A mountain of work for a molehill of money; an administrative boondoggle; irrelevant to many medical practices.

Physicians’ perceptions of Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) have run along these and other unflattering lines since MIPS first launched in 2017. But a Physicians Foundation-funded study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine sought to better quantify how physician practice leaders perceive MIPS, one of the two participation tracks in Medicare’s Quality Payment Program. (The Texas Medical Association has representation on the Physicians Foundation’s board of directors.)

The main themes that emerged from the April 2021 report (tma.tips/mipsperception) will largely sound familiar: MIPS is time-consuming, creates “substantial” administrative burden, and the incentives available are small relative to the elbow grease.

“It takes a whole office full of people to try to keep your head above water,” Rodney Young, MD, a family physician at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) in Amarillo, told Texas Medicine after taking a look at the study. He is chair of TMA’s Council on Socioeconomics. “That’s the challenge to it. You want to be paid. You need the funds to operate. But the reporting requirements can be so onerous that small practices really have a hard time participating in this game.”

The biggest point of disagreement among participating physicians: whether the program improves patient care.

Ultimately, researchers believe their findings may be helpful for policymakers as they try to improve the program.

“To our knowledge,” the researchers wrote, “this is the first qualitative study of practice leaders’ perceptions of MIPS with random selection of participants across multiple specialties and regions of the country.”

Thirty practices, six themes

The study noted the “many concerns” about the program that physicians, policymakers, and researchers already have raised, as well as the 2018 recommendation from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission to eliminate MIPS altogether.

“Despite these concerns, there is little rigorous data on physician practice leaders’ views of the program to guide policy. Prior studies have examined physicians’ views of alternative payment models more generally, or perceptions of MIPS within a single specialty,” the researchers said.

So they conducted “in-depth, semi-structured” interviews with leaders of 30 physician practices of various sizes and specialties, randomly selected using the membership database of the Medical Group Management Association. The participating practices included large multispecialty practices, defined as those with 50 physicians or more; medium-sized primary care and general surgery practices of 10-25 physicians; and small practices of nine physicians or fewer.

Each interview lasted between 45 minutes and an hour. Nearly half of the 30 practices participated in MIPS through an alternative payment model. The study generated six major themes that researchers identified:

- MIPS is understood to be a continuation of previous value-based care programs and a precursor to future ones.

- Measures are more relevant to primary care than to other specialties.

- Whether MIPS improves patient care is a point that not everyone agrees on.

- The program creates “a substantial administrative burden, exacerbated by annual programmatic changes.”

- Incentives are small relative to the effort require to participate.

- External support for participation can help physicians.

“The stick is painful”

Each year, the incentive payments physicians can earn even for “exceptional” performance in MIPS have left physicians underwhelmed, something many practices participating in the study emphasized.

“We were close to 100% performance and got a 1.6% positive payment adjustment,” one practice leader said. “You spend a whole bunch of time and do a lot of work, and then you get a tiny adjustment. It’s not really worth it.”

But for “a number of” practices, researchers wrote, MIPS participation was driven by avoiding a payment penalty, with some perceiving the potential financial hit as “large and distressing.”

“The carrot isn’t enticing,” one practice leader said, “but the stick is painful.”

The question of MIPS’ relevance generated some equally blunt responses from general surgery practices. One practice leader reported MIPS doesn’t offer many measures for surgeons, adding, “We basically choose by what we score the highest on. We don’t really do tobacco counseling, breast cancer screening, flu vaccines.”

Another physician from a general surgery group added that the group “would never do any of these. They are so far from what we can even make work,” and suggested using fewer, more relevant measures.

However, the study said large, multispecialty practices “also reported challenges identifying measures to report on that seemed relevant to different specialists within their groups,” quoting one physician who said it was difficult to find measures that the entire group could meet.

Cappi Phillips, director of clinical transformation and health care quality at TTUHSC, confirmed that measure relevance is an issue. She told Texas Medicine that the center is currently exempt from MIPS but has reported its metrics in the program in the past.

“We bill and report under one tax ID number, so we also have several specialists within our practices,” Ms. Phillips said. “The specialists, pure nephrologists, may not have a lot of interest into whether your patient has had a mammogram or things like that. Different metrics are very unattainable to different providers.”

Practice leaders in the study took MIPS’ administrative burden to task as well, saying yearly changes exacerbate that problem, such as adding or removing new measures or changing the weighting of MIPS categories. One physician said it “seems like CMS can’t leave things the same ever,” while some interviewees suggested MIPS burdens created a wider-reaching malaise, resulting in burnout and premature retirement.

“The docs are frustrated with the extra clicking and form filling out,” one physician said. “The price that they are having to pay is burnout. It’s just not rewarding.”

The patient care debate

If like some respondents your own answer to the question of whether MIPS helps patient care is an emphatic “no,” the study’s findings may hold a slight surprise.

Just five of the 30 practices expressed “consistently negative views” of the program, according to researchers’ analysis of the interview transcripts. Three expressed consistently positive views, and the vast majority – 22 – were “intermediate or ambivalent.”

Four of the five practices with consistently negative views were in the small-practice category.

“Some participants suggested that MIPS is beneficial in theory, but the complexity of the program renders it ineffectual and burdensome,” the study said. “Participants who reported MIPS improved care cited greater attention to activities that might otherwise have been neglected – annual wellness visits, chronic disease management, services for hearing-impaired patients – while those who had negative views of the program felt such measures were irrelevant to their practice or required burdensome data collection and reporting activities they were already engaged in.”

While one doctor said, “MIPS has absolutely hurt. I see no benefit for patient care,” another said the program’s end result, “which is keeping patients healthy, closing gaps, keeping people out of hospital – that goal is what internal medicine is all about. But the hoops that we have to jump through are sometimes very onerous.”

Another said it “feels like” the program helps patient care, adding, “In the beginning, that was hard to see. But I can now see that it’s come full circle. It’s becoming less of a burden – maybe there are less things to do, or maybe we’ve figured it out.”

But even those with a more positive view of MIPS’ effect on patient care noted the program’s burden. One physician estimated that “$30,000 a year of my salary would probably be attributed to [MIPS] directly,” and another said that the expense of participating was equivalent to a “full-time person with benefits – probably like $50,000 is needed to make this work.”

Easing the challenges

Whether they like it or not, physicians in the study generally agreed that MIPS is a continuation of where value-based care has been, and a harbinger for where it’s going.

In particular, they cited the former Meaningful Use of electronic health records program as one that had motivated changes in their practices. And their “decision to invest additional time and resources into MIPS participation” partially came about because they believe similar value-based programs are coming, both from public and private insurers.

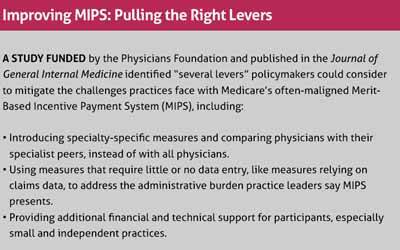

The study offers several suggestions for policymakers to consider to mitigate the challenges. One of those was introducing specialty-specific measures and comparing specialists to their peers, instead of comparing them across all physicians. (See “Improving MIPS: Pulling the Right Levers,” below.)

“We’re trying to move in a direction of knowing what you need to do for a given physician,” Dr. Young said. “But it would help if we didn’t have this many different sets of boxes applying to different people so that it’s not so administratively complicated and it becomes more attainable.

“Right now, you feel like there’s so many of these things that come along that it’s overwhelming, and that creates a feeling of large helplessness, like you can’t succeed in this environment.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(6):40-44

June 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page