Medical schools typically have predictable schedules. The timing of lectures, clerkships, exams, and even extracurricular activities tend to follow in the same grooves year after year. Students can reliably block out even minor events months ahead of time and be confident they’ll take place.

All that changed with COVID-19.

Since March, when the pandemic began closing down schools, businesses, and other institutions across the state, figuring out what comes next in medical school has been anything but predictable, says Swetha Maddipudi, a third-year medical student at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

“Every day is a new day, and the plan you had the previous day [for school] is completely different,” she said.

For students’ safety, schools shut down in-person classes and clinical clerkships in March and conducted the rest of the spring semester online. At press time in June, schools planned to return to in-person classes by the late summer or early fall.

But all that could change as well because of the unpredictable impact of COVID-19, says Beth Nelson, MD, associate dean of undergraduate medical education at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. Spikes in infection rates could prompt a city or region to shut down, causing hundreds of medical students to recalibrate once again.

“If we could have had a clear plan – 100% certain – moving forward, I think [the students] would have been able to adjust,” she said. “But for months, it’s been, ‘This is our best guess, this is our best hope. If everything goes well, we’ll be doing it this way.’ You don’t feel like you have confidence in the timeline.”

While schools were able to adapt classrooms and clinical clerkships – however imperfectly – to virtual formats, medical school benchmark testing temporarily ground to a halt. Prometric, the testing service that administers the biggest medical school exam – the United States Medical Licensing Examination, or USMLE – cancelled all testing dates starting March 17 to revamp its procedures for social distancing.

When the company reopened testing in May, not only was there a backlog, there were fewer seats for each test because of distancing requirements. As a result, students scheduled testing dates only to see them canceled, sometimes abruptly.

“Some of my friends and peers had their exam spots cancelled just days before their exam, and some were canceled the night before,” Ms. Maddipudi said.

Cancellations added to an already pressure-filled medical school experience, says Deborah Conway, MD, interim vice dean for undergraduate medical education and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Long School of Medicine.

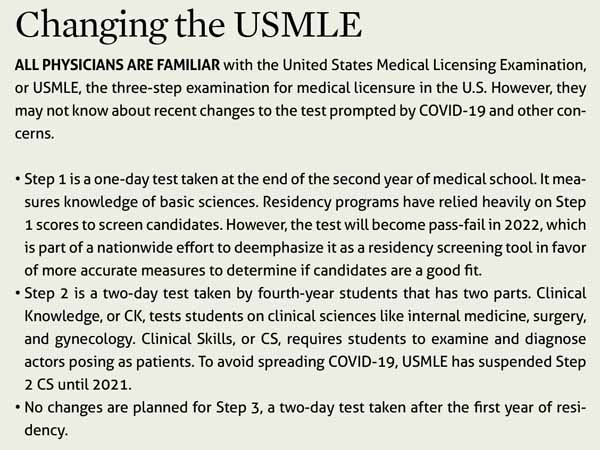

Residency program officials frequently use USMLE test scores to help determine which students get admitted to their programs, she says. (See “Changing the USMLE,” page 36.) Students typically set aside four to eight weeks to study carefully for Step 1 and Step 2 of the USMLE because their careers depend on it.

“So [USMLE tests] were already incredibly stressful events for medical students on a really tight timeline,” she said.

The cumulative effect of all this uncertainty is that today’s medical students are facing pressures that older physicians never faced in medical school, says Robert Carpenter, MD, a bariatric surgeon, clinical associate professor, and head of wellness at Texas A&M University College of Medicine.

This unprecedented situation may lead to some positive long-term changes – like easing the psychological pressures students face, he says. But it’s clearly taking a toll right now.

“You’re going through all the stress that’s normal and natural for a medical student. Oh, and, by the way, you’re doing that in what realistically is a recession … overlaid by the worst pandemic in a century,” Dr. Carpenter said.

Chasing the USMLE

Medical students aren’t the only ones caught up in the testing chaos, Dr. Nelson says. Many college students applying to get into medical school have been unable to take the Medical College Admission Test, or MCAT. As a result, medical schools in many states have opted to drop the MCAT as a requirement, though Texas schools were still mulling that decision in June.

However, the USMLE is the major area of concern. In May, Prometric opened up testing on a limited basis in 10 Texas cities, according to its website. But with cancellations still frequent, students played a risky game of cat-and-mouse as the test’s availability seemed to shift from city to city, Dr. Carpenter says.

For instance, a Texas A&M student might plan to take a test in Austin, find out it’s canceled, and then have to shift to Lubbock at the last minute.

“How do I get, as a medical student with [a lot of time demands], safely from here to Lubbock, take the test, and come back without being exposed [to COVID-19]?” Dr. Carpenter asked.

Ms. Maddipudi checked the Prometric website daily for updates and tried to figure out which city would work for her.

“We were putting in a lot of brainpower each day to anticipate what might happen with our testing spots,” she said. “We had to decide if we should pre-emptively reschedule our tests to a later date that might be safe from cancellations or continue to hope that our testing spot would be safe.”

After six cancellations or reschedules, Prometric expanded testing availability in June, according to the company’s website. After that, the situation began to stabilize, Ms. Maddipudi says, and she was able to schedule a test in San Antonio for early June.

“There came a point where I just wanted to take the test and get it over with,” she said. “I cared less about my performance and more about clearing this hurdle so I could move on to my clinical years.”

Ms. Maddipudi had planned to spend eight focused weeks studying for Step 1. Instead, it took her a hectic 14 weeks, she says. And while the test was over for her, about two-thirds of her fellow third-year students at Long School of Medicine still waited to take Step 1.

Healthy changes

At the start of the pandemic, U.S. medical schools and teaching hospitals withdrew medical students from clinical clerkships at medical centers for their own safety and to preserve the personal protective equipment (PPE) that was in short supply for clinicians.

For many students, this was a psychological blow because they wanted to help fight the pandemic, Dr. Carpenter says. But it also was a professional blow because without clerkships – or with truncated ones – students feared they would become less desirable to residency programs.

Since then, medical schools have wrestled with how to reintroduce students into clinical settings as safely as possible, Dr. Carpenter says.

“You can’t practice medicine without some degree of risk to yourself,” he said. “But how do we teach them to use PPE appropriately and keep themselves psychologically, socially, and mentally well enough to do the right things and make the right decisions to get enough experience to graduate?”

Many clerkships already have been restored, though often in a changed format, says Jennifer Christner, MD, dean of the School of Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. PPE is more available than it was in March, but it’s still in short supply. So medical schools have become creative about ways to get students back in touch with patients, she says.

“We have students who are with their attending [physician] taking the history of the patient outside the room via Zoom while the patient is inside the room,” she said. “So the patient still gets the benefit of being with their attending supervisor, taking the questions that their attending has asked. That’s something that has never happened before.”

It remains unclear how all these changes will affect the 2021 residency match, in part because many of the normal procedures for choosing residents – namely in-person interviews – also have been discontinued, Dr. Christner says.

But at least some of the changes brought about by COVID-19 have been healthy and have improved learning, says Farhan Aziz Mithani, a fourth-year student at Texas A&M.

For instance, students at the school typically do an eight-week rotation and then take an exam that tests their competency. Normally, students would have worked from 6 am to 5 pm each day at the hospital and spent the evening studying for the exam, which they would take at the end of the eight weeks.

But COVID-19 forced the school to cut down the clerkship’s hospital time to four weeks. So students spent the first four weeks studying, took the test, and then did their four weeks in the hospital, he says.

The new schedule had a lot of benefits, Mr. Mithani says. For instance, it allowed him to help more patients while he was in the hospital because he wasn’t worried about studying in the evening. Typically, two or three students might achieve honor status in a rotation, and in this case at least eight did.

At the same time, he and other students were able to relax in the evening after working all day in the hospital, which helped with their peace of mind.

“It’s kind of an intensified study time and intensified hospital time,” he said. “They’ve just divided it up better.”

Already, medical students and physicians are prone to burnout and psychological stress. (See “Battling Burnout,” April 2018 Texas Medicine, pages 10-13, www.texmed.org/BattlingBurnout.) Medical schools should use the changes caused by COVID-19 to reassess how they’re operating, especially if those changes ease the load on students, Dr. Carpenter says.

“We don’t have to continue to perpetuate the cycle of physician education being a point of extreme strain or psychological isolation,” he said. “We can change that dialogue.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(8):34-36

August 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page