When physicians make one of the most difficult decisions in health care – whether to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from a patient – the Texas Advance Directives Act (TADA) allows them to exercise their moral conscience and medical judgment.

But since its 1999 passing, the law has faced repeated legislative and court challenges. The Texas Medical Association is weighing in on the latest affront after an appeals court decision that TMA believes “threatens the integrity of the medical profession in Texas” and creates major uncertainty around end-of-life care.

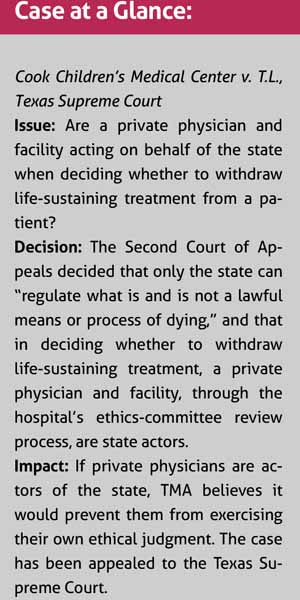

In Cook Children’s Medical Center v. T.L., the Second Court of Appeals decided that TADA’s medical ethics-committee process isn’t adequate due process for resolving disputes between an attending physician and a patient’s medical decisionmaker over starting or continuing life-sustaining treatment. That decision ordered the case sent back to the trial court where it originated.

The appeals court stopped short of declaring the law unconstitutional. But that’s “effectively” what appellate justices did to “an important Texas statute,” the hospital in the case, Cook Children’s, said in its plea asking the Texas Supreme Court to review the decision.

Part of the appeals court’s rationale: Private physicians and hospitals deciding whether to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from a patient are performing “state action” – that is, the state of Texas is delegating to them its power “to regulate what is and is not a lawful means or process of dying.” If physicians are state actors, they must follow the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits the state from depriving a person of life without due process. And TADA, the court said, does not adequately provide that due process.

That interpretation troubles TMA, the Texas Alliance for Patient Access (TAPA), and the Texas Hospital Association (THA), who call the case a “broadside constitutional attack” on the advance-directive law. They joined a broad group of organizations – including the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops and Texas Alliance for Life – in a friend-of-the-court brief to the Texas Supreme Court.

To Robert Fine, MD, clinical director of Baylor Scott & White’s Office of Clinical Ethics and Palliative Care, the due process patients and families get in the ethics committee law is “pretty basic and very fair.” Dr. Fine, who helped craft the law more than two decades ago, says the appeals court’s opinion “is basically saying to physicians, ‘Your medical license only entitles you to serve as a waiter in a restaurant – delivering whatever the customer orders. Your license does not entitle you to exercise your medical judgment and maintain your moral integrity.’”

While Dr. Fine adds he has great respect for the courts and jurists, “I just think the judges have not adequately thought through the implications of saying, ‘When you’re making a life-or-death decision, you’re taking on this [role] of the state, and you are now a state actor.’”

A wrenching disagreement

The state’s medical ethics committee process under TADA covers situations in which a physician believes life-sustaining treatment would exacerbate or extend a patient’s suffering, and then refuses to start or continue that treatment contrary to the wishes of the patient or someone else making the patient’s health care decisions.

The law allows the doctor to present the case to the facility’s ethics committee. If the panel agrees with the physician that the treatment is medically inappropriate, the physician and the facility must make “a reasonable effort” to transfer the patient to another facility within 10 days. Then, if no other facility will take the patient, the physician would be immune from civil and criminal liability for withdrawing the treatment.

But the appeals-court’s decision in Cook Children’s v. T.L. throws the application of the law into doubt.

According to court documents, “T.L.” was born prematurely in February 2019 with a congenital cardiopulmonary defect. Cook Children’s Medical Center in Fort Worth admitted her to its cardiac intensive care unit.

Court documents detailed “heroic” efforts by the child’s care team at Cook Children’s. But a consensus medical judgment emerged that T.L. was suffering, and the intensive care unit team viewed continuing life-sustaining treatment as “cruel” and “unnatural,” deciding that discontinuing it would be in her best interest.

Conversations with the child’s mother failed to produce agreement with the care team on discontinuing the treatment, according to court documents. In late September 2019, the child’s attending physician invoked the ethics-committee process. The panel met late in October 2019, hearing from both the attending physician and the child’s mother. The committee unanimously agreed that life-sustaining treatment should be discontinued, opening the 10-day window to find another facility to continue treating the child.

Challenging the law

On the last day of that 10-day period, the mother filed suit in a Tarrant County trial court claiming Cook Children’s interfered with her right to make treatment choices for her child and violated the child’s right to life.

The suit also claimed the law didn’t provide enough due-process protection and asked the trial court to find the ethics-committee law unconstitutional. The mother sought and was granted a temporary restraining order that kept her daughter on life-sustaining treatment.

An attorney for T.L. did not respond to Texas Medicine’s phone and email requests for comment.

Her mother’s suit argued the child hadn’t received due process, and the “risk of an erroneous deprivation – death against her wishes and through Cook’s actions – demands the greatest procedural safeguards.” Because Cook Children’s was using the ethics-committee law “to protect their decision to remove life-sustaining treatment, they are taking state action and are subject to Constitutional regulation.”

She also argued that under the law, “The doctor and ‘ethics committee’ are given complete autonomy in rendering a decision that further medical treatment is ‘inappropriate’ for a person with an irreversible or terminal condition. This is an alarming delegation of power by state law.”

The trial court sided with Cook Children’s, which argued that “under existing law, physicians have no constitutional obligation to provide any particular medical intervention – much less one that violates their ethics and conscience. The [law], therefore, does not deprive anyone of life, or of the power to direct medical care.”

The Second Court of Appeals reversed that decision.

While appeals-court Justice Wade Birdwell said “[m]ost medical treatment decisions made by private health care providers are not traditionally or exclusively public functions,” they decided that “only the sovereign immunity of the state may override a parent’s refusal to consent to recommended treatment for her child.” Therefore, in making such medical decisions, physicians and ethics committees are considered state actors, the court determined.

In asking the Supreme Court to review the case, Cook Children’s contends that a private hospital’s treatment decision is just that – private – not a state action, and state liability protections don’t necessarily convert the hospital into a state representative. The hospital cites several state and federal court precedents.

“The Legislature routinely sets substantive rules for private interactions, and it can provide statutory protections and defenses without converting private activity into state action,” Cook Children’s argued in its court filing. The advance directive law, the hospital wrote, “does not delegate regulatory authority to private hospitals,” and the law’s ethics committee review procedure “recognizes that medical professionals retain the right to refuse to perform improper interventions.”

The appeals court’s opinion “effectively creates a constitutional right to receive medical treatment and to force physicians to provide it,” Cook Children’s added. “But even when a hospital or physician is a state actor, no right to medical treatment has ever been recognized outside the narrow context of prisons and other custodial settings.”

Gary W. Floyd, MD, chair of TMA’s Board of Trustees, says from his own experience that the ethics-committee process works. (He is on the staff part-time at Cook Children’s but is not involved with the hospital’s ethics committee.)

Dr. Floyd previously served as chief medical officer at a county hospital. There, “our ethics group was not the same group each and every time,” he said. “We took great pains to make sure that whoever was on that group did not directly care for that patient. … We had clergy members, we had businesspeople, we had laypeople who were respected in the community. It was almost like a jury of peers. It wasn’t all medical. A lot of the committee was nonmedical.”

The appellate court’s decision, on the other hand, “limits [physicians’] ability to use their professional opinion and medical ethics, and I certainly would be against that,” he said. “I don’t think the state should intervene there.”

Medical integrity at stake

Medicine agrees. The appeals court’s view “is that an ethics committee should be ignoring medical ethics,” TMA wrote in the joint friend-of-the-court brief urging the Supreme Court to reverse the lower court ruling. “This troubling aspect of the court of appeals’ ‘state actor’ analysis threatens the integrity of the medical profession and the robust ethical identity of many of Texas’s large hospital systems.”

A total of 20 organizations signed on to the brief with TMA, TAPA, and THA, including the American Medical Association (AMA); the Texas Pediatric Society; and the Texans for Life Coalition.

TMA also contends that the ruling, if left standing, would void the Texas Legislature’s ability to amend or revise the Advance Directives Act. If private physicians and hospitals are designated as “state actors,” the “looming prospect of due-process claims could make it impossible to achieve any real certainty or predictability by fine-tuning” the law, TMA’s brief says. And treating physicians as state representatives would conflict with “giving weight to medical ethics or matters of conscience.”

In passing the Advance Directives Act, the legislature allowed physicians “to refrain from making a directed course of medical intervention that violate[s] their conscience or sense of medical ethics, while providing the patient with a reasonable opportunity to transfer to another medical provider,” TMA wrote.

But the appeals court’s decision brushes those ethical concerns aside, according to TMA’s brief. The court is essentially saying, “if physicians and ethics committees are ‘state actors,’ then their own ethical concerns should not weigh in the decision,” the brief states.

In fact, TMA and the other organizations say in the brief, the appeals court’s decision “needlessly casts doubt on whether physicians are ever authorized to follow advance directives” and also casts doubt on the required notice to patients and families about the right-to-transfer process. If the appeals court had correctly decided the issue of whether physicians and ethics committees were state actors, TMA wrote, the court would not have needed to discuss issues with TADA at all.

“Making life-and-death decisions forever”

The Cook Children’s decision comes less than a year after TMA helped preserve the ethics-committee law against another high-profile challenge. In that case, the mother of a patient who died while on life-sustaining treatment unsuccessfully sued Houston Methodist Hospital, alleging a violation of due-process rights. (See “Preserving Do No Harm,” February 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 22-23, www.texmed.org/donoharm.)

In both cases, TMA maintains that the proper place to revisit TADA is the Texas Legislature, not the courts. But TMA says the appeals court’s decision in Cook Children’s “will cause confusion so long as it remains the last word – or for many of these statutory issues, the only word in Texas caselaw – about what key parts of the Texas Advance Directives Act mean and whether they are effective to serve their essential purpose.”

As of press time, the Supreme Court had not decided whether to review the case.

“Doctors have been making life-and-death decisions forever, before 1999 pre-TADA, since 1999 post-TADA,” Dr. Fine said. “It seems to me [the court’s] logic would make doctors, anytime they’re making a life-and-death decision of any sort, a state actor: in the operating room, in the emergency room.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(11):43-47

November 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page