Physicians already have stringent regulations to follow to protect patient privacy – you know, those HIPAA regulations that lay out dozens of hot coals for doctors to avoid.

But in the evolving world of health information technology, some vendors that store and transmit health information – such as the tech minds behind certain mobile apps – are getting their hands on patient data without any HIPAA leash to rein in their use of it.

Now, organized medicine is doing its part to preserve patients’ privacy when their health information finds its way outside of HIPAA-covered organizations. In May, the American Medical Association (AMA) released a detailed set of Privacy Principles that it believes should apply to those groups.

The principles will “serve as the foundation for AMA advocacy on privacy,” the association says in the document’s preamble. They’re meant “to ensure that as health information is shared – particularly outside of the health care system – patients have meaningful controls over and a clear understanding of how their data is being used and with whom it is being shared.”

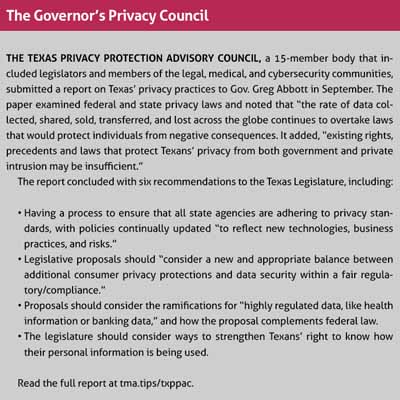

Joseph Schneider, MD, chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Health Information Technology, called the move “an excellent start” to addressing the many privacy concerns that exist with patient data and third parties. He was a member of the Texas Privacy Protection Advisory Council, which submitted a report to the governor in September with recommendations for improvement to privacy practices in Texas, saying, “existing rights, precedents and laws that protect Texans’ privacy from both government and private intrusion may be insufficient.” (See “The Governor’s Privacy Council, page 23.)

Similarly, “the concept of the AMA Privacy Principles is not something that we know that we can do today. It’s really, ‘What should we be striving towards?’” Dr. Schneider said.

“The volume of digital patient data that falls outside current federal privacy laws merits serious attention by policymakers,” Fort Worth immunologist Susan R. Bailey, MD, AMA’s president, told Texas Medicine in a statement. Once social media platforms and tech companies have their hands on that sensitive information, she added, they can use it “for marketing and other dubious practices.

“Data brokers are scooping up this data, combining it with other consumer information (such as location and shopping patterns), and creating patient profiles that can lead to discrimination,” Dr. Bailey said. “Our country needs clear guardrails on data use, or we’ll continue to see an erosion of public trust that will undermine the potential for digital health.”

“Responsible stewards”

AMA makes clear it’s not proposing additional regulations on physicians and other HIPAA-covered entities.

Instead, AMA says the principles “shift the responsibility from individuals to data holders” not covered under HIPAA. The third parties who access someone’s private health information, AMA adds, “should act as responsible stewards of that information, just as physicians promise to maintain patient confidentiality.”

The principles are divided into five sections: Individual rights, equity, entity responsibility, applicability, and enforcement. Some examples of each include:

Individual rights – The right to know which data an organization is “accessing, using, disclosing, and processing” at or before the point of collection; the right to control how organizations use and disclose that data; the right to tell entities not to sell or otherwise share their data; and the ability to “protect and securely share pieces of information on a granular, as opposed to a document, level.”

Equity – Protection from “discrimination, stigmatization, discriminatory profiling, and exploitation” when data is collected and processed, or resulting from using and sharing the data, “with particular attention paid to minoritized and marginalized” communities. Also, privacy frameworks must advance policies “to benefit individuals of all income levels. For example, the AMA would not support a policy in which paid apps provided greater privacy protections than free apps.”

Entity responsibility – Entities should collect only “the minimum amount of information needed for a particular purpose,” and should be required to disclose to people what specific data they collect, for what purpose, how often, and with whom they’re sharing the data.

Applicability – Privacy legislation should apply to any “entities that access, use, transmit, and disclose data, including HIPAA business associates”; and the legislation should be adaptable to many different organizations, uses, technologies, and sectors, and scalable to organizations of all sizes.

Enforcement – Individuals shouldn’t be responsible for costs of enforcement unless they’re pursuing a private action of their own, such as a lawsuit; and the Federal Trade Commission should be granted authority to define unfair data processing practices, as well as the minimum data needed for particular purposes.

Dr. Schneider emphasized the importance of patients being able to control their data on a “granular” level – that is, picking which pieces of information are shared with whom.

For instance, right now, an electronic medical record, “has a lot of information that a physician might need to share with a specialist. But it might contain data that are extremely personal that the patient doesn’t want shared,” he said. “The ability of the patient to easily tag pieces of information and designate, ‘I want that shared, but I don’t want that shared, and I want this shared, but don’t share this,’ is going to be important in the future.”

Tex Med. 2020;116(12):22-23

December 2020 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page