Most fourth-year medical students have one overarching goal – land a good residency in their specialty of choice by graduation. That’s why they become very familiar with the process for doing that.

“There’s been a pretty standard ebb and flow to the way the [residency] application cycle works,” says Tucker Pope, a fourth-year medical student at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School.

Normally, he says, selection goes like this: In July and August, students apply to graduate medical education (GME) programs and obtain letters of recommendation from professors. In September, the residency programs begin reviewing applications and then hold in-person interviews with students from November to February. Selections are announced on Match Day in March.

But COVID-19 has upset that schedule, in part by interrupting test dates for the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) – the three-step examination for medical licensure in the U.S. for allopathic students – as well as the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Exam of the USA for osteopathic students. (See “Testing Boundaries,” Texas Medicine, pages 34-36, www.texmed.org/TestingBoundaries.)

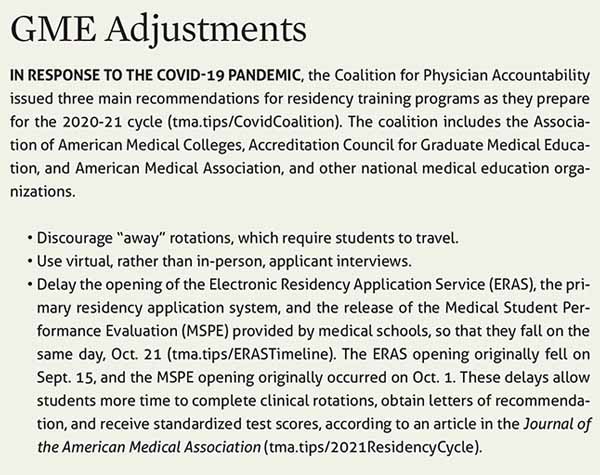

Residency programs have responded by delaying the selection schedule by weeks or months. As of this writing in late July, the opening date for residency programs to accept student applications had been pushed back from Sept. 15 to Oct. 21.

The pandemic also has forced GME programs to revise their criteria for selecting residents, says Jennifer Christner, MD, dean of the School of Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Until this year, residency directors typically screened candidates using grades and scores from Step 1 and Step 2 of the USMLE, she says. And for certain specialties, “away rotations” – third- and fourth-year clinical clerkships at medical facilities outside their home institution – served as an audition for some residencies, which would bring in leading candidates for personal interviews.

However, the in-person interviews and away rotations are now largely off the table for most students to prevent spreading COVID-19, consistent with guidance from national organizations like the Association of American Medical Colleges. (See “GME Adjustments,” page 36.)

A few residency programs experimented with video interviews even before the pandemic. But they overwhelmingly preferred in-person interviews, and the switch to virtual interviews will be a tough transition in many cases, Dr. Christner says.

“For many specialties, that in-person interview is your gut check – this person is or is not going to fit in with my program,” she said.

On top of this, students, medical school faculty, and residency directors all understand that the pandemic could force still more changes and inject more unpredictability into the process, says Tricia C. Elliott, MD, chief academic officer at JPS Health Network in Fort Worth and a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education.

“This has been a day-by-day, sometimes moment-by-moment process,” she said. “We’ve learned that we just have to have the flexibility to adapt to the changing circumstances.”

From in-person to online

Students and residency directors agree the absence of in-person interviews represents the biggest change. Candidates typically travel to meet the program director and the current residents.

“There’s a pre-interview dinner the night before [the main interview], and usually the residents are there, and you can get a sense for what the residents are like and what they like about the program and how they get along with each other,” Mr. Pope said. “Not having that is going to make it harder to figure out which programs are a good cultural fit. Instead, we might just be going off of a PowerPoint on Zoom.”

And with virtual interviews looming, medical schools are adjusting their interview training to online formats, says Steve Smith, PhD, associate dean for student affairs at Dell Medical School. While medical students as a group are technologically savvy, practicing remote interviews has forced a shift in thinking for faculty and students alike.

“We had a process on how to give a good interview, and we’re having to change that,” he said. “You obviously don’t focus on giving them a good, firm handshake. And how do you keep eye contact?”

Some residency programs may have a bias toward local students because they see those students’ work and build relationships with them, says Dr. Elliott. But without in-person interviews for all residency candidates, that tendency could become more pronounced, she says.

“We’re going to have to intentionally and mindfully make sure we eliminate some of that bias,” she said. “We’re going to need to look at those candidates who are beyond our local students and make sure we’re engaging them. It probably can’t just be a one-time engagement. It’s going to need to be a way to create some kind of relationship so the students can really get to know us.”

Like so much of the residency selection process these days, the details of creating that sustained engagement are still in the works for many programs, Dr. Elliott says. “It’s not clear how we’ll do that,” she said. “But each school, each health system, each GME director like myself is putting together a nice group of folks that will include residents and faculty and program directors and program coordinators and staff to figure out what that could look like.”

Students face other changes in the application process as well. For instance, to keep residency programs from being overwhelmed, many specialty society guidelines call for limiting the number of applications students can make to residency programs. In the past, students were free to apply to as many as possible.

A new spin on rotations

The pandemic also prompted U.S. medical schools and teaching hospitals to withdraw medical students from clinical clerkships at all medical centers for their own safety and to preserve personal protective equipment (PPE).

This frustrated students who felt it was their duty to treat COVID-19 patients. But it also came as a professional blow because without these clinical rotations – or with truncated ones – students feared they would become less desirable to residency programs.

Many clerkships have been restored, though often in a changed format, Dr. Christner says. For instance, because PPE still is in short supply in many places, schools have reduced students’ exposure to patients by cutting training time in hospitals, or by having students use Zoom and other virtual formats to communicate with patients.

It’s unclear how these adaptations will affect resident selection, she says. But virtually all medical students will face the same limitations imposed by COVID-19, which residency programs are likely to take into consideration.

Still, students typically can gain exposure to their specialty at their home institution, says Nikita Dhir, a fourth-year student at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine in Lubbock. For instance, pediatrics and internal medicine generally have plenty of clinical rotations for students.

However, for many highly competitive specialties like orthopedic surgery or plastic surgery, students may not have access to training at a nearby medical facility, Ms. Dhir says. For them, away rotations are vital for getting experience and demonstrating how well they can perform in their specialty.

In those cases, some specialty societies and medical schools are encouraging students to find the closest program possible, such as at an in-state medical facility, Dr. Elliott says.

The lack of away rotations could make the residency selection process more equitable, says Thomas Blackwell, MD, associate dean for GME at The University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine in Galveston. Away rotations involve living in another city for weeks, and many medical students cannot afford to do them. Eliminating them levels the playing field for those students, he says.

Both Ms. Dhir and Mr. Pope plan to rely on networks of alumni and current residents to help them investigate the culture of various GME programs.

Dell Medical School students are at a disadvantage because the school has graduated only one class so far, and those graduates have just started their residencies, Mr. Pope says. Fortunately, there is an informal network of Texas residents who have made it clear they’re open to giving advice.

“There’s a great community of residents on Twitter who are saying, ‘Hey, if you’re interested in applying for this program, feel free to DM [direct message] me,’” he said. “So I think there’s going to be a lot more leaning on that information network.”

It is precisely because there are so many new obstacles that schools are bending over backward to give their own students an edge, Dr. Christner says.

“If anything, [students] are probably getting more one-on-one attention from faculty, especially their clerkship directors, than they’ve ever had before,” she said.

And yet the challenges remain daunting for students and residency programs.

“We’re all in the same boat, and we want to do the best for our students,” Dr. Christner said. But she added: “It’s going to be a tough year this year.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(9):34-36

September 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page