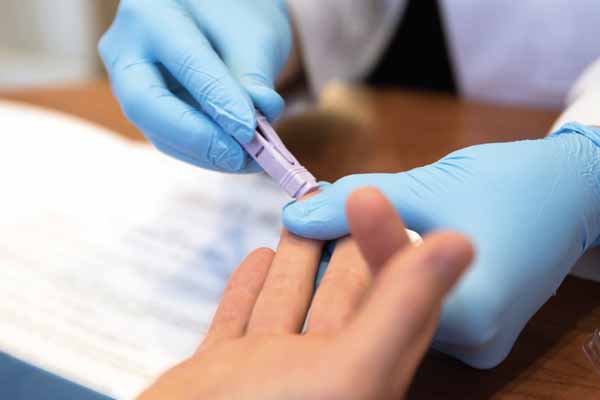

Testing is one of the best ways to combat HIV infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine testing for patients between the ages of 13 to 64.

Yet, fewer than 40% of eligible people have ever had an HIV test, according to a 2019 CDC study.

“Everyone should get a once-in-a-lifetime HIV test, and it’s not getting done,” says Thomas Kaspar, MD, a Victoria infectious disease specialist and member of the Texas Medical Association’s COVID-19 Task Force. CDC recommends annual testing for high-risk populations, including men who have sex with men.

Physicians can do more to make sure this vital testing happens, says John Carlo, MD, chief executive officer for Prism Health North Texas, president of AIDS Arms Physicians, and former chair of the Texas Public Health Coalition.

In many cases physicians don’t even realize that routine HIV testing is recommended, he says. Also, both physicians and patients frequently don’t understand that Medicare, Medicaid, and all types of insurance cover HIV testing either completely or at low cost to the patient.

“Payment’s not an issue, but people aren’t aware that’s there,” Dr. Carlo said.

Also, some physicians fear offending patients, he says.

“There is a general [idea that] this may not apply to my patient – I don’t really want to go there, I don’t want to take the time to talk about it because there’s kind of a stigma as well,” he said.

That problem goes far beyond Texas, according to a 2018 study in the Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (tma.tips/PhysiciansHIVTesting).

“Physicians are not routinely offering patients HIV testing, partly due to perceived patient discomfort with discussing HIV,” the study says.

To help physicians overcome such obstacles, TMA has created a poster designed to help patients understand that HIV testing is both necessary and routine. (See page 45 and visit www.texmed.org/HIVTestingPoster.) Physicians tend to have the most success in encouraging testing by discussing it as part of a comprehensive annual check-up, just like tests for hepatitis C and cholesterol, Dr. Carlo says.

“[It’s like] any routine laboratory test is part of an annual visit, and that’s how to describe it,” he said. “We’re just going to add this to the list of things you’re going to be tested for today.”

That approach tends to reassure patients, even those who might otherwise be reluctant to get an HIV test, Dr. Carlo says.

“Many believe they’re already getting it as part of their annual health visit,” he said. “I haven’t seen, if it’s presented in the correct way, any sort of pushback on getting the test done.”

How to Stop HIV

Testing remains a top priority for preventing the spread of HIV, according to CDC. An agency analysis found that the nearly 15% of people with HIV whose infections are undiagnosed account for 38% of all HIV transmissions in the U.S. (tma.tips/2019HIVanalysis).

Voluntary testing does identify many people who are HIV positive. But a large number of diagnoses come about because patients are required to take an HIV test, Dr. Kaspar says. For instance, Texas law requires pregnant women to be tested.

“About half of my new diagnoses are pregnant women who are forcibly tested and otherwise would not have been tested,” he said. “Not only does that get them treated to keep them from spreading it to someone else, it keeps their baby from being infected.”

In the 1990s, an HIV diagnosis was a death sentence because it inevitably led to AIDS. Many patients don’t realize that medicines developed since then, like fusion inhibitors, prevent HIV from becoming more serious, Dr. Kaspar says. Also, pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis can help keep the sexual partners of HIV patients from contracting the disease, he says. Likewise, newer medications prevent the transmission of HIV from pregnant mothers to their unborn children.

The number of Texans living with diagnosed HIV rose by 16% between 2013 and 2018, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. This was not because the number of diagnoses increased but because improved medications allow people with HIV to live longer, the agency says. (See “HIV in Texas, By The Numbers,” page 44.)

“In the year 2021, there’s no reason for anyone to die from HIV because testing leads to treatment and treatment keeps people alive,” Dr. Kaspar said.

The virus has hit some populations harder than others. Black Americans have suffered the highest HIV rates since scientists identified the U.S. epidemic in the early 1980s. Although Blacks represent only 12% of the U.S. population, they account for 43% of diagnoses and 42% of those living with the disease, according to CDC.

Stigma about testing helps feed the virus’ disproportionate impact on Blacks, along with factors like poverty, lack of access to health care, and lack of awareness about HIV status, CDC says.

Improving diagnosis rates is central to recent U.S. government initiatives to reduce HIV infections such as the “Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America” campaign, which calls for cutting HIV infections by 75% in five years and 90% in 10 years (tma.tips/EHE), and a presidential plan to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2025.

The U.S. government currently pays $20 billion in annual direct health costs for HIV prevention and care, according to HIV.gov. Improved testing is one of the most direct paths toward ending those expenses, Dr. Kaspar says. For instance, a 2006 CDC study found that people who realized they have HIV modify their behavior to reduce spreading the virus.

“[Testing is] a very simple and straightforward thing that would be very cost-effective,” he said.

Tex Med. 2021;117(4):44-46

April 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page