If you want to know why physicians’ psyches are buckling under perhaps the most harrowing emotional challenges they’ve faced in their careers – even more so than earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic – the recent experience of Hilary Fairbrother, MD, may illustrate

why.

Earlier this year, during the first months of vaccine availability, the Houston emergency physician witnessed three patients in one shift – all in their 20s – die of COVID-19. Then she had to call and notify the patients’ families, who hadn’t been allowed

in the emergency department. Then she went home, and her week didn’t get any better.

Dr. Fairbrother ran into someone in her neighborhood who was walking her dog – a neighbor she often talks to and has a great relationship with.

“She said, ‘You know, I’m not going to get this vaccine.’ And I didn’t even say anything,” Dr. Fairbrother recalled. “I just looked at her, and I think [she saw] my look of horror – because she’s elderly, she’s high-risk, she’s got diabetes, she’s overweight.

She’s a retired nurse.

“I was like, holy cow. I just held three people’s hands when they just died of this disease, and they were young and healthy before they came into the hospital. And now this person with this privilege to get the vaccine, who’s not sick, is literally saying

they’re just not going to do it, because they’re just not really sure that they need it.”

Pushback from patients on medical advice and course of treatment is nothing new. But physicians say the degree of it – a lack of trust in science, medicine, and expertise – has never been as pronounced as it is now, in the era of the highly contagious

delta variant, widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines, and millions of people who simply refuse to avail themselves of them. And it’s piling onto the already-existing assaults on physician mental well-being – now increasingly framed as physician

“moral injury.”

“I kind of collected myself,” Dr. Fairbrother continued, “and I just looked at her, and I said, ‘I really care about you, and I just lost three patients today, who are younger and healthier than you, to this thing. I really wish you’d consider and get

the vaccine – because I really don’t want you to be my patient.’

“She actually did end up getting vaccinated. But it wasn’t me. Her husband made her do it.”

Earlier in the pandemic, physicians found their poise tested by the sheer volume of coronavirus patients; fears of contracting it and bringing it home to family; limits on precious hospital and practice resources; and financial stressors brought on by

government shutdowns on certain care and patients unable or unwilling to come in for checkups.

At this writing, many facets of those factors had reared their head again. But in Texas’ third wave of COVID-19, not only have many patients expressed relentless vaccine skepticism and opposition, but also some are self-medicating against the virus with

unproven treatments – such as veterinary drug formulations intended to deworm horses and cows.

Put together with all the pre-COVID-19 factors that fostered widespread physician burnout – such as regulatory and administrative burdens – doctors face a maelstrom of stress. Data collection related to physician stress continues with the pandemic, but

the most recent available data offer both discouraging numbers and possible avenues of improvement.

“Compassion fatigue”

Vaccine skepticism, and increasing misinformation and junk medicine, naturally prompt certain reactions from the physicians who treat patients subscribing to these beliefs, even if doctors keep their frustrations to themselves.

Edinburg pediatrician Cristel Escalona, MD, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Physician Health and Wellness, says the biggest impact she’s seen on her fellow physicians is that they’re suffering from “compassion fatigue.” That is,

they’re struggling to have sympathy for COVID-19 patients who wouldn’t get the vaccine.

The Rio Grande Valley recently earned national coverage for its high COVID-19 vaccination rates: At this writing, Hidalgo County, where Dr. Escalona works, had 75% of its 12-and-over population fully vaccinated, according to state data. Yet Dr. Escalona says

the local children’s hospitals still are “barely keeping up” with illness rates.

“I don’t want to think of what patient care would look like had we not had fair vaccine uptake,” she said.

But her colleagues both locally and around the state are dealing with that compassion fatigue as their hospital systems become overwhelmed.

“You have patients coming in that didn’t have to become so profoundly ill, because this was preventable, and are inundating hospitals to where taking care of everyday things like bronchiolitis becomes a challenge,” Dr. Escalona added.

That frustration is especially acute for older physicians, says Athens family physician Douglas Curran, MD. He’s in Henderson County, where the rate of fully vaccinated residents at this writing was 38%.

“When I was in the first grade, I remember lining up and taking the polio vaccine,” Dr. Curran said. “There was no debate. There was no discussion. You lined up, and we all got the polio vaccine. And Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine, was a

hero. … All that made [for] a different look than what we have now.

“And for those of us who saw that as children, you kind of scratch your head and go, ‘You mean you won’t take this [COVID-19 vaccine] when it means you won’t get [the disease]?’ It makes no sense at all.”

Physicians interviewed by Texas Medicine also found themselves discouraged by a spreading, unscientific belief that the antiparasitic drug ivermectin could treat COVID-19. Ivermectin is approved to treat certain human conditions such as river blindness,

and it’s also available over the counter as a veterinary livestock dewormer. After a summer spike in prescriptions for ivermectin, and reports of severe illness associated with its attempted use as a COVID-19 treatment, the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention issued a health alert in August stating there was “insufficient data” to recommend ivermectin for that purpose.

“We don’t have tools for talking to people who just don’t believe in virology, who think taking a parasite medicine is somehow going to stop a virus. I don’t even know where to begin,” Dr. Fairbrother said. “I’m not used to doing more than explaining

science in layman’s terms as to why this doesn’t work: We have science that shows it clearly doesn’t work, and by the way, it’s dangerous. That’s what I’m trying to do; after that, I don’t know how else to convince people.”

Added Dr. Escalona, “I don’t want to look at social media anymore because it’s adverse to my mental health.”

Physicians like her and Rio Grande City family physician Javier “Jake” Margo, MD, know those platforms are where misinformation salvos are often fired.

“As someone who dedicated the better part of their lives training to be able to answer those types of questions, to have that just simply be dismissed because Facebook or the internet or a friend of a friend of a friend said differently, and to be scoffed

at … I’ve never really seen this degree of skepticism and hostility with trying to provide the best care possible,” Dr. Margo said.

Extreme exhaustion

Extreme exhaustion

Dr. Fairbrother is still engaged and content with being in medicine, saying she was “raised by extraordinary models in how to behave” in an unprecedented time. But her colleagues, she says, are almost universally drained.

“I wish I was being hyperbolic, but we run on our shifts these days because there are so many sick people. They are scattered throughout the emergency department, and our nursing staff in this current surge is so limited,” she said. “We’re literally running,

and my team, the nurses, the respiratory therapists, the social workers – everyone leaves shifts and they are exhausted.

“And then, God save them if they turn on the news. Especially if they turn on the news where a pundit is saying it’s all a hoax, or it’s a conspiracy theory, or the vaccine is worse than the disease.”

Being spread thin is a particular concern at rural hospitals like Dr. Curran’s, where over the Fourth of July weekend there were hardly any COVID-19 cases. Everything came “unglued” right after that as the delta variant overtook the nation.

“We had 64 people in our 115-bed hospital with COVID, and 24 of them on ventilators,” Dr. Curran said in mid-September. “I’ve never seen that before in my life. The most I can ever remember, under quasi-normal circumstances before COVID – we might have

four or five ventilators running in our hospital. But to have 24? Unheard of. And back then [early in the pandemic], we couldn’t have found 24 ventilators.”

Dr. Margo adds that with COVID-19 exposing the inequities that exist in today’s health system, he has concerns about the future of the physician pipeline – most specifically, being able to recruit physicians to go into rural medicine in general, or rural

family medicine specifically: All the obstacles to becoming a primary care physician, and the reasons to not become one, are mounting.

“You run into this never-ending spiral where, at the end of the day, you have more patients than we have physicians. You have real disinterest, or people are being swayed or persuaded from going into primary care, and at the end of all of it, the pay

is not there.”

Feeling valued

Previously released data, such as The Physicians Foundation’s pandemic-focused edition of its Survey of America’s Physicians, already illustrated COVID-19’s profound attack on the emotional state of the profession. (See “No Escape,” February 2021 Texas

Medicine, pages 16-21, www.texmed.org/NoEscape.)

But some of the most recent data on health care professionals’ psychological difficulties with COVID-19 also contain illuminating information on what can help, says an American Medical Association researcher who helped collect it.

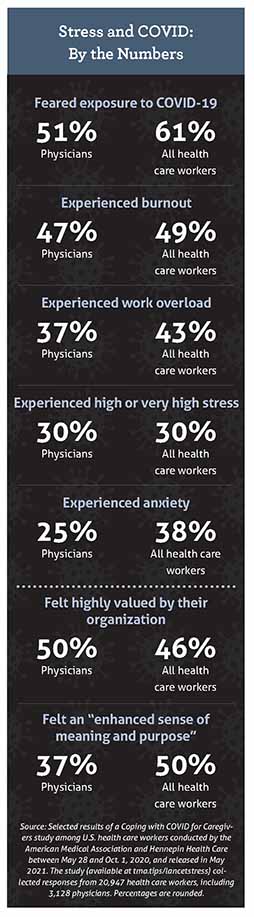

In May 2021, researchers from AMA and Hennepin Healthcare released findings from a Coping with COVID for Caregivers survey of nearly 21,000 U.S. health care workers, with responses collected between May 28 and Oct. 1, 2020. More than 3,000 physicians

participated. Among the results: Thirty percent of physicians experienced high stress; more than half feared COVID-19 exposure; and nearly half experienced burnout. (See “Stress and COVID: By the Numbers,” page 19.)

However, those numbers and the others related to health care workers’ psychological distress weren’t the most important takeaway in the study, says Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and one of the researchers. The

most important finding to her: For health care workers who feel valued by their organizations, the odds of burnout were 40% lower.

Researchers didn’t define what it means to feel valued. But in Dr. Sinsky’s own view, “We do that best by actions that make a difference in physicians’ lives, as opposed to simply by expressions of gratitude. We can feel valued by our organization if

the organization provides sufficient training – if, as a physician, we’re being redeployed from one unit, for example a medical ward, to an [intensive care unit]. Or if you’re being redeployed from an ambulatory clinic in primary care to a respiratory

clinic geared toward COVID.

“Other ways institutions can ensure their physicians and other workers feel valued: providing housing support, mental health support, healthy food and water, and ensuring that staff is able to take breaks even during surges.”

Still other ways, she says, include organizations hosting listening sessions for physicians to share their needs with leaders, and having enough personal protective equipment.

“Having a celebratory ice cream bar is a fine thing to do,” Dr. Sinsky added, “but it’s not the most substantive way that an organization can convey to their physicians and others that they are valued.”

Ultimately, the locus of the problem lies with the environment physicians are in, not the individual, Dr. Sinsky said.

“The bottom line is that physicians do not have a resiliency deficit,” she said, citing other research to that effect. “In practice, physicians have significantly higher levels of resilience than the general population. And even so, burnout is high.”

Despite medicine’s current state of mind, Dr. Curran is “absolutely not” worried about the future of physician practice.

“I am very comfortable that we still have a lot of people left in this country that are going to be available to the profession that are committed to the well-being of our people. And I just don’t see that going away,” he said. “They have the skill, they

have the capability, and they certainly have the opportunity for learning that is going to change us and make us all better.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(11):16-21

November 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page