This year’s Match Day will be an even bigger event than it usually is because it’s part of an unprecedented experiment in medical education.

The experiment started during the interview process for the 2021 Match, which coincided with the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before then, virtually all U.S. residency programs used in-person interviews to select residents, and only a handful had tentatively tried interviewing online.

COVID-19 flipped that dynamic: Suddenly almost all residency interviews were done online for the first time to prevent the disease from spreading.

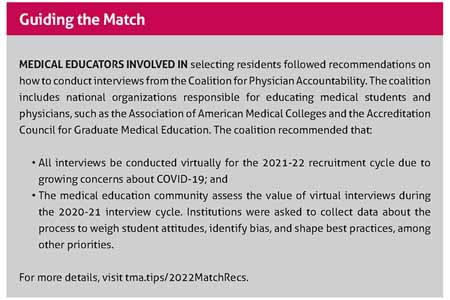

That continued for the 2022 Match. The Coalition of Physician Accountability recommended virtual interviews this academic year as a way to standardize interviews during the pandemic and to further study the impact of the virtual format. (See “Guiding the Match.”)

While many educators have accommodated themselves to the new reality – and even seen the advantages of virtual interviews – the change has not been easy, says Evelyn Sbar, MD, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education and associate professor and vice chair of family medicine at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) in Amarillo.

Many educators still believe in-person interviews are the most effective way for programs to determine who is the best fit to interact with fellow physicians and patients.

“It’s difficult to get a good feel of what that person is like [online],” she said. “The virtual process doesn’t let you determine people’s mannerisms, how they interact with other people in the hall, or what their handshake feels like. Some things that may be very important in the physician-patient interaction are hard to judge virtually.”

In-person interviews also give prospective residents a better idea about the program they intend to join, she says. For instance, residents affiliated with TTUHSC serve a largely rural population, which not all candidates are comfortable with. Also, Amarillo is a long way from other metropolitan areas. Students accustomed to living in big cities might not understand how remote it is unless they visit.

Medical educators will have a better read on virtual interviewing after this month’s Match is over, Dr. Sbar says. But many educators agree that at least some parts of the virtual interviewing process may be here to stay.

Perhaps the biggest reason is that online interviewing has proved equitable for many students, says Jonathan MacClements, MD, a consultant to the Council on Medical Education and associate dean and designated institutional officer of graduate medical education at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School.

For instance, students don’t have to worry about the cost of travel when lining up interviews – a huge consideration for students already deeply in debt because of medical school, he says.

These and other factors have caused a landmark change in thinking for medical educators, Dr. MacClements says. Many are now looking for ways to combine the equity of virtual interviews with the intimacy of in-person interviews, he says.

“Everybody would like to move back to in-person because there’s a lot to be said for the in-person experience,” he said. “But there’s the recognition that the virtual space has created more equity and has also created more efficiencies. I think people would feel more comfortable with a hybrid interview process.

”

”

Madeline Hazle, a fourth-year student focusing on family medicine at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine, did most of her 12 interviews virtually and saw a lot of benefits to that format. The money she saved by staying home was a huge plus, she says.

“I applied to [programs in] other states as well as Texas, and so I would have had to travel,” she said. “And [each interview] also took less time. I think each interview only took about half a day of your time, so it was a lot more flexible,” than the typically full-day interviews of the past.

The relative ease of online interviewing also reduces stress, says Aman Narayan, a fourth-year student at UT Southwestern Medical School in Dallas who hopes to match to an internal medicine program. During the period when he interviewed, he also served in a subinternship for cardiac care.

“It’s a very busy rotation for me,” he said. “You’re expected to serve as an intern … and it’s very difficult to get time off. If I had to juggle interviews where I was actually traveling to places, that would be very difficult because it would be hard to get two or three days off to travel.”

Online interviews present an array of technical and logistical problems as well, but medical schools and students have worked hard to overcome them, says Joshua Hanson, MD, associate dean of student affairs at the Long School of Medicine. For instance, finding an interview location with adequate internet, a good webcam, and the right background can be difficult.

“It’s not necessarily easy to have a professional-looking environment in your apartment when you’re a fourth-year medical student,” he said. “When I think back on my fourth-year apartment, I don’t know where I would have conducted the interview.”

The Long School of Medicine has helped students overcome this by providing interview spaces in the university library, Dr. Hanson says.

Online technology can be glitchy and unreliable, so students must learn how to roll with technical difficulties, says Ruth Levine, MD, associate dean for student affairs and admissions at The University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine in Galveston.

Medical schools also have provided mock online interviews and other media training to help students get used to presenting themselves on camera, she says.

“People who are very good in person may not be as good at [online interviews],” she said. “This is not a skill that’s intuitive.”

Computer fatigue also is a serious problem for students during interviews.

“It can be kind of difficult to sit on Zoom for a whole day or half a day or whatever it might be,” Mr. Narayan said. “It really gave me insight into all the kids in elementary school who had to do virtual school for a year. That part of it is really exhausting.”

Even so, the benefits of online interviewing outweigh the drawbacks, he says. “Overall, it’s been a good experience. I’m happy that things are virtual.”

Ms. Hazle says one of her favorite selection processes was actually a hybrid in which the interview was done online and a follow-up open house for all applicants took place in person.

Given the traditional affection for in-person interviewing and the advantages of online interviewing, some sort of hybrid system seems inevitable, Dr. Hanson says.

“[Online interviewing] is probably not going away,” he said. “I don’t know if it will take the same kind of form in future years, but it will most certainly be present in some way.”

Besides the process, however, schools are monitoring the impact the move to virtual interviews could have on candidate selection.

For instance, Mr. Narayan says it inadvertently blocks some people from ever being considered for some residencies. When residency interviews were done in person, students frequently canceled at least some of their appointments either because those appointments were low priority or because the students could not find the time or money to attend. That allowed others on waiting lists for those programs to move up and do those interviews instead.

But students who book a lot of online interviews have fewer incentives to cancel now, so they don’t, he says. That means people on the waiting lists are effectively eliminated from being considered for those programs.

“At least anecdotally, this has affected me and some of my friends who’ve interviewed,” Mr. Narayan said.

The way schools prioritize interviews, the students first in line for residency interviews usually have the highest test scores and grades, Dr. Sbar says. So those crowded out of interviews are most likely those with slightly lower academic achievement in medical school – students who are still highly desirable as residents.

“Who are we to say that someone who’s got a B average is not going to make a fantastic doctor?” she asked.

In part to address this problem, the TTUHSC program in Amarillo has already increased its number of interview slots per residency position from about eight to 20, says Nolan Farmer, DO, associate residency director and assistant professor of family medicine there. But residency programs can only expand that number so far because they don’t have the staff to do more.

After Match Day each year, there is a second round of matching for the residency programs and medical students who remained unmatched called the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP).

After last year’s Match Day, the residency program at TTUHSC had to use SOAP for the first time in many years to fill a residency position, Dr. Farmer says. Also, a higher number of desirable TTUHSC medical students had to use SOAP to match with a residency.

“A ton of good, qualified students found themselves on the SOAP list, and that’s not something we’ve seen in the past,” he said.

If that happens again this year, it may be a sign that online interviewing can be equitable in removing economic barriers for interviews but inequitable in the actual selection of residents, Dr. Farmer says.

Medical educators also will be watching to see if the number of residents who want to switch programs in the next year or two is higher than normal, adds John Slaton, DO, residency director and associate professor of family medicine at TTUHSC in Amarillo.

“The attrition rate will be something to pay attention to,” he said. “If [residents] were perhaps admitted into a program, and it wasn’t what they thought it was going to be, or they just didn’t like the personnel or the management … that’s going to be a huge part of this if we can tie a higher attrition rate to the virtual interviews.”

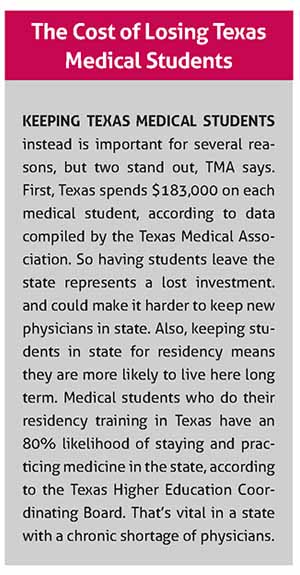

Since there are fewer geographic barriers to interviewing with out-of-state residency programs, some medical educators wonder if online interviewing may cause a greater number of Texas medical school graduates to go elsewhere. (See “The Cost of Losing Texas Medical Students.”)

That concern may not pan out though, Dr. Hanson says. For instance, the data so far from the Long School of Medicine show that students are not leaving the state in large numbers.

“Last year, our proportion of [Long School of Medicine] students who were staying in the state was about the same [as in prepandemic years],” he said. “About half of our students stayed in Texas, and that’s what happened the [previous] year.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(2):40-45

March 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page