Before March 2020, remote patient monitoring (RPM) was a tool endocrinologist Thomas Blevins, MD, used to help patients with diabetes track and regulate blood sugar levels and report the results back to him.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic forced many doctors to turn to telemedicine, Dr. Blevins and the nine other physicians on staff at Austin Diabetes and Endocrinology had to rev up their RPM use. (See “The Tele-Future is Now,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 14-19, www.texmed.org/TelemedFuture).

“Nowadays, during COVID, we’re doing this much more routinely,” he said. “In fact, this morning, about three people who I saw had data that I could download – out of 10 or 11 [patients]. I can see what’s going on day to day. I can discuss it with them. I can make treatment decisions very efficiently.”

RPM technology allows patients and physicians to monitor symptoms and make treatment changes based on real-time information. It ranges from digital blood pressure cuffs to voice apps that remind patients with diabetes, for instance, to take their insulin.

But it can also be relatively low-tech, Dr. Blevins says. Patients who aren’t comfortable using computers and smartphones can fax in their blood sugar data.

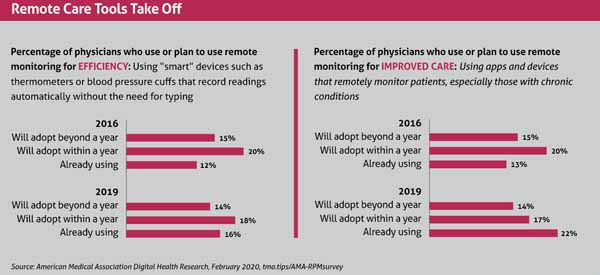

RPM devices are becoming more sophisticated, and even before the pandemic, a growing number of physicians were turning to the remote technology. Even pre-pandemic, the number of physicians using RPM designed to improve patient care rose to 22% in 2019 from 13% in 2016, per an American Medical Association survey released in February 2020. (See “Remote Care Tools Take Off,” page 41.)

A 2018 AMA survey had found that cardiologists, nephrologists, and neurologists used RPM most frequently. But RPM devices can help treat a wide variety of conditions, including asthma, hypertension, diabetes, dementia, substance abuse, weight gain or loss, and infertility.

In the absence of more recent data since the pandemic began, anecdotal evidence indicates that Texas physicians’ use of RPM has spiked along with their use

of telemedicine, says Yvonne Mounkhoune, practice management quality consultant at the Texas Medical Association. That includes a rise in the number of physician queries TMA has received on RPM.

“The biometric data [from RPM devices] makes the physician feel a little more comfortable with their diagnosis or the recommendation they’re going to make to the patient on the screen,” she said.

Physician practices will have to adapt to accommodate the new technology, Dr. Blevins says. For instance, health professionals and patients must get trained, and one staff person at each of his clinics manages the data from patient devices. Before the pandemic that wasn’t necessary, he says.

But like telemedicine, increased RPM use is here to stay, he says.

“It’s what people want. It’s what many of our patients expect. I think it’s what we expect – having devices at home that can send information and having the technological ability to send information. It’s common now.”

Revving up

The surge in the use of RPM devices has been helped along by recent regulatory changes.

In 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded hospitals’ and health care groups’ ability to get paid for using remote patient monitoring. In 2020, CMS further eased payment restrictions on the use of RPM devices during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Medicare pays relatively high rates for prescribing RPM devices, and many private insurers have followed its lead, Ms. Mounkhoune says.

To get started, practices should decide what types of remote patient monitoring services patients need and then match that with the available technology, Ms. Mounkhoune recommends. In many cases, that can be straightforward when the technology is simple or well-established.

For instance, sudden weight gain can be a sign of worsening congestive heart failure, she says. Patients may track that weight in part using a store-bought scale and report the data back to the practice by phone, email, or some other traditional means.

In those cases, practices typically can handle RPM management themselves.

Some practices have enough tech-savvy staff to administer even complicated RPM systems. But more sophisticated devices and reporting procedures often must be handled by third-party vendors, says Lee Ann Pearse, MD, a pediatric cardiologist in Dallas for 30 years.

“We’ve always worked with [cardiac] event monitoring companies for as long as I’ve been practicing,” she said.

Some vendors require physicians or patients to pay for devices upfront, while others lease the devices or incorporate the cost of the devices into their fees, Ms. Mounkhoune says. Physicians should ask important questions about how the vendor’s equipment meets patient needs and how well it works with a practice’s existing technology, such as electronic medical records.

However, payers often require physicians to use preferred devices, Dr. Pearse adds.

And some of the biggest questions physicians have about RPM devices concern liability, Ms. Mounkhoune says.

Fifty-seven percent of physicians list medical liability insurance coverage of digital health tools like remote monitoring as “very important,” according to the AMA survey.

Sidney Ontai, MD, a Victoria family medicine physician and former chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Practice Management, helped pioneer telemedicine in Texas. However, a few years ago, he backed away from an RPM program because patients would be reporting health data around the clock and his staff would not be available to receive and react to the information deluge if an emergency arose.

Because his practice could be legally liable if something happened to a patient as a result, “that soured me on it,” Dr. Ontai said.

Some physician practices hit this issue head-on by working with a company that monitors the patient’s data and can communicate with the physician and patient. The vendor Dr. Pearse uses monitors cardiac data 24/7 and notifies her practice if a patient’s heart data shows anything of concern.

Dr. Blevins’ practice takes a different approach. Some of his patients’ RPM devices provide alerts if their blood sugar spikes too high or drops too low. But the warnings go directly to patients, not to physicians or the practice. Instead, patients are educated to respond quickly when readings require urgent medical attention.

Dr. Blevins says the practice does not have the staff to respond individually to each alert.

“If we did, that would be an issue because we’d have to be monitoring thousands of trackings and events,” he said.

Getting technical

Practices using remote monitoring devices also must take precautions against hackers, who frequently attack technology systems like medical devices that are left unprotected in order to disrupt care or install ransomware. That scenario was regarded as the U.S.’s No. 1 health technology hazard in a 2019 report by the ECRI Institute, a Pennsylvania nonprofit that studies safety issues in health care (tma.tips/ECRIreport).

In many cases, RPM vendors take on the responsibility of protecting their systems. But medical practices running their own RPM systems should follow best practices, according to ECRI.

“Safeguarding assets requires identifying, protecting, and monitoring all remote access points, as well as adhering to recommended cybersecurity practices, such as instituting a strong password policy, maintaining and patching systems, and logging system access,” the report said.

Physicians planning to use RPM devices also must prepare to roll with the occasional technical glitch, Dr. Blevins says.

“Sometimes websites go down, and then we can’t get the information [from the patient],” he said. “Other times people have difficulty downloading [their data] for one reason or another because of equipment they have or because the website’s not working.”

Patient inexperience or technical problems often cause these glitches, Dr. Blevins says. “People don’t have to be really technically savvy,” he said. “But there are people who don’t have smartphones [for downloading data], a good internet hookup, or the type of computer they need – or even a computer.”

Physicians also should keep in mind that patients may not be comfortable wearing a device, Dr. Pearse says. That is especially true for younger patients. Sometimes the monitors are bulky or cause skin irritation, or young people simply don’t want to wear them, she says.

In those cases, she encourages the family to use a Fitbit or smartwatch as a monitor. The data is not as reliable, but it’s better than nothing, and she gets higher compliance from young patients.

Tex Med. 2020;117(3):40-43

March 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page