For Pedro Calles, DO, one year has made a huge difference in his medical education.

Starting in March 2020, while attending the University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine in San Antonio, he and other students were abruptly pulled from any patient interaction. By late summer they could see patients again – but with restrictions, such as not seeing any patients with COVID-19 symptoms.

Coming as it did during his third and fourth year of training – the time when medical students typically spend the most time seeing patients – the restrictions were frustrating.

“When I was a medical student, I just wanted to help – I just wanted to feel useful,” Dr. Calles said. “And during the pandemic, I felt like a lot of us lost control of education and lost control of [our] ability to be helpful to those physicians.”

Now as a family medicine resident at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) in Amarillo, he has much more freedom.

“I’m seeing what I feel like is a wide variety of patients,” Dr. Calles said. “Do [recent medical students] feel like we missed out on a lot of things? Yeah. But it’s understandable why [medical school officials] did it and how it was handled. And the main reason was to protect us and protect patients and keep everyone safe.”

Dr. Calles’ experience was hardly unique for physician trainees during the pandemic. Everyone in medical education got thrown into an improvised experiment in how to safely train new physicians during a deadly disease outbreak, says Evelyn Sbar, MD, associate professor and vice chair of family medicine at TTUHSC in Amarillo.

In March 2020 – when the pandemic took off in the U.S. – the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) issued guidance that medical students should not be involved in direct patient care activities unless there was a critical health care workforce need in a particular area.

For the first time, a whole cohort of medical students was banned from seeing certain types of patients – especially those with COVID-19 symptoms – until day one of their residency, Dr. Sbar says.

“A lot of what [physicians learn in medical school] – the patient examination skills, the critical thinking – a lot of that was lost, and it remains to be seen how medical students will react in residencies across the county,” she said.

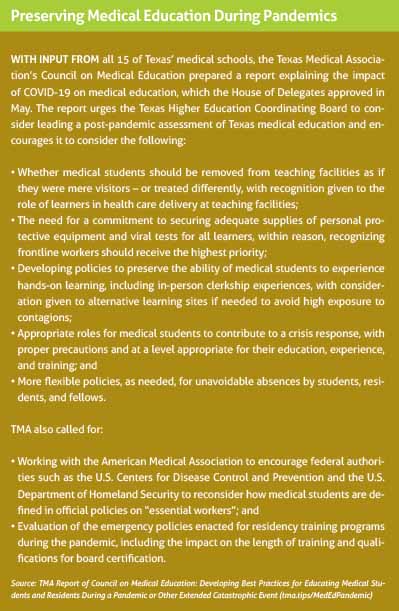

That’s just one example of how medical education was transformed by COVID-19, according to a detailed report by the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education. Adopted by the House of Delegates in May, the analysis provides an overview of the impact of COVID-19 on medical education and offers recommendations for being better prepared for future catastrophic events of this nature. (See “Preserving Medical Education During Pandemics,” page 17.)

The report calls on everyone involved in medical education to “evaluate the policies in place for teaching and training during a pandemic or other extended catastrophic events.” Many of those policies did not even envision the problems that might crop up in a public health emergency such as COVID-19 – they did not anticipate a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), for instance.

Existing emergency policies “were primarily developed with a short-term and localized catastrophic event in mind, such as a hurricane,” the study states. “The policies were not designed to respond to an international pandemic of an extended and uncertain duration.”

TMA adopted the report at a time when it appeared the COVID-19 pandemic was under control thanks to the widespread availability of effective vaccines. Since then, Texas’ vaccination rates have remained stubbornly low, and the fast-spreading delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated population, causing yet another surge in COVID-19. (See “An Overworked Force,” page 30.)

Given that, Texas medical educators, students, and residents have had to postpone the retrospective evaluation and instead figure out how to adapt their training policies yet again to brace for another wave of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths, says Woodson “Scott” Jones, MD, vice dean of graduate medical education who oversees and administers residencies at the UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

“Even as we think of a way forward, we need to be careful not to think that the last solution will work for the next problem,” he said. “Every single surge has a different feel. This surge has different challenges than the first two. On one hand, people are more comfortable combating COVID-19, less worried about personal safety. On the other hand, people are more tired and conflicted by their own attitudes at times, given that a lack of vaccinations is the primary contributor to COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

Class disruption

As Dr. Calles’ experience shows, the pandemic-related disruptions medical students faced have differed sharply from the ones faced by residents.

Medical students faced several unprecedented changes, the report states, including:

• Using virtual medicine in lieu of in-person clinical clerkships;

• In-person preclinical courses that were converted to online formats; and

• The use of electives by medical schools to enable students to earn academic credit for learning about current conditions.

The problems facing medical school students and faculty have changed over the course of the pandemic. Early on, students had to switch to virtual medicine instead of in-person clerkships in large part because there was not enough PPE to go around, Dr. Sbar says.

As the TMA report points out, that presented problems because while some clinical training is conducive to virtual formats – such as dermatology – other clerkships – such as surgery – are not a good fit at all. LCME, the accrediting body for allopathic medical schools, made it clear that medical schools’ curriculum cannot be 100% virtual; some education and training must be provided in person.

Today, the latter is possible in many cases because there’s plenty of PPE as well as vaccines to protect students, faculty, and patients, Dr. Sbar says. But while some vaccines, like the one for hepatitis B, are required for medical students, the one for COVID-19 is not. As a result, some medical students still remain unvaccinated against COVID-19.

“It does make many of us who are chaperoning them and teaching them and precepting a little bit more cautious [in exposing them to patients] because we don’t know [if they’re vaccinated] and can’t ask” due to privacy restrictions, she said.

As the pandemic eased earlier this year, Texas medical schools, like other institutions of higher education, began the 2021-22 academic year with in-person classes, rather than the online classes they relied on earlier in the crisis.

But if schools must switch back to mainly online classes again, they know they can do it now, says Nadia Ismail, MD, associate dean of curriculum at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“There was a big portion of the curriculum in most medical schools where people found out, hey, although there was a learning curve in regard to technology, you can be successful,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, governing organizations for medical licensing exams – the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination and Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination – postponed in-person portions of the tests for safety reasons, the TMA report says. This caused delays throughout the physician educational pipeline – and tremendous stress for students – because those graduating could not easily take the exams needed for residency selection.

In January 2021, the clinical skills portion of the two national testing series were canceled completely in response to criticism that they were too expensive for students and – with a more than 90% pass rate – did little to identify problems. (See “Skipping a Step,” November 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 36-40, www.texmed.org/SkippingaStep.)

Residencies interrupted

Since residents are employees, not just trainees, in many cases they were pressed into service to treat COVID-19 patients, regardless of their chosen specialty.

“Great demands [were] being placed on them in response to various surges in hospitalizations and spikes in demand for emergency and critical care services,” the TMA report notes.

Resident training was disrupted in other ways. For example:

• Clinical activities moved to telemedicine formats when clinics shut down.

• Low patient volumes at times presented challenges to meeting clinical training requirements for some specialties, e.g., primary care, ophthalmology, and surgical specialties.

• Some hospitals temporarily limited operating room activities to essential residents to conserve PPE.

• Some residents were transitioned to elective research projects.

• Residents in global health training programs were brought back to Texas.

• If deemed high risk for contracting COVID-19, residents were reassigned to positions that presented less risk of contracting the illness.

• Residents also were reassigned from community-based preceptorships to other clinical settings.

These and other changes reverberated throughout resident education, Dr. Sbar says. For instance, the high number of COVID-19 cases gave residents plenty of experience in hospital settings. But when COVID-19 cases were widespread, patients tended to cancel outpatient appointments or use telemedicine.

“This group of residents who graduated out of residency last year, they were very comfortable in a hospital, but they didn’t feel like they got the experience they would normally get in an outpatient clinic,” Dr. Sbar said.

Residency programs are highly reluctant to extend residencies because that requires coming up with more funding, she says.

That meant canceled or delayed medical care created an ever-shifting puzzle for residents and their supervisors, since all residents are required to take part in specialty-specific rotations and meet procedure minimums, Dr. Jones says.

“The puzzle gets more complex as programs have to juggle training experiences for the trainees to fill the gaps for the experiences lost while they were either deployed to COVID care or because the needed procedures or rotations were not available for them to get the critical training they need,” he said.

In some cases, this means supervisors must “rob Peter to pay Paul,” as Dr. Jones described it, because they are taking cases away from junior residents and giving them to senior residents who are closer to graduation.

“Our top priority is to graduate qualified doctors,” Dr. Jones said.

However, this ad-hoc system was predicated on the idea that the COVID-19 pandemic would be brought under control this year and that medical training would return to normal, he says. The latest surge due to the delta variant has upset those plans.

“We were betting in this last year that, no worries – we’ll catch up,” Dr. Jones said. “But we’re doing the same thing now. We’re looking at our seniors and saying, you’re the priority, and the juniors are going to get shorted. ... I don’t know how long this is sustainable.”

“Semper Gumby”

The pandemic also disrupted the all-important transition from medical student to resident, the TMA report says.

For instance, the Coalition for Physician Accountability recommended halting rotations away from home institutions for fourth-year medical students in the 2020-21 academic year, hampering the ability of those students to make in-person assessments of their potential future residency training programs and facilities.

The coalition now recommends those “away” rotations for the current academic year, but a bigger problem looms over the process of resident selection, Dr. Sbar says. Before the pandemic, residents traditionally visited the handful of residency programs they were interested in to get an up-close look at the facilities and the people they would work with.

Instead, most interviews boiled down to “couple of phone calls and a FaceTime or a Zoom interview,” she said.

“Our [residency matching process] was much different this year than it was in the past in that we did not match all of our spots [during the original match period],” she said. “That’s just not something that’s happened to us before in many, many, many years. It was partly because you didn’t have people coming to experience our program – the collegiality, the aesthetic part of it, the coming to sit down and have lunch with us.”

Before the pandemic it was impractical for medical students to apply to numerous residency programs, Dr. Sbar says. But technology now allows them to apply to as many as possible.

She’s concerned that may undermine the goal of keeping Texas medical students in state for residencies. Medical students who do their residency training in Texas have an 80% likelihood of staying and practicing medicine in the state, according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Applying for numerous residency programs “is likely to pull residents out of Texas,” she said.

The pandemic has forced everyone in medical education to adapt to new ways to learn, teach, and care for patients, Dr. Ismail says.

“For many schools, the way in which they delivered curriculum was the way in which it was always done,” she said. “The pandemic caused us to rethink how we did things. Although it was disruptive, [with the anxiety] came innovative ways of teaching our learners and delivering patient care.”

Dr. Jones says that trend toward greater adaptability is encapsulated by the military term “Semper Gumby,” which combines the Latin word “semper,” which means “always,” and the name of a famously bendable animation character to create another way of saying “always flexible.”

There are some positive developments caused by the pandemic, he says. “And for me, it’s the professionalism that really comes from a sense of mission and contribution during a crisis. All our trainees and faculty and others can say, ‘I stepped up. I moved out of my comfort zone and did the right thing for patients when they needed us.’”

Tex Med. 2021;117(10):14-21

October 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page