Ever since COVID-19 grabbed the world’s attention in early 2020, the hopes for containing it have rested largely on safe, effective vaccines.

As they become ready, these vaccines should be a “game changer,” said John Hellerstedt, MD, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS). He was speaking in a joint video released in October with Texas Medical Association President Diana Fite, MD.

The video urged physicians and medical facilities to enroll in the DSHS Immunization Program in order to receive doses of and administer COVID-19 vaccines. (See “Sign Up Now to Provide COVID-19 Vaccines,” page 30.)

“It’s the thing that will break the back of COVID-19 and allow us to go forward to a better future,” Dr. Hellerstedt said in the video.

As of this writing, no COVID-19 vaccine had been licensed in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration. Health authorities said one could be approved as early as November.

But even though these vaccines are closer than ever to use by the general public, many questions remain about how they will be distributed to Texas physicians – and how they’ll be received by Texans.

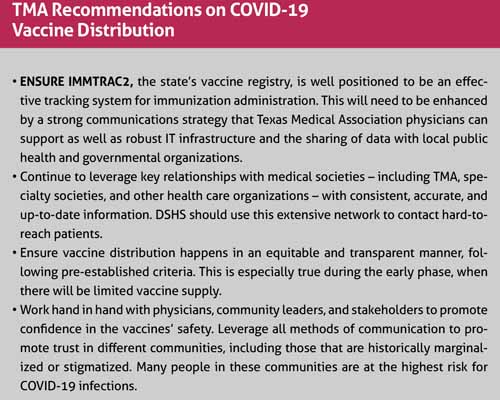

That’s why TMA in October weighed in on the state’s distribution plan with recommendations to help ensure COVID-19 vaccines are not only distributed effectively and efficiently, but also seen as trusted tools in the fight against the illness. (See “TMA Recommendations on COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution,” page 28.)

The state’s vaccine registry, ImmTrac2, also will play a vital role.

“It’s hard to predict how it will go,” said David Lakey, MD, a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force and vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer for The University of Texas System. “Aside from the logistical challenges, there’s making sure there’s equity – making sure there’s a thoughtful process and that [the vaccines] are used wisely and in an equitable way.”

That may be difficult in part because of growing public skepticism about COVID-19 vaccines. Only 42% of Texans said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to an October poll by the UT/Texas Politics Project, down from 59% who said the same in June.

The skepticism has been fueled by the fact that COVID-19 vaccines are being produced at record speed, says Charles Lerner, MD, an epidemiologist and infectious diseases physician in San Antonio who is a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force. (See “Our Best Shot,” November 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 16-21, www.texmed.org/BestShot).

Also, many people are concerned that the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which oversee vaccine production and safety, have bowed to political pressure to approve the vaccines quickly, he says.

Physicians are best equipped to address skepticism and convince people to take a vaccine that has been proven safe and effective, says John Carlo, MD, the former medical director for Dallas County Health and Human Services and past chair of the Texas Public Health Coalition.

“At the end of the day, that is the biggest challenge [for vaccine distribution],” he told Texas Medicine.

But conquering that initial skepticism will probably just be the start of a long educational process, he says.

“The other thing is that [the vaccine] may not be at more than 50% effective. And you only need a few people to say, ‘Hey, I got this vaccine and I still got sick,’” Dr. Carlo said. “There’s an opportunity [with the vaccine] to turn the corner. But there’s also a real concern that if this fails at any one step – and there are many steps we need to take – that we’re going to be farther behind [in reducing illness caused by COVID-19].”

Texas’ distribution plan

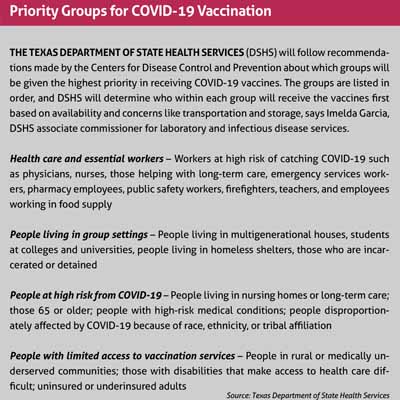

During a virtual public meeting of the DSHS Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response in October, the agency laid out a four-phase timeline for COVID-19 vaccine distribution that prioritizes those most in need of immunization, says Imelda Garcia, DSHS associate commissioner for laboratory and infectious disease services. (See “Priority Groups for COVID-19 Vaccination,” page 30.)

• Phase 1 – Limited access to the vaccine means few people – mainly targeted health care and emergency workers – receive doses.

• Phase 2 – Broader access allows wider distribution to priority groups and to other parts of the public.

• Phase 3 – Excess supply allows for broad vaccination.

• Phase 4 – Vaccination becomes routine.

DSHS plans to reach Phase 4 by the end of 2021, but there’s no way to tell how fast Texas will hit each milestone because so much depends on unknown factors, including which vaccines will work best, how much supply will be available, and how difficult the vaccines are to store and transport, Ms. Garcia says.

Dr. Hellerstedt named a panel of 16 Texas lawmakers, officials, and physicians – including Dr. Lakey and six other TMA members – to advise him on how to distribute COVID-19 vaccines. (See Rounds, page 8.) TMA Director of Public Health Christina Ly, PhD, also serves as a consultant to the panel.

Texas typically gets about 10% of national vaccine allocations through the Texas Vaccines for Children program, Ms. Garcia says. DSHS assumes the state will receive a similar allocation for the COVID-19 vaccines, but the size of the national COVID-19 vaccine supply Texas will be drawing from remains unclear.

“The biggest questions we have [are about the quantities of the vaccines],” Dr. Hellerstedt said. “We have no idea what quantities there will be at first.”

In Phase I, priority should go to physicians and other health care professionals who face the biggest professional risks because of COVID-19, like those who work in emergency departments, Dr. Carlo testified to the task force on behalf of TMA.

“Considerations should also include prioritizing high-risk workers, such as geriatricians or intensive care unit physicians, who care for patients who are over 65 years of age, obese, diabetic, or immunocompromised and have a higher risk of severe complications with COVID-19,” he told the task force.

Based on what happened during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, distributing vaccines to physicians, other health care professionals, and emergency workers is likely to present few problems, Dr. Carlo says. But difficulties could arise when distributing them to people in the priority levels after that – those living in group settings and patients at the highest risk for infection.

“Basically what [could] happen is that you’ll have a long line of people who are not in those priority groups who are going to want the vaccine, and then you’re going to have trouble finding those who are in the priority group to stand up and get the vaccine,” he said. “And then, you have to ask the question: Since I have the shots, what do I do?”

Leveraging ImmTrac2

In addition to equitable distribution, TMA’s recommendations to the task force focused on leveraging community relationships to communicate and promote confidence in the vaccines’ safety and contact hard-to-reach patients, while bolstering resources for and information about ImmTrac2, the state’s vaccine registry.

Typically, only pediatricians and physicians who regularly give vaccines are registered with ImmTrac2. However, state law mandates that vaccines distributed because of natural disasters or public health emergencies must be recorded in the registry, Ms. Garcia says.

Most COVID-19 vaccines in development will require two doses spaced about two to three weeks apart. That will make ImmTrac2 a vital tool for physicians and patients as they keep track of doses, Dr. Lakey says. ImmTrac2 records also can ensure both doses are from the same manufacturer, an important safety step, he says.

COVID-19 will be a test for ImmTrac2, Dr. Carlo says. The registry will help keep track of doses, but it also is needed to keep track of the geographic distribution of the vaccines.

“There’s going to be a high degree of need for reporting that I don’t think we’ve ever really tried to do before [with ImmTrac2],” he said.

TMA’s recommendations to the task force also called for ensuring equity in vaccine distribution and reaching out to communities that are “historically marginalized or stigmatized.” That outreach will be especially important in the Black and Latino communities, Dr. Carlo says.

And while physicians play an important role in educating the public about vaccines, community leaders will be needed to amplify messages about vaccination in these communities, he says. “Distrust of the medical community and treatments have long been documented in minority populations,” Dr. Carlo said. “TMA encourages [DSHS to] plan to prioritize countering the distrust by developing culturally

and language-appropriate messaging, using community champions and health workers, as well as tying in the voices and expertise of the physicians these communities do trust.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(12):26-31

December 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page