How does Texas get ready for the next pandemic?

The answer to that question is long and touches on many different aspects of health policy, says John Hellerstedt, MD, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services.

But the top priority is clear.

“I can honestly tell you that in preparing for the next pandemic, the thing we can’t do without is health literacy – and here I’m just talking about basic germ theory of disease,” Dr. Hellerstedt told the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Science and Public Health at Winter Conference in January.

Personal health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others,” according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

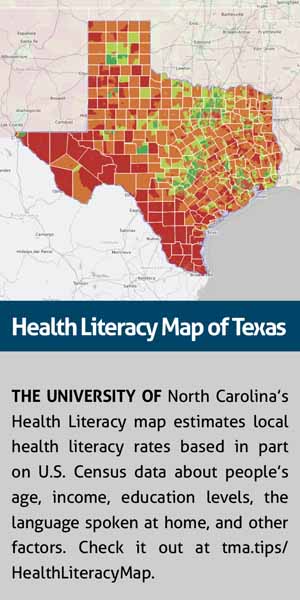

Individual health literacy can be shaped by a number of factors, including education, income level, age, ethnicity, race, and disability, says Eduardo Sanchez, MD, chief medical officer for prevention and chief of the Center for Health Metrics and Evaluation for the American Heart Association in Dallas. For instance, people with low incomes or less education tend to have lower health literacy.

They also may struggle with overall literacy. About 52% of U.S. adults age 16 and older had difficulty with everyday literacy tasks between 2012 and 2017, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (tma.tips/LiteracyStats).

So even apparently simple written directions may be difficult for some patients to follow, says Dr. Sanchez, who is a former DSHS commissioner.

“Understanding that is important,” he said. “But it’s also important to understand that a person with a degree in economics might not be as health literate as you [assume] they may be. [Physicians and their staffs] should assume lower health literacy and discuss health topics with that in mind.”

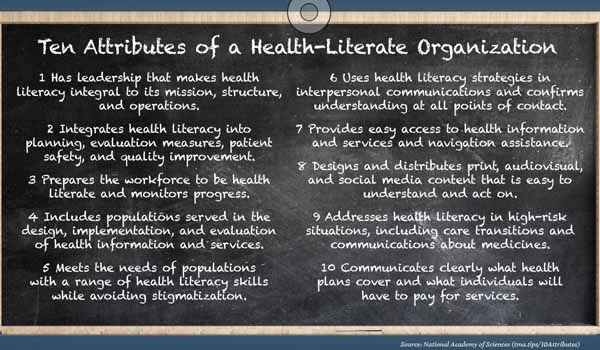

The ability to communicate with patients on their level is called “organizational health literacy,” which HHS defines as “the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.” (See “Ten Attributes of a Health-Literate Organization,” page 33.)

Health literacy affects all health problems, but COVID-19 has highlighted how badly it is needed, Dr. Hellerstedt says. For instance, many people still do not understand the need for face masks, physical distancing, hand washing, and other non-pharmaceutical interventions.

“The biggest breakdown to me was that people thought of [mask-wearing and other interventions] only as an individual prerogative that they had,” he said. “They didn’t see that their behavior affected other people and in fact, might endanger their life and their health. I think we could have had a more rational conversation if – based on the germ theory of disease – they understood … they might be perfectly healthy and they might be willing to take the risk of getting ill, but that decision had consequences for other people who wouldn’t have chosen to get sick.”

Health literacy’s importance goes beyond COVID-19, Dr. Sanchez says. It’s about building a perspective informed by scientific concepts that are explained in easy-to-understand terms. Physicians can promote health literacy in many ways, such as advocating for more health instruction in schools, supporting bills in the Texas Legislature that boost health literacy, and making sure their own offices communicate clearly with patients, he says. (See “The ABCs of Health,” page 36.)

Just last November, an organized push by TMA physicians became instrumental in getting the State Board of Education to approve new Texas curriculum standards that include more comprehensive and medically accurate instruction on several health-related topics (www.texmed.org/TEKS2020).

Ultimately, health literacy is about improving people’s health across the board by getting them to change their behavior in the face of any public health threat, Dr. Hellerstedt says.

“They’ll never change their behavior until they have a sufficient health literacy so that the facts they read and the things they hear about fit into a paradigm that is internalized, that they trust,” he said.

Advocating is educating

Health literacy is not a well-funded topic, so there’s little recent data showing the impact it has on health outcomes, according to Teresa Wagner, DrPH, clinical executive for health literacy at SaferCare Texas, part of the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth. In January, she formed the nonprofit Health Literacy Texas to provide more research and call attention to the issue (tma.tips/HealthLiteracyTexas).

But older data can outline the scope of the problem, she says. In 2007, the American Medical Association estimated that 90 million Americans lacked sufficient health literacy to undertake and execute needed medical treatments and preventive health care (tma.tips/AMAHealthLiteracy).

That same year, the economic impact of problems tied to health literacy cost the U.S. up to $238 billion annually, according to a George Washington University study (tma.tips/GWUHealthLiteracy).

Physicians have an outsized voice on health matters, and their advocacy can help shape policies statewide, Dr. Sanchez says. That advocacy should focus in part on improving health education in Texas high schools, he says.

In 2009, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) removed a long-standing requirement that all Texas high schools require at least one semester of health education in public high schools.

This change has led to a decline in health education, according to a survey done by the TEA in 2017-2018, the latest year with data available. It found that only 43.58% of Texas high schools required health education in order to graduate.

Universal health education would help students understand at a young age that health information based on science is never static, says G. Sealy Massingill, MD, a Fort Worth obstetrician and gynecologist who has advocated for more extensive health education.

“Science is continually evolving,” he said. “During the pandemic, we had the [director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] come out and say you don’t need to wear a mask, and then two months later he says everybody has to be in a mask. That’s because we learn stuff. And we need to teach our kids how to be thoughtful learners and learn from sources that are accurate and fact-based.”

One of this year’s legislative priorities for the Partnership for a Healthy Texas, which includes TMA, is having Texas require one semester of health education in order to graduate from high school. Physicians also can improve health literacy in Texas by supporting officeholders who back science-based education and voice their support for legislation that promotes health literacy, Dr. Sanchez says.

For instance, two TMA-supported bills currently before the Texas Legislature – Senate Bill 124 and its companion, House Bill 578 – would establish a statewide health literacy advisory committee. The panel would be made up, in part, of physicians and other health care professionals and develop a long-range plan for improving health literacy in Texas.

Efforts to improve health literacy should be backed up with health policy, Dr. Sanchez says. For instance, informing people about good nutrition is helpful, but it does little good without public policy to help those who live in a food desert with little or no access to healthy food.

“Literacy is step one to raise awareness,” he said. “And then you need the conditions that make it possible for somebody to do the thing that they now understand needs to be done.”

Plain language

One of the best ways for physicians to lead on health literacy is by example, says former TMA President Michael Speer, MD, a Houston neonatologist and professor of pediatrics and ethics at Baylor College of Medicine.

Health care professionals relay too much information to patients in language they cannot understand, he says.

“I was always told I had a noncompliant patient who hurts and feels lousy, and I couldn’t figure out why they didn’t do things to make him or herself better,” he said.

Over time, he became aware that even some very simple-sounding instructions leave room for confusion, and he began speaking out publicly on the need for clearer, simpler language when dealing with patients.

For instance, a typical set of prescription instructions might say, “Take tablet by mouth four times a day.” But those instructions mention nothing about whether the pill should be chewed, dissolved, or swallowed, and they give no idea about the intervals at which the pills should be consumed, Dr. Speer says.

“It would be far better to have a label that said, ‘Swallow pill with water before eating morning, noon, night, and bedtime,’” he said.

Using simple, more accurate language is not “dumbing down,” Dr. Speer says. A typical patient reads at a sixth-grade level, so all materials – pamphlets, websites, post-treatment instructions, etc. – should aim for that level and use simple words, simple sentences, lots of pictures, and no medical jargon.

“It doesn’t really matter how bright you are, if you’re not familiar with the language – the terminology used in a particular area, like business or law or medicine or geography or you name it – you’re not going to be able to understand,” he said.

That same approach should be used in spoken communication as well, Dr. Sanchez says. For instance, a physician giving instructions can ask the patient to “teach them back” to make sure the physician did a good job of explaining. If the instructions are not understood the first time, that puts the burden on the physician, not the patient, he says.

“Make sure that your whole team understands [the importance of health literacy] and then engages patients in a way that takes that into consideration,” he said. “That [way] health topics are discussed in a way that people can understand.”