A decade ago, the Texas Legislature made a funding decision that devastated low-income women’s access to health care and the physicians and community clinics that care for them.

In crafting the final budget for 2012-13, the 2011 legislature cut funding for family planning programs by about two-thirds, chopping it from the previous $111.5 million to just under $38 million. Lawmakers targeted the cuts at Planned Parenthood, but they impacted all physicians and clinics that provided preventive health care to low-income women.

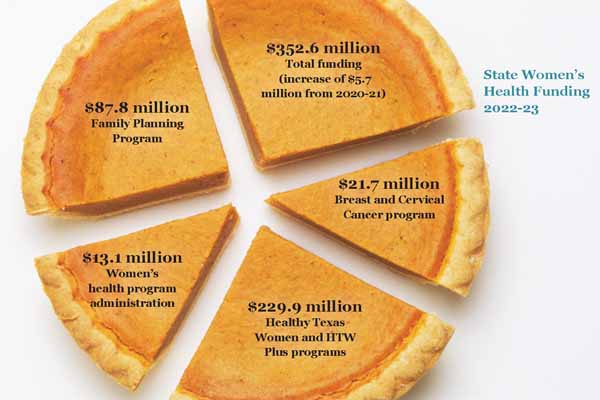

After 10 years, with the help of TMA advocacy and the formation of the Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition (TWHC), funding for family planning and overall women’s health is in significantly better shape. That rebound began during the next session in 2013, and during this year’s regular session, lawmakers kept women’s health services off the chopping block, giving those services a modest increase for 2022-23 to more than $350 million overall. The state allocated to its current Family Planning Program more than twice as much as it distributed for family planning during those dire days of 2011. (See above.)

While more money always helps, physicians and other women’s health advocates say there’s still room for growth in the state’s programs not only financially but also operationally.

“We want to promote women’s health in Texas, and that means making sure that women have access to good health care,” said Austin oncologist Debra Patt, MD, chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Legislation during the 2021 general session of the legislature. “Cuts to programs that fund women’s health care are a challenge, because we have a really critical group of individuals that needs access to low-cost services to promote their health and wellness.”

Cutbacks, closed clinics

After the legislature made those dramatic 2011 reductions, the state had to figure out how to spread out 66% fewer family-planning dollars, notes Evelyn Delgado, who at the time was overseeing women’s health programs at the Texas Department of State Health Services. Today, she’s chair of TWHC, a coalition of organizations that collaborate to promote access to preventive health care for Texas women. TMA serves on the coalition’s steering committee and spearheaded its formation following the 2011 cuts along with a broad range of women’s health advocates.

Ms. Delgado said physicians, clinics, and others offering women’s health services “need at least a base amount to be able to operate as a business in that community.” Some had to see fewer patients. For others, she said, “their organizations had to reduce hours, eliminate certain days that they would provide services, and worst-case scenarios, they had to close clinics, which left many communities without access in their own town.”

Physicians and advocates were concerned not only about unintended pregnancies as a result of the family planning cuts but also about less-healthy pregnancies, recalls New Braunfels family physician Emily Briggs, MD.

“The benefit of being able to spread your pregnancies as a woman is to be able to, for instance, lose weight from the previous pregnancy, or get into a healthier place either emotionally and mentally, or physically. And when you don’t have that access to that care, then you don’t have the ability to space that pregnancy appropriately,” she said. “Therefore, you don’t have the opportunity to have a healthier advanced pregnancy, necessarily.”

More than 80 clinics statewide ended up closing as a result of the cuts, Ms. Delgado said. “Women wanted to be able to access well-woman visits, they wanted to access contraception, screening services, and they just were not able to.”

And clinics that survived the financial purge had to be more selective about the types of contraception they offered. “They had to cut back on some of the more expensive forms of contraception, which sometimes is the exact contraceptive method that a woman needs,” such as intrauterine devices and sterilizations, Ms. Delgado added.

Medicaid pays for roughly half of the births in Texas each year. Typically, around 30% of Texas pregnancies are unintended each year, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention annual data in its Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring survey.

“So many pregnancies are unintended, and those pregnancies might not have happened if women had access to contraception, and those pregnancies end up being a lot of what Medicaid pays for,” Ms. Delgado said. “It costs the state and the federal governments money; the state has to provide a match” on federal dollars. “So, it just didn’t seem to make sense to have such drastic reductions when we knew there would be later additional costs as a result.”

“A much better place”

Since then, the legislature has heeded much of TMA’s and TWHC’s biennial calls to reinvest in the health of Texas women. This year, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, medicine’s advocates were happy to see that lawmakers didn’t cut any funding from women’s health programs, instead signing off on a modest increase of $5.7 million over the previous budget.

The $352.6 million investment the state made for 2022-23 included nearly $88 million for the Family Planning Program – a far cry from the less than $40 million it allocated 10 years ago. (See “State Women’s Health Funding 2022-23,” above.)

“I’m glad [the state] recognized that these programs are so important, because we still have this high level of uninsured, high level of poverty, and access to women’s health care [for] preventive family planning is difficult,” TMA lobbyist Michelle Romero said. “We’ve made a large investment. But it has been hard-fought.”

Along the way, Texas made some accompanying administrative improvements. In 2016 for example, the state combined two existing programs into Healthy Texas Women (HTW), which provides preventive health services, screenings, and immunizations for low-income women, including basic primary care and access to contraceptives. The same year, the state launched an expanded version of the Family Planning Program.

Both HTW and Family Planning have since expanded age eligibility. And in September 2020, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which oversees both those programs, launched HTW Plus, which offers enhanced but still-limited postpartum services for up to 12 months after pregnancy, including treatment for postpartum depression, other mental health conditions, cardiovascular and coronary conditions, and substance use disorders.

However, the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act enhanced federal Medicaid funding for states in exchange for maintaining Medicaid eligibility for anyone enrolled on or after March 18, 2020, through the end of the federal public health emergency.

Shortly before press time, the Biden administration extended the public health emergency through Jan. 16, 2022. That means postpartum women who enrolled in Medicaid from March 18, 2020, onward, and who would otherwise be eligible for HTW and HTW Plus, are allowed to stay in Medicaid.

“We are certainly in a much better place now. I’m excited to see what HTW Plus will look like, boots on the ground,” Dr. Briggs said. “We have this great program that our Texas physicians helped to guide the legislature [to], to some extent. We definitely spoke to a lot of people in trying to get these different aspects of HTW Plus to be part of it. There is input into this new idea, but again, we just don’t know … what that will look like because there hasn’t yet been that opportunity to really use it because of the public health emergency.

“So, it’s that hopeful place of, ‘Maybe our women will be able to have access to not just screening, but also management of these conditions.’ Mental health is such an important aspect not just of a new mom’s life, but of the whole family’s care.”

Shooting for better

It’s in these state programs where advocates say Texas can still make plenty of improvements.

For instance, new mothers who had been in Pregnant Women’s Medicaid were automatically enrolled in HTW once their Medicaid eligibility expired. But once HTW became a program funded by the federal Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) had to operate the program by federal Medicaid rules, which HHSC argues don’t allow for automatic eligibility but instead determine it based on income.

The Texas Women’s Healthcare Coalition continues to advocate for reforms to protect continuity of care as women transition from pregnancy-related Medicaid to HTW.

“The auto-enrollment was the best way,” Ms. Delgado said. Now “only [an estimated] one out of 10 women will automatically get enrolled. [For] the rest … HHSC will have to request additional information from them to confirm that they are still eligible.”

On the plus side, HTW doesn’t run out of funding each year, she says. That’s not the case with the Family Planning Program, which typically exhausts its annual funding by the spring or summer, before the new fiscal year begins.

When that happens, clinics providing services in the program “have to find other funding that they may have in their clinic from other sources to continue to serve those women until they get their new money again in September,” Ms. Delgado said, often reducing appointments in the meantime.

Dr. Patt, the Austin oncologist, believes another opportunity exists in expanding eligibility for the Medicaid portion of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Services (MBCC) program, saying while its low-cost screening and diagnostic services are useful, its eligibility requirements are “a little bit stringent.” She said patients fall through the cracks of the program, and it’s sometimes difficult for them to obtain the needed care.

“We need to continue to invest in women’s health care. We need to improve the eligibility requirements for the MBCC program, continue to increase funding for women in the postpartum settings,” she said, referring to the legislature passing a law this year to extend Medicaid coverage for women postpartum from two months to six months. “I’d love to see that [extended to] a year. Women who’ve recently had children, and their children, are special vulnerable circumstances, and we need to make sure that we protect them. It’s in our overwhelming best interest.” (See “Saving Mother’s Lives,” page 26.)

During this year’s third special session of the legislature, TMA urged lawmakers to expand income eligibility for the MBCC program to the maximum allowed by federal law, up to 250% of the federal poverty level. That push wasn’t successful, but TMA will advocate for it again during the 2023 session.

Tex Med. 2021;117(12):32-34

December 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page