For Ogechika Alozie, MD, the COVID-19 crisis conjures up a sense of déjà vu.

Like many physicians, the El Paso infectious disease specialist – who sits on the Texas Medical Association’s COVID-19 Task Force – sees disturbing parallels between COVID-19 and the HIV/AIDS pandemic that started in the early 1980s.

HIV began as a disease affecting mostly white people but settled over time into a much larger threat for Blacks and other people of color, he says. And many of the factors behind HIV’s persistence in those communities have likewise fueled the rise of COVID-19 in the U.S.

“It’s the same set of dynamics that come into play: lack of access to care, lack of prevention, lack of insurance,” said Dr. Alozie, whose practice focuses largely on HIV patients. “It’s an unfortunate legacy that we continue to perpetuate.”

The website for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is blunt about the impact of that legacy (tma.tips/CovidMinorityGroups): “History shows that severe illness and death rates tend to be higher for racial and ethnic minority populations during public health emergencies than for other populations.”

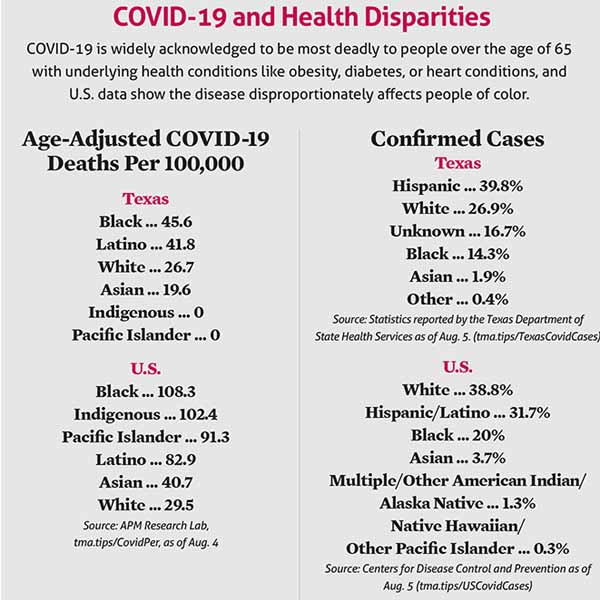

That is certainly happening with COVID-19. (See “COVID-19 and Health Disparities,” page 21.)

Most COVID-19 data show the long-standing social determinants of health stacked against Blacks and Hispanics in Texas, says Eduardo Sanchez, MD. (See "A Social Shift," page 24.) He is former head of the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS), and now chief medical officer for prevention for the American Heart Association in Dallas.

For instance, Dr. Sanchez says, people of color are statistically more likely to:

• Have low-income and “essential” jobs that often result in more direct interactions with people, increasing the likelihood of contracting COVID-19;

• Live in multi-generational or multi-family situations that can make physical distancing difficult;

• Lack health insurance and easy access to health care, which means underlying medical conditions that increase the risk of severe COVID-19 are less likely to be managed well; and

• Lack regular contact with a physician who can help prevent or give timely treatment for COVID-19.

Any of these factors would increase patients’ health risk, but all of them together help explain why people of color often face far more anxiety and stress about COVID-19 than their fellow Americans, Dr. Alozie says.

As with the HIV pandemic, he says physicians have tools – some of them short-term fixes and others long-term policy goals – that can help people of color cope better with COVID-19. Some are relatively easy and are already being done by many practices, while others will require rethinking the way health care is delivered.

“Inequality and racism aren’t genetic, they’re systemic,” he said. “So it’s no surprise that our health care outcomes are exactly what we create.” (See “A Texas-Size Problem,” June 2017 Texas Medicine, pages 41-47, www.texmed.org/TexasProblem.)

Physicians reach out

Education is one of the most important short-term steps physicians can take, says Blythe Mansfield, MD, a consulting physician with Corporate Medical Advisors, a Houston company that provides medical director services.

In Black and Latino communities, she has heard wildly untrue theories concerning COVID-19. For instance, some said that only old people catch it, or that only people of Asian descent were in danger because it originated in China.

“Early on there were a lot of rumors, and education wasn’t getting to the community,” she said.

Physicians can help counteract those rumors by speaking up in public forums like social media and the local press, Dr. Mansfield says.

The Texas Medical Association has prepared extensive materials for physicians to use that provide accurate, science-based information for the public (www.texmed.org/Coronavirus).

Physicians who haven’t already done so should educate their patients, says Salina Mostajabian, MD, a pediatrician at People’s Community Clinic in Austin, where most patients are Latino.

Once COVID-19 hit Texas in March, the clinic quickly drew up a list of patients who would be most vulnerable to the disease – those with respiratory ailments or conditions like diabetes – and began contacting them, Dr. Mostajabian says.

“[We were] making sure that they were up-to-date on their follow-up [visits], that they had their medications available, and that they knew who to contact in the clinic in case they were sick,” Dr. Mostajabian says. “And [we] let them know that they were at higher risk.”

Like virtually all Texas clinics, People’s scrambled to provide telemedicine services once the pandemic started.

“We’ve had to build up our telemedicine protocols from scratch,” Dr. Mostajabian said. “That wasn’t available before.”

Unfortunately, many minority patients have had to build their telemedicine capabilities from scratch as well because they don’t have the equipment or infrastructure to make video calls, she said.

“We have patients coming in from a wide geographic region, and in some areas internet access is an issue,” she says.

In those cases, the clinic has IT experts try to contact patients to establish video links, Dr. Mostajabian says. If all else fails, they encourage patients to simply use the phone to call in.

Patients still need face-to-face visits, and that poses its own problems. Some do not have face masks or other equipment that could keep them safe, Dr. Mansfield says, so physicians may need to supply them.

Likewise, patients may need help from their physician in arranging transportation to and from office visits, Dr. Mansfield says. In many cases, patients don’t have cars or are unable to drive. Patients who would normally use mass transit may face high risk of COVID-19 infection if the proper precautions aren’t taken, she says.

Helping patients figure out transportation options “would remove some of the burden of getting to the doctor,” Dr. Mansfield said.

Matters of trust

Matters of trust

Even physicians who make these efforts shouldn’t be surprised if they are met with skepticism at times from Black and Latino patients, says Janeana White, MD, an internal medicine and pediatric specialist who is also the medical director for disease control and clinical prevention at Harris County Public Health.

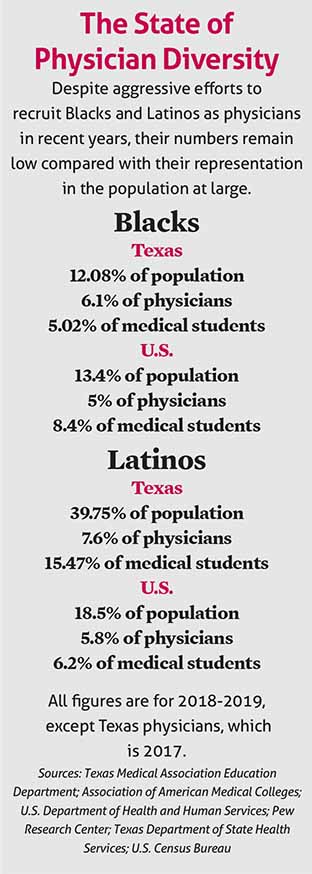

Many people in these groups frankly don’t trust medicine, in part because they see very few people like themselves represented among physicians, she says. (See “The State of Physician Diversity,” left.)

“If you don’t see people who represent you in health care, you’re going to be less likely to trust the health care system and less likely to get health care,” Dr. White said.

Physicians today also must contend with a history of open discrimination against Blacks and Latinos in medicine, Dr. Mansfield says. The infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments on African American men in Alabama between 1932 and 1972, and the research on Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells without her consent in 1951 happened decades ago, but these incidents are fresh in the minds of many people of color, she says.

So are more recent signs of bias. For instance, academic studies have shown that Blacks and Hispanics still are systematically undertreated for pain (tma.tips/VirginiaPainStudy).

But in many cases, people of color never even make it to the physician’s office, Dr. Mansfield says. That’s because Texas has the highest population of uninsured in the U.S. – 5 million out of a population of 29 million in 2019. And people of color in general have higher rates of uninsurance than whites (27% of the Hispanic population is uninsured, 16% of Blacks, 18% of American Indians/Alaska Natives, 16% of Asians/Pacific Islanders, 12% of whites, 12% other, according to the Urban Institute).

Texans say health care is the toughest living expense for them to afford, according to a 2019 poll by the Episcopal Health Foundation. Fifty-five percent of Texans say it’s difficult for them to pay for health care, including 27% who say it’s “very difficult” (tma.tips/TexansAffordHealthCare).

Physicians should look for ways to persuade policymakers to help eliminate disparities in coverage by backing affordable health insurance options, Dr. Sanchez says.

“It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out that if you don’t have health insurance, you’re going to delay care that needs to be addressed,” he said.

Likewise, greater public health spending can stop or curtail disease outbreaks before they become epidemics, Dr. Sanchez says. In the case of COVID-19, it would have allowed for more epidemiologists to be on hand to educate both physicians and the public, and it would have allowed for faster testing and contact tracing.

In 2019, Texas tied with Kansas for 40th among the 50 states in public health care spending, according to the United Health Foundation America’s Health Rankings. Texas spent about $60 per person, below the U.S. average of $87, the group says.

Physicians also should get a better feel for where their patients live because that shapes their health, Dr. Sanchez says.

For instance, a 2019 report by the Episcopal Health Foundation showed that just five miles to the east of the Texas Medical Center in Houston, in the predominantly Black Sunnyside neighborhood – which has faced high crime and unemployment rates – life expectancies can drop to as low as 66 years. But five miles to the west of the center in Bellaire, life expectancies in the safer, higher income, and predominantly white suburb rise to 87 years.

Those disparities show up in COVID-19 rates as well. On July 16, the 77033 ZIP code in Sunnyside had 462 reported cases of the disease, while the 77401 ZIP code in Bellaire had 59, according to the Harris County Public Health dashboard (tma.tips/HarrisCovidTracker). Adjusted for population differences, Sunnyside would have had just 94 cases if that ZIP code had the same COVID-19 infection rate as Bellaire did.

This kind of geographic information should have a direct bearing on how physicians treat the Black and Latino patients who live in neighborhoods similar to Sunnyside, Dr. White says.

“If you don’t have safe places to walk, safe places to play, and I’m encouraging you – someone who is a diabetic – to go out and get more exercise … then I’m writing a prescription that [the patient] can’t support,” Dr. White said. “We can’t just look at the coronavirus and say, ‘Here we go again,’ when it comes to heath care and inequities.”