting to give birth at home using midwives or going to birthing centers. While those options are usually fine for healthy women, many women don’t realize they might have underlying health issues that make such a move needlessly risky.

“A lot of our patients don’t recognize that it’s important for them to be assessed by a physician and that they deliver at a hospital,” Dr. Toy said.

As of May, TMA also received reports from OB/Gyns and family physicians about drops in prenatal visits, potentially increasing the number of women with undiagnosed illnesses and problem pregnancies.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) – another tool designed to help reduce maternal illness and death – also has suffered because of the pandemic, he adds. Women who have just given birth can opt to obtain LARCs to help them space out births. (See “Breaking Down Barriers,” January 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 42-44, www.texmed.org/LARCS2020.)

But that’s not possible if they’re not giving birth in hospitals or declining to make follow-up visits with a physician, Dr. Toy says.

As with many other health problems, helping patients access long-term contraception was difficult before the pandemic. Now, it’s much more so, Dr. Toy says.

“It’s so much more cost-effective for everyone – the patient, the health care community, and the state – for patients to have reliable contraception,” he said. “And it’s a big problem [now] for patients.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(7):22-28

July 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page