Not long after COVID-19 hit Texas last March, pediatricians at Austin Regional Clinic (ARC) began screening patients for food insecurity. The timing was coincidental but fortunate given the pandemic’s economic toll, says Austin pediatrician Sangeeta Jain, MD.

During a recent exam, she asked a mother in her mid-30s the now routine screening questions on hunger. (See “Hunger Vital Signs,” page 23.)

“The room went quiet and [the patient] said, ‘I’ve never been in this position before,’” Dr. Jain recalled. “‘I’ve always worked, and I’ve always had health insurance, and I’ve always had enough food.’”

But the woman’s family was facing hard times. She could no longer work because of complications from her latest childbirth, and she now had two children to care for. Meanwhile, her husband was getting less work.

“She was fighting off tears, and she said, “It’s really been tough,’” said Dr. Jain, who is chair of pediatric clinical quality at ARC.

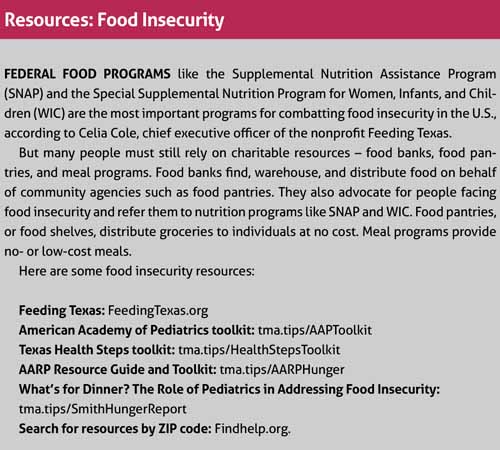

Fortunately, Dr. Jain was able to direct that mother to local resources that could help. But food insecurity often goes unrecognized among Texans – and the problem is getting worse because of the pandemic, says Celia Cole, chief executive officer of Feeding Texas, a nonprofit that works with 21 member food banks to form the state’s largest hunger-relief organization.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines “food insecurity” as a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. In early 2020, before COVID-19, statistics compiled by USDA estimated that one in seven Texans and one in four Texas children faced food insecurity, Ms. Cole says. (See map, page 25.)

“And then the pandemic hit, and now we’re estimating that one in four Texas families is struggling with food insecurity,” she said. “We’re talking about between 8 million and 9 million Texans. And unfortunately, the rate of food insecurity is higher among communities of color, in rural communities, and among families with children. It’s always been a significant concern to Texas, and now it’s an even bigger one.”

Physicians typically help patients facing food insecurity in three ways, Ms. Cole says: screen patients and write prescriptions for food to be provided by a local food bank; work with food banks to make food available to patients in the office; and use their offices as a place to educate the public about food through cooking or food classes.

Efforts to tackle food insecurity in the exam room are welcome, says Valerie Smith, MD, a pediatrician in Tyler, in East Texas. But it remains a broad social problem, and physicians need to push for greater community buy-in to find ways to address it.

Dr. Smith founded the Smith County Food Security Council, which brings together representatives from schools; public health; the Women, Infants and Children program; health care; businesses; and farming to coordinate efforts at easing hunger.

And there are plenty of ways for physicians to get involved. For instance, each of Texas’ 21 regional food banks have boards, and only two physicians – Dr. Smith and one other doctor – sit on those boards, she says.

“We need health care professionals who know and understand our patient population to be at the table when people are making decisions about programs where money is being spent to feed our communities,” she said.

Diagnosis and prescription

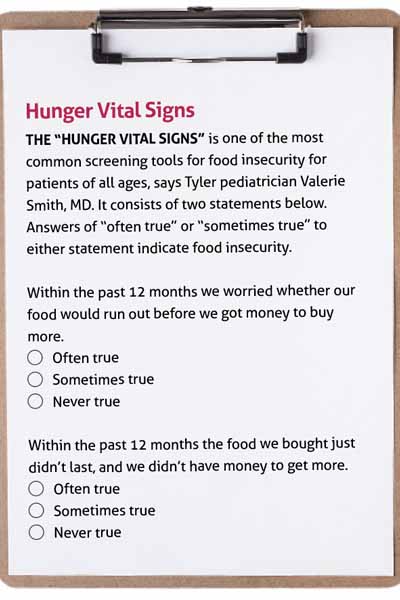

Screening is the most effective way physicians can diagnose hunger among patients, and the two-question “Hunger Vital Signs” screen can help identify those in need, says Marjan Linnell, MD, a pediatrician at ARC in Kyle and co-chair of the Committee on Nutrition and Health for the Texas Pediatric Society.

ARC began screening as a larger move to address social determinants of health, she says. For example, food insecurity underlies a range of serious health issues, including low calcium, low vitamin D, and tooth decay. Later in life, it also can worsen chronic illnesses such as hypertension and cancer, according to the USDA (tma.tips/HungerChronicIllness).

Food insecurity affects children’s health indirectly as well, Dr. Linnell says. For instance, a physician might prescribe an asthma inhaler for a child, but “if [parents] can’t feed their kids they’re not going to spend even $4 to buy one.”

Screening for food insecurity works best if it’s coupled with direct resources physicians can refer patients to, says Natalie Poulos, PhD, a research associate who specializes in food insecurity at The University of Texas Health Science Center in Tyler.

“Studies point to hesitancy to screen for food insecurity [among physicians], not because they don’t want to but because they don’t feel they have the resources,” she said. “If we encourage them to screen for food insecurity, we also have to provide a clear path for good referrals to community organizations.”

That’s not always easy. In many cases, the nearest food bank is across town or even several counties way. Also, many people with food insecurities live in “food deserts” – areas without access to healthy foods. Paradoxically, these people often struggle with obesity because high-calorie processed foods tend to be cheaper and more available than fruits and vegetables, Dr. Jain says.

Many food banks and pantries have only recently come to understand that people don’t just need food but the right kinds of food, says Dr. Smith, who obtained a master of public health degree focused on food insecurity. Before referring any patient to a food bank or pantry, physicians should establish a relationship with those running it to ensure patients will get the types of food they need.

“Physicians want to know if they refer a diabetic patient to a food pantry that they will get the healthy foods they need to help address their disease,” she said.

One solution for physicians is to write prescriptions for healthy food at a specially designated food source. A Harris County pilot program used food prescriptions at three clinics where food insecurity was high, according to a September 2019 study in Translational Behavior Medicine. The prescriptions were redeemed at a specific food pantry that resembled a small grocery store to reduce the stigma associated with donated food.

The study reported a 94.1% drop in the prevalence of food insecurity among patients. It also found that 99% of participants said they ate all or most of the food provided. Both health care professionals and participants felt the program was “well received and highly needed,” study authors wrote.

In 2018, St. Paul Children’s Clinic, where Dr. Smith works, partnered with the East Texas Food Bank and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler to launch “Partners in Health” in Smith County. Nearly one-fifth of people there lived with food insecurity before the pandemic, according to USDA data, and their numbers have grown since COVID-19 appeared, Dr. Smith says.

Physicians at her clinic currently screen patients for food insecurity, and those who qualify get 12 weeks of shelf-stable food as well as nutrition education, she says. Even before the program started, her clinic had a food pantry on site, which helped her understand how best to work with fellow physicians as other clinics joined the program.

“The [East Texas Food Bank] didn’t know anything about clinic workflow and barriers and how clinics typically screen,” she said. “So we’ve been able to provide a lot of insight and technical assistance so that additional clinics can start taking part in the partnership.”

Avoiding long-term problems

Dr. Smith frequently speaks to Texas physicians about food insecurity, and most welcome the opportunity to help, she says. But there is a gap – created by differences in education, culture, and income – between many physicians and the patients most likely to be food insecure, and that gap can lead to misunderstandings.

“[Physicians should] understand that most families who are food insecure are working and their food insecurity is a short-term problem,” she said. “But it can lead to long-term poor outcomes if we don’t do something about them.”

No matter the typical income level of their patients, physicians should always assume that some of their patients face hunger, Dr. Linnell says. When more than 70 pediatricians at 20 ARC clinics across the Austin area began screening, most of the clinics found people who were food insecure, she says.

“There are many [doctors] who think, ‘This isn’t happening to my patients,’” she said. “If you’re not asking about it, you don’t know about it. But I promise you regardless of how well off your patient population is, there is at least one [person] who is in a food insecure household.”

Physician practices that do a good job of confronting food insecurity designate one staff member – a physician, nurse, or staff worker – as a point person to make sure everyone has buy-in and that details are addressed, Ms. Cole says. That usually means ensuring screenings take place or that food and educational programs remain available to patients.

In this year’s Texas legislative session, physicians could help boost screenings by lobbying lawmakers to make sure Medicaid and other health insurance providers pay for those screenings, Dr. Linnell says.

“If we could get reimbursed for food insecurity screening, a whole lot more people would be doing it,” she said.

The Texas Medical Association has several other legislative priorities designed to increase Texans’ access to healthy foods and decrease their risk of obesity:

• Fully fund the Surplus Agricultural Products Grant, which ensures food banks have the produce to keep Texans from going hungry during the pandemic. In October, the Texas Department of Agriculture proposed slashing funding for the program by 41%, or $1.9 million, this fiscal year as part of Gov. Greg Abbott’s call for 5% cuts from each agency, according to Feeding Texas.

• Encourage Medicaid managed care organizations to implement initiatives to address social determinants of health, including healthy food access.

• Increase access to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits for senior citizens by streamlining the application process.

Food insecurity costs Texas a lot of money each year, according to a 2016 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Texas paid $6 billion in health care costs tied to food insecurity that year, just behind California at $7 billion, CDC found. Individually, food insecure adults in the U.S. face annual health care costs that are $1,834 higher than those of people with enough food (tma.tips/CDCHungerStudy).

“I feel like we’re at step 1.1 of 1 billion,” Dr. Linnell said. “Every day I feel good that we did something, and the next [day] I think, oh man, so much work still to do.”

Tex Med. 2020;117(2):22-25

February 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page