The Austin Regional Clinic’s (ARC's) first foray into augmented– or artificial – intelligence (AI) technology started off a challenge but ended well.

In 2018, California technology company Notable approached the Central Texas practice with a plan to reduce the patient documentation burden on ARC physicians, says Manish Naik, MD, ARC’s chief medical information officer and a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Health Information Technology.

Notable set up a system in which ARC physicians used an Apple watch to record their conversations in the exam room, and then AI technology translated that entire conversation into notes.

That was the challenging part, Dr. Naik says.

“It’s just hard to get all the nuances of a patient visit to translate into a note that actually is accurate,” he said.

After this, Notable and ARC came at the problem of reducing administrative work in a different way. First, Notable Health produced a less-ambitious software that lets physicians use a portable device like a smartphone to access voice recognition software and commands that fill out visit documentation templates while they’re with the patient. (See “Custom Fit,” page 26.)

But the real step forward in AI came in two areas tied to patient intake. Notable created software that automatically texts ARC patients a previsit questionnaire based on their patient history. So, patients with a history of high blood pressure or diabetes receive a questionnaire tied to the appropriate condition.

“When the doctor sees that patient, that part of the history is already completed, and it just needs review and editing,” Dr. Naik said.

The AI technology also automatically creates the physician orders that patients typically receive, such as lab orders for a preventive exam, he says. These orders, which must be signed by the physician, can simply be reviewed during the visit and used as needed.

“The orders and previsit questionnaire are [innovative], and I think some doctors have found that very helpful for their efficiency,” he said.

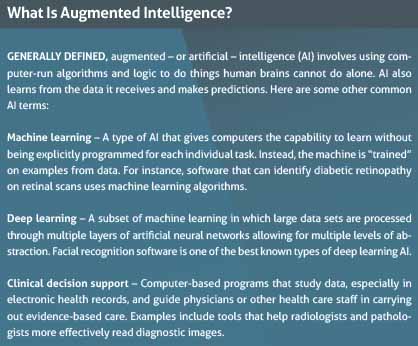

Physicians should learn more about AI because this technology will soon affect their practices directly, says San Antonio radiologist Zeke Silva, MD, who sits on TMA’s Council on Socioeconomics. Dr. Silva is also chair of the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee, which advises Medicare on its physician fee schedule, and he helped form AMA’s Digital Medicine Payment Advisory Group in 2016.

But many don’t know what to make of AI because so few of them have first-hand knowledge, he says.

A 2019 AMA survey of physicians found doctors were familiar with AI use in health administration, clinical applications, precision medicine, business operations, population health, or research and development.

However, actual use of AI in a clinical setting remained in the single-digit percentages for all categories. The exception was for AI for health administration, like the kind ARC uses. Even then, only 11% of physicians said they are using that kind of AI (tma.tips/AMAsurveyAI).

Meanwhile, the demand for physicians to use AI comes from several different directions, Dr. Silva says.

First, physicians themselves are increasingly – and rightly – interested in what AI can do to help with administration and patient care, he says. Second, AI companies are developing increasingly sophisticated products to answer that demand. Third, patients are learning about these devices on their own and will soon expect physicians to apply them to their condition.

“It is probably going to [become more common from] a combination of all three of those,” Dr. Silva says. “But you can see a scenario where these technologies fuse into clinical practice in a way that requires pretty extensive collaboration among all the parties affected.”

Autonomous AI systems – those that can detect, diagnose, and treat without physician review – still remain mostly theoretical, Dr. Silva says. But no matter how efficient or time-saving medical AI technology becomes in the future, physicians cannot allow it to be used without physician input.

“There has to be a human decisionmaking component evaluating the output of the software,” he said. “That’s our responsibility and it’s the responsibility of the [software] developers.”

High-tech triage

AI already is used in clinical settings, and Dr. Silva says his own specialty of radiology is the biggest AI adopter so far. That’s largely because visually driven specialties like his – as well as dermatology, ophthalmology, and pathology – can use AI to more easily analyze lots of data. (See “The Promise of Artificial Intelligence,” October 2019 Texas Medicine, pages 32-35, www.texmed.org/PromisingAI.)

For instance, a radiologist can look at a chest x-ray to see if there is a collapsed lung. At the same time, that physician might also have an AI program running in the background calculating the probability that a collapsed lung is there based on the data that the program has been “trained” to analyze.

“Now I’ve got to look at the x-ray, use my typical process of interpreting an x-ray based on my experience,” Dr. Silva said. “But I also need to process this additional decisionmaking data to decide if that is really a [collapsed lung]. The software is affecting my decisionmaking. … It’s triaging my study to let me know that there might be a greater possibility for a [collapsed lung].”

AI’s ability to provide more information can be both a benefit and a problem, says Austin dermatologist Adewole Adamson, MD, an assistant professor of internal medicine at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. He works with faculty at UT Austin to develop AI software that can help physicians better identify moles that may present a risk of melanoma.

AI is a benefit because it can help screen or triage based on patient information, he says.

On the other hand, in dermatology, AI designed to diagnose specific conditions remains untested, in part because AI algorithms can generate false positives or negatives.

The software Dr. Adamson is working on may take years to develop, he says. But even as AI programs grow more accurate in making a diagnosis, they can in some cases create more – not less – work for physicians because they create more data for the physician to consider.

“There’s this whole other decision point we have to make, versus when it was just you without the technology and just using your own experience,” he said. “It’s another level of decisionmaking. And that extra layer of decisionmaking, is it helpful or harmful for outcomes? We don’t know.”

To help prevent false positives and false negatives, AMA policy calls for data in an AI program to be “locked,” Dr. Silva explains. That means the program has been trained to learn from the data before being put into a clinical setting, but stops learning – becomes locked – once it begins assisting a physician with patients. Locking a program prevents the program from incorporating outlier information that can skew the data set, he says. However, the program still can be updated periodically in a controlled way that continues to enhance it.

Physicians also have to watch for bias in the AI software’s training data, Dr. Adamson says. That was highlighted by a 2019 study published in Science that showed how an AI program discriminated indirectly against Black patients (tma.tips/AIbiasstudy).

The algorithm assigned the same level of risk to Black and white patients, even though the Black patients were sicker, the study says. The authors estimated that this racial bias reduced the number of Black patients identified for extra care by more than half. The bias occurred because the algorithm used health costs as a proxy for health needs. Since less money gets spent on Black patients who have the same level of need, and the algorithm falsely concluded that Black patients were healthier than equally sick White patients.

“Even when you don’t include race as a variable in designing AI algorithms, you can still produce a biased outcome,” Dr. Adamson said.

A tool, not a replacement

The problem with biased data highlights the fact that only physicians can adequately supervise and monitor the recommendations an AI system produces, which should rule out the use of autonomous AI systems in the future, Dr. Adamson says.

Nor, in his experience, are patients comfortable with the idea of AI that works independently from physicians.

“Patients want a diagnosis to be rendered, but patients also want compassion, which AI doesn’t have,” he said. “Patients also want a dialogue with their physician to decide what’s in their best interest for treatment or a type of surgery or something like that. These are human types of choices that have to be made.”

The pace of AI technology is building. The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates medical devices, is approving a growing number of AI systems, Dr. Silva says. (See “Policy and Regulation on Augmented Intelligence,” page 38.)

“And believe me these are remarkable products that can truly benefit patients,” he said.

Texas’ technology companies are among those producing innovative AI. Austin’s ClosedLoop.ai recently won the Artificial Intelligence Health Outcomes Challenge, a competition of the country’s biggest AI producers created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

AAFP members helped judge the entries, and 40% of the overall score was based on how well each AI system interacted with physicians, the organization says in a press release.

The contest for the $1.6 million prize took part in two stages.

The first required companies to use data to predict which patients might face unplanned admissions, serious fall-related injuries, and hospital-acquired infections, says Carol McCall, the company’s chief health analytics officer. The second stage required companies to accurately predict which patients were most likely to die within 12 months. The company also had to show how it used the data to arrive at those predictions.

AI can learn from the mountain of data supplied and – when it’s done right – can cut through the clutter to find the data that is most needed by health care professionals, Ms. McCall says.

“It’s not trying to hunt for a needle in a haystack anymore,” she said. “There are too many haystacks. What I need is a magnet, and AI is this magnet that can pull out all these needles.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(7):36-39

July 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page