Texas physicians who give shots regularly are used to dealing with vaccine hesitancy – patients reluctant to get a flu vaccine for themselves or a whooping cough shot for their kids. That reluctance has contributed to a steady decline in the state’s vaccination rates among young people in the past two decades.

Comparatively, however, the hesitancy surrounding COVID-19 vaccines is off the charts. Only 51% of U.S. adults say they would definitely or probably get a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 if one were available today, a drop from 72% in May, according to a September survey by the Pew Research Center (tma.tips/PewCovidSurvey).

The survey found that a top concern is the speed with which the COVID-19 vaccines are being developed. Vaccines typically take 10 to 15 years to reach the public, and the previous fastest time was set in the 1960s, when the mumps vaccine took about four years.

(See “Our Best Shot,” November 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 16-21, www.texmed.org/BestShot.)

The speediest COVID-19 vaccines are racing to the public in less than one year, and even people who typically support vaccines are concerned that there might not be enough evidence that they are safe and effective, says Austin pediatrician Ari Brown, MD.

“For other vaccines, it takes years to get it out on the market, so you have years of data to follow those patients [who received the vaccine], and we don’t have that” for COVID-19, she said. “There is going to be a little bit of holding our breath” to see the full impact of these vaccines, she added.

At this writing in late November, three vaccines – those produced by Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca – were expected to reach the public by early 2021. Physicians must soon be ready not only to provide COVID-19 vaccines but also to explain why people should take them, says Lois Ramondetta, MD, a gynecological oncologist at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and a member of the Texas Medical Association Council on Science and Public Health.

In these conversations, “the biggest pitfall is to assume that someone is going to want to do it and even that they understand why it’s important,” she said.

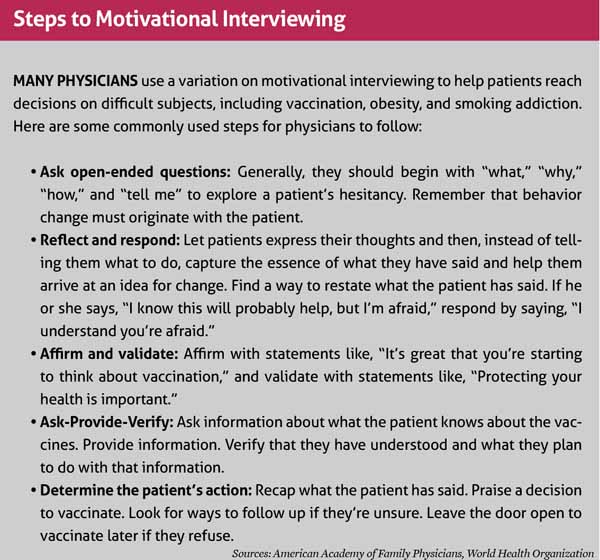

Pediatricians, family physicians, and other doctors who administer vaccines regularly use tools like motivational interviewing to help encourage higher participation. (See “Steps to Motivational Interviewing, page 44.) Though COVID-19 and its vaccines are new, those same tools will be just as important, Dr. Brown says.

“We have the template for assessing those communications about vaccines,” she said. “And I think that most of the things that we’d say [about childhood vaccines] are absolutely applicable here.”

Motivational interviewing will help physicians counsel patients face to face, says Trish Perl, MD, chief of the infectious diseases division at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and a member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force.

But ending the problems caused by COVID-19 also will require broader public education by physicians as well as counseling in the exam room, she says.

“Sometimes [vaccine hesitancy is] just a lack of knowledge,” Dr. Perl said. “I find a lot of people just don’t know, and if you give them the facts, they’re fine.”

Getting on the same page

Physicians – along with first responders and essential workers – will be among the first groups to receive the COVID-19 vaccines, according the distribution plan developed by the Texas Department of State Health Services. (See “Operation Distribution,” December 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 26-31, www.texmed.org/OperationDistribution.) Assuming there’s strong evidence that the vaccines are safe and effective, most physicians likely will take them right away while others will wait longer before taking that step, Dr. Perl says.

“We have to walk into this knowing that not everybody’s going to be on the same page,” she said. “It’s going to be our challenge to convince them. Some people are more cautious and they’re going to want to see more data before they’re comfortable.”

While most physicians don’t have the background to determine a vaccines’ safety and effectiveness on their own, they can follow the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which sets the guidelines for immunization use for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says Charles Lerner, MD, a San Antonio infectious disease specialist and member of TMA’s COVID-19 Task Force. (See “Talk to Patients about ACIP,” October 2020 Texas Medicine, page 46, www.texmed.org/WhatIsACIP.)

“These are reasonable people [at ACIP],” he said. “They keep looking at data and making rational decisions.”

Once the COVID-19 vaccines become available, even many physicians who are not used to giving shots will be expected to administer them, Dr. Brown says. While physicians should counter vaccine hesitancy with facts and information, some of the most effective techniques aim for patients’ emotions rather than their intellects.

“When it comes to childhood vaccinations, what I say is that I give these vaccines to my own children and I wouldn’t do anything differently for yours,” she said.

Physicians offering COVID-19 vaccines can make a similar appeal to emotion because most already will have taken the vaccine themselves, Dr. Brown says.

Physicians can tell their patients, “‘You trust me as a [physician], you trust my advice, and this is what I do personally,’” she said. “It’s very powerful. You can talk all the science you want with people, but that’s usually the argument that sticks.”

It’s also important to find common ground with patients, she says. Since most people have been unhappy with pandemic-related dangers and restrictions, that’s a great way to connect, Dr. Brown says.

“We can all agree that we would like to get back to life as usual,” she said. “And what we know is that the quickest way to get back to that is to get vaccinated, not just let everybody get the disease.”

Back to “normal?”

While a COVID-19 vaccine will be a huge step toward returning to some sense of normalcy, patients must understand that getting a shot does not mean they can throw away their masks and return to pre-pandemic behavior, Dr. Perl cautions. Many unknowns still will remain, for example how long the vaccines give immunity and whether vaccinated people can still spread the disease, she says.

“I don’t think it’s clear [to the public] that it’s going to take a long time to vaccinate all these people,” she said. “Also, we’re going to have a large group of people who aren’t going to be convinced [to take the vaccine] for a while.”

Physicians may find it hard to be understanding with patients who refuse a vaccine, especially if their justifications are based on unfounded rumors or conspiracy theories, Dr. Brown says. But it’s vital that physicians avoid alienating patients by getting angry or acting judgmental.

“[Physicians] can only advise,” she said. “And whatever that patient decides to do, that’s ultimately their responsibility. So being respectful is probably going to gain you more mileage when they go home and think about it rather than having a negative interaction in the office.”

Taking a wait-and-see approach can pay off long term, she adds. “It doesn’t work for everybody, and sometimes it takes time and it takes several conversations.”

Physicians should educate people outside the exam room as well, Dr. Perl says. That starts by working with political leaders at all levels to present a unified front about the need to vaccinate.

“Part of the problem with COVID is all the mixed messaging the public has gotten,” she said. “If we can align the message in the public health community and the medical community with government, it’s going to really help people gain a little more trust in what we’re saying.”

Physicians can use social media, email newsletters, and traditional media like TV and newspapers to notify their patients and their communities about how they feel about COVID-19 vaccines, says Dr. Brown, who also is an author and appears frequently on national news shows.

This outreach does not have to involve cheerleading for vaccines, she says. A newsletter that neutrally describes scientific findings on COVID-19 vaccines can be informational while also keeping the subject in people’s minds.

“You know it’s coming,” she said. “So start having these conversations now, even if your patients aren’t going to get their vaccines until April or June.”

Tex Med. 2020;117(1):42-44

January 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page