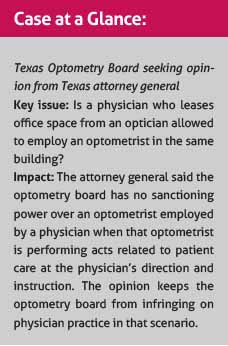

An opinion by the Texas attorney general will keep the Texas Optometry Board (TOB) from exerting influence over the practice of medicine – to a certain point.

In 2019, the optometry board asked Attorney General Ken Paxton for an official opinion on arrangements in which an optician acts as the landlord for a physician, who in turn employs an optometrist in the optician-leased building.

TOB argued such arrangements run afoul of the state’s optometry law, which separates the practice of optometry from the influence of opticians, who manufacture and sell ophthalmic products. The board said an exception in the law – which prevents TOB from interfering with physician-directed patient care – didn’t apply to optometrists. But the Texas Medical Association and Texas Ophthalmological Association (TOA) argued that it did.

TOB asked the attorney general about the board’s power to sanction optometrists or opticians in that arrangement – which TMA believed, if allowed, would amount to another profession’s board exerting influence over physician practice. TMA said if the exception didn’t apply to optometrists, it “would interfere with where a physician may practice and to whom they may delegate treatment.”

Attorney General Paxton’s April opinion agreed with TMA that physician-directed patient care by optometrists was part of the exception. That part of the opinion was a win for medicine. However, the attorney general did not say the exception covers everything an optometrist does while employed by a physician, which TMA had hoped for to remove any hint of optometry board regulatory authority over whom physicians hire.

“It wasn’t as clear-cut as we would have liked,” said Dallas ophthalmologist and TOA President Mark Mazow, MD. “But in general, it seemed to say ophthalmologists are regulated by the medical board, optometrists are regulated by the optometric board, and that’s really it. It just didn’t seem to quite close the door,” possibly leaving “wiggle room” for situations in which the optometry board might have some regulatory power.

For the most part, the decision preserves physician authority, says Austin ophthalmologist Kristen Hawthorne, MD, whose practice has an optical shop and has employed an optometrist in the past. “I was happy that the AG seems to support the practice of medicine by licensed physicians, and that would include any and all ways that a physician can best serve the patients, which may be through different providers who are helpful in different ways.”

TOB Executive Director Chris Kloeris declined to comment for this article.

One law, two visions

The Texas Optometry Act prevents manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers of ophthalmic goods from “controlling or attempting to control” an optometrist’s professional judgment and manner of practice. As such, the law says a retailer of ophthalmic goods – namely an optician – can’t share “employees, business services, or similar items to or with an optometrist or therapeutic optometrist.”

However, an exception says that law can’t interfere with a licensed physician’s right to “direct or instruct a person under the physician’s control, supervision, or direction to aid or attend to the needs of a patient according to the physician’s specific direction, instruction, or prescription.” That exception, in TMA’s view, keeps the optometry board from controlling physician hiring practices.

In its brief to the attorney general, the optometry board argued that the exception didn’t apply to optometrists because they are “not under a physician’s control, supervision, or direction even if employed in an optometric office owned by a physician.”

“The language ‘a person under the physician’s control, supervision, or direction’ refers only to those persons who are not licensed to independently practice,” the board wrote. “Physicians are specifically authorized to direct or instruct such a person who is under the physician’s supervision to perform a medical act. Optometrists, because of their independent authority to practice optometry, are not included in [the law] authorizing physician supervision.”

In response, TMA cited a 1992 attorney general opinion that already recognized the exception “can include an optometrist employed by a physician,” and that removing physician-optometrist employment relationships from the exception “would penalize and discourage otherwise lawful relationships.” The exception is a broad one, TMA argued, and the Optometry Act addresses potential conflicts of interest in other language. (See “Not Seeing Eye to Eye,” February 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 25-27, www.texmed.org/eyetoeye.)

AG: Patient care a key factor

Attorney General Paxton’s written opinion sided with medicine in situations where the physician-optometrist relationship pertains to patient care under the physician’s direction. He wrote that the law “limits the [Optometry] Board from interfering with certain rights of a licensed physician in specific circumstances.”

“The first is the physician’s right to ‘treat or prescribe for a patient.’ The second is the right of the physician to direct or instruct one under his or her control ‘to aid or attend to the needs of a patient according to the physician’s specific direction, instruction, or prescription,’” Attorney General Paxton explained.

But he also said the law doesn’t completely exempt physicians and their employees.

Whether the exception applies to an optometrist employed by a physician depends on the “nature of the function performed under the physician’s direction or instruction,” the attorney general wrote. A court likely would not read the law as “a blanket exception” for everything someone does under a physician’s direction or instruction “just because they are conducted at the physician’s direction. It operates as a shield when the physician’s direction and instruction of a person … including an optometrist, is to aid and attend to the needs of a patient as specifically directed, instructed, or prescribed by the physician,” the opinion stated.

However, Attorney General Paxton declined to address specific situations in which the exception wouldn't apply.

“The question whether any given set of circumstances will support [Optometry] Board action against a retailer or optometrist involves fact questions that are outside the purview of an attorney general opinion,” he wrote.

Physician authority preserved

Texas Ophthalmological Association Executive Director Rachael Reed told Texas Medicine in a written statement that the association was pleased the attorney general recognized the physician exception in the optometry law.

“Only the Texas Medical Board can regulate, investigate, or discipline physicians and physician practices,” she said. “Furthermore, the Texas Optometry Act itself states that it is not applicable to physicians.”

As for the attorney general declining to apply a blanket exception to the law to everything a physician-directed optometrist does, Ms. Reed says that means “it’s a case-by-case determination as to whether the TOB can enforce its rules against a physician or a physician practice when it believes that an employed [optometrist] has violated TOB rules with regards to a retailer. I am confident that any court would uphold the physician’s authority to delegate medical acts and supervise allied health professions unencumbered.”

Dr. Hawthorne of Austin says the opinion also provides clarity on what an optometrist can do under physician direction, which is helpful when hiring and training optometrists to work in a medical office.

“It does allow an employed optometrist to be an extender for me. When I can show an optometrist seeking employment these documents, it makes it more clear legally what role an optometrist in a medical office may have under physician direction, compared to the scope of practice that optometrist may be used to coming from a purely optometric practice environment,” she said.

According to TMA’s Office of General Counsel, courts are not required to follow attorney general opinions but generally consider them persuasive.

Tex Med. 2020;116(7):33-36

July 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page