COVID-19 has thrown a wrench into several aspects of medical education, and that includes suspending until 2021 one section of the three-part test that aspiring physicians must take to obtain a medical license.

Naturally, medical students are pleased, but many medical school professors and administrators are happy with the delay as well. In fact, they question whether that part of the test is needed at all.

“If something is so expendable that we can stop doing it in a crisis, why should we return to it?” said Charles Cowles, MD, chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education. He is associate professor of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

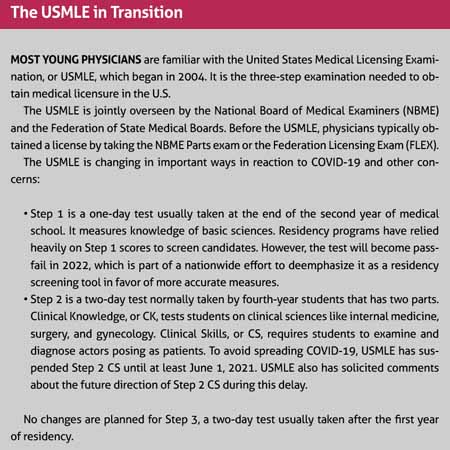

The exam in question is part of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), a three-step test. Step 2 of the USMLE, which is typically taken by fourth-year medical students, is broken into two parts. One focuses on clinical knowledge (CK); the other demonstrates clinical skills (CS). (See “The USMLE in Transition,” page 37.)

Once the pandemic began, officials at the National Board of Medical Examiners and the Federation of State Medical Boards – which jointly oversee the USMLE – suspended Step 2 CS because it involves close human interaction. Each medical student must go through a mock clinical exam with an actor pretending to be sick. That could potentially endanger the students and actors, and it requires scarce personal protective equipment.

Typically, fourth-year medical students must take the clinical skills exam as a prerequisite for graduating and qualifying for a residency. But because of the delay, students like Sarah Miller, a fourth-year student at The University of Texas at Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine in Edinburg, probably will take it after June 1, 2021, after she’s in residency.

“By the time I take it, I will already be seeing patients,” she said. “[By then], it’s hard to see the point of having to pay $1,300 to go take an exam to prove that I can see patients.”

A long time coming?

Step 2 CS is designed in part to assess how well medical students communicate with patients. The exam was originally developed for international medical graduates in 1998 and expanded to other medical students in 2004.

Almost since the test expanded in 2004, medical students and educators have called for eliminating it for being expensive and unnecessary. Those demands grew louder with the pandemic-related delay. In July, USMLE program officials asked for input from the medical education community about charting the future of Step 2 CS.

“We plan to use the coming months to revitalize the assessment of clinical skills by identifying the optimal approach to assess clinical skills for licensure,” USMLE states on its website (tma.tips/Step2CSRevitalize).

In response, TMA’s Council on Medical Education outlined its objections to Step 2 CS in a July 31 letter signed by Dr. Cowles and TMA President Diana Fite, MD. Those objections include that the exam:

• Provides limited educational benefits: Test scores are often slow to arrive and there is very little feedback for students or their medical schools to understand why some fail and how they can improve.

• Is expensive: The $1,300 price tag for the CS exam is twice the cost of the CK exam. Also, there are only five cities in the U.S. – Houston, Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia – where students can take it. Most must add the cost of travel and at least one night in a hotel to the total cost of the exam.

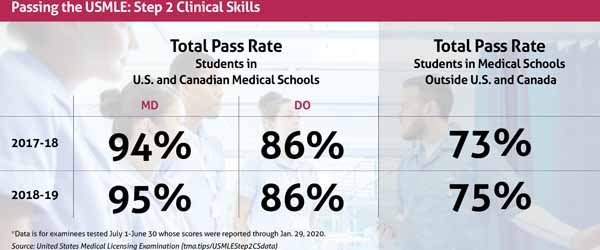

• Has limited value in screening physicians: The CS exam has an exceptionally high passage rate – 95% in 2018-2019 – indicating that the exam does little to weed out physicians who are deficient in clinical skills, the letter says. (See “Passing the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills,” page 40.)

Getting rid of Step 2 CS might be the answer, but so might a more targeted exam, says Beth Nelson, MD, an internal medicine specialist and associate dean of undergraduate medical education at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School.

For instance, rather than testing all medical students, it could be used to focus on those with identified weaknesses in a clinical skill like communication or a professional lapse, or those who have left medicine for some reason and wish to return.

At the very least, USMLE could offer the test in more places to make it less expensive for students, Dr. Nelson says.

“Given this pause, it really is time to ask ourselves, ‘What does this exam provide the medical community and the patients, and where does it really have value rather than as something that is just a historic relic?’”

Layers of stress

Opposition to the Step 2 CS in its current form is widespread among medical educators in part because it creates unnecessary layers of stress for fourth-year students, says Gary McCord, MD. He is a radiologist and associate dean for student affairs at Texas A&M University College of Medicine.

Most of that stress is tied to money, Dr. McCord says. The current $1,300 cost of the exam rises every year, and the travel expenses can range from several hundred dollars to $1,000 or more, depending upon the distance traveled.

“The thing that [medical students] talk about the most is the cost and travel,” he said. “[Their concern] is less about the exam itself.”

The clinical skills exam ramps up stress in other ways.

Students are forced to take the test during one of the most difficult parts of medical school, Dr. McCord says. Typically, schools advise students to take the exam only after they’ve finished their final third-year clerkship so they have more training under their belts to pass the exam.

But that means students must wait until the start of their fourth year, he says. So the window to take Step 2 CS lasts from July of their fourth year – when testing for the school year begins – until December, he says. After December, it’s too late for students to get exam results back in time for residencies to rank them in the residency match.

“Since they’re doing it July through December, you’re going into prime time for interviewing [for residencies] and doing your final rotations and getting your final letters of recommendation to start applying,” he said.

The test has always garnered at least some opposition, says Stephanie Reeves, DO, a pediatrician and assistant dean for student affairs at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

“When I graduated medical school, it was the second year after they started requiring the test in 2005, and the main complaints then were that it’s just a test to show we were proficient in English and that you’re going to be able to take care of patients in the United States, along with being expensive and hard to get to. And I think the majority of those complaints have remained very similar.”

Step 2 CS assesses other types of clinical skills as well. Unfortunately, the small number of students who fail receive insufficient feedback about what they did wrong to knowledgably change their approach, Dr. Cowles says.

Also, Step 2 CS is largely redundant, says Ms. Miller, the fourth-year student. Most medical schools already teach and give multiple exams for clinical skills, called objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs). By the time medical students take Step 2 CS, they have repeatedly shown their clinical skills competence in their pre-clinical simulations as well as in several OSCEs for clerkships.

“Our schools are already evaluating us in a similar way,” Ms. Miller said.

Success and failure

Many of the students who fail the Step 2 CS are not what schools consider “problem” students who need remediation, Dr. McCord says. Very often they’re highly competent students who probably just had a bad day when they took the test.

“Given the cost and the poor correlation between known competence and who we see passing or not passing this test, I walk away from [Step 2 CS] wondering if it is really protecting the public at all,” he said. “My personal feeling is, no.”

Repeated failure on the Step 2 CS should be a potential red flag, says Robert Carpenter, MD, a bariatric surgeon and director of wellness at Texas A&M. But in most cases, one-time failure is seen by residency directors as a bureaucratic hassle, not a reason to rule out an otherwise desirable applicant.

“I can’t speak for all residencies or specialties, but [from] a former associate program director’s standpoint, we don’t tend to view this as … ‘you’re incompetent,’ but, rather, ‘now we’ve got to take time away from your clinical education and teams to get you re-tested and get you through that and then back into the residency program,’” he said.

Opponents to Step 2 CS greatly outnumber its supporters. But supporters do speak up from time to time, and they argue that having students tested on clinical skills in medical school is not enough.

Until the Step 2 CS came along, clinical skills teaching at medical schools was uneven, supporters argue. Without a national standard, they say it is still too easy for otherwise good students with weak clinical skills to graduate and begin treating patients (tma.tips/DefendingStep2).

The Step 2 CS should get credit for pushing medical schools toward formally assessing clinical skills, Dr. Nelson says. When it began in 2004, some schools already had incorporated clinical skills into their curriculum, but many had not. The Step 2 CS encouraged greater emphasis on clinical skills education because students needed it to obtain a medical license, she says.

If Step 2 CS were to go away, would schools backslide and either slow down or stop teaching clinical skills?

Probably not, Dr. Nelson says. Medical education has changed dramatically in the last two decades, switching from written assessments of knowledge to clinical skills assessment through direct observation or training using simulation labs and similar methods, she says.

“Awareness of the need to demonstrate clinical skills is part of the required competencies of all medical schools at this point.” Dr. Nelson said. “It’s become part of the graduation competencies. … It’s become part of our culture.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(11):36-40

November 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page