For a practice that predominantly sees Medicaid patients, a transition to unfamiliar, value-based payment models can seem like a seriously heavy lift.

But another heavy lift has persisted for more than two decades, and it hasn’t gotten any lighter: securing a worthwhile Medicaid physician payment increase for traditional fee-for-service setups.

Despite the Texas Medical Association pushing for a significant pay bump every year that the Texas Legislature meets, lawmakers have yet to break that streak. As long as it continues, physicians looking to make Medicaid more worthwhile for their bottom line have to find another way.

Value-based systems – and the alternative payment models (APMs) that drive them – have been the path Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and practitioners have been methodically walking in recent years. And Mary Dale Peterson, MD, executive vice president and chief operating officer of Driscoll Children’s Health System and member of TMA’s Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured, doesn’t mince words about why medicine needs to stay on that path. The system maintains Driscoll Health Plan, a Medicaid MCO.

“We all know that Medicaid fee-for-service payments, they won’t sustain a practice. It’s way below cost,” Dr. Peterson said. “We need to get more physicians on board negotiating with the MCOs for payments that will make their practices viable, even if the majority of our patients are Medicaid. Medicaid patients need timely access to care, and physician practices need to be paid their costs. The only current path to accomplish this is in the value-based format that the state is supporting.”

Thus, the work on value-based models that was already full-steam prior to the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

In fact, some of the most recent value-based payment initiatives in Texas Medicaid have been pandemic-driven.

Maria Scranton, MD, chair of the Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured, is a pediatrician at Austin Regional Clinic (ARC). Both COVID and ARC’s value-based contracting prompted the clinic to find a way to finally bring down avoidable emergency department (ED) utilization, she told Texas Medicine. ARC had been wanting to tackle that notorious cost drain, and the pandemic prompted patients to more frequently call ARC first before heading to the ED.

It has always been a challenge to educate patients that the “little things” can wait, she said.

But ARC also discovered that sometimes when patients called, its nationally validated triage protocols “were forcing patients to go to the [ED] that really maybe didn’t” need to, such as a child’s surface head injury that didn’t rise to the level of emergent, she said.

After taking a hard look at such cases, the clinic implemented a system in which a nurse can securely use the electronic health record to text the physician, with the patient’s chart attached. Dr. Scranton can then judge whether to give the patient or family phone advice, have the nurse send the child to the ED, or bring the child in for a visit.

For Driscoll, the crisis in child behavioral health – exacerbated by the pandemic – is the impetus for an in-progress behavioral health integration pilot program. It involves distributing grants to practices for the administrative and startup costs to integrate a mental health professional and best practices in a pediatric primary care setting. The goal: aiming for “whole-person care” that coordinates efforts to improve both physical and mental health.

During the pilot, Driscoll is paying for behavioral and mental health services on a fee-for-service basis. Karl Serrao, MD, Driscoll Health Plan’s chief medical officer and member of TMA’s Medicaid committee, explained that the purpose is to collect information and assist the practices in the integration over an 18-month to two-year period. If the practices have success in the program, Driscoll will create an APM to sustain integrated behavioral health in pediatric primary care.

“We want to limit the number of patients with mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders being referred to psychiatry, which is already overburdened and under-resourced in our community. Because they can be managed in the primary care practice. And by better managing the patient’s mental health, you can address their physical health issues as well,” he said.

Dr. Peterson added that the pandemic has “pushed us to try to make sure, as a system, that we’re providing more care at an earlier level for kids, so they don’t end up in our emergency department in crisis and attempting suicide.”

Also, the rapid expansion of telemedicine in response to COVID was a fortunate turn for many practices in value-based arrangements, says William Brendle Glomb, MD, senior medical director at Superior HealthPlan. He notes that when much of routine care fell by the wayside early in the pandemic, it became difficult for practitioners to hit their value-based payment targets.

But more availability of telemedicine options, and a broader definition of what constitutes telemedicine, helped reverse that early tide, Dr. Glomb told Texas Medicine via email.

“Many providers were able to implement this new care modality effectively and return to some level of patient volume and flow, closing care gaps, and returning to levels of financial success,” he said. “It appears that HHSC may leave the telemedicine benefit available as-is after all pandemic-related restrictions have been lifted, [which would be] a win for many providers who have had the resources and ability to adapt.”

Another one of the silver linings of the pandemic, Dr. Peterson notes, is that it pushed more of Driscoll’s practices into APMs – Medicaid’s only identified route to making value-based care a reality. However, those alternative models are still a mystifying entity to many physicians – if not downright inaccessible.

Those realities drove TMA’s recommendations in a letter to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) earlier this year, when medicine weighed in on HHSC’s next planned version of its value-based care “roadmap.”

Beginning in 2018, HHSC introduced a pair of minimum APM requirement thresholds for MCOs. For 2021 and this year, MCOs must have at least 50% of their total practitioner payments for medical and prescription expenses in APMs, and at least 25% in a risk-based APM.

TMA’s letter reiterated several barriers and challenges for widespread APM adoption previously noted by an HHSC advisory committee on value-based care, including lack of standardized performance measures and too little financial reward for the cost of implementing and maintaining an APM system.

TMA and the other signatories on the letter – among them the Texas Pediatric Society and the Texas Academy of Family Physicians – proposed their own recommendations and supported others from the HHSC advisory committee. One of the advisory committee’s proposals: that the agency establish a menu of standardized APMs that practices can choose from, instead of expecting an under-resourced practice to come up with an alternative model of its own.

Most practices, TMA’s letter noted, “lack the expertise, staffing, or financial resources to design something fresh.” And the majority of Texas physician practices are groups of 10 or fewer, TMA’s letter added.

“Thus, providing a menu of turnkey APMs would encourage greater participation among smaller groups without precluding practices and MCOs from voluntarily collaborating to tailor models to their unique circumstances and/or test new ones,” wrote then-TMA President E. Linda Villarreal, MD, and the presidents of the other organizations. “Texas Medicaid also should work closely with physicians and MCOs to reduce health disparities by promoting APMs that encompass measures to address social determinants of health. While such initiatives already exist, having explicit support and framing from HHSC would help encourage faster adoption.”

Dr. Serrao notes that in value-based arrangements, practices also have another consideration besides refocusing on quality and clinical outcomes: They have to take on some amount of financial risk.

“We can’t throw them into the deep end,” he said, and implementation is a complex learning process that doesn’t bring with it a one-size-fits-all model for any type of shop. (See “The Value-Based Care Continuum,” page 16.)

TMA’s letter also encouraged HHSC to promote APM adoption to sustain a robust primary care system, including encouraging MCOs to give practices financial certainty using prospective payments. Aligning Medicaid MCO performance measures with those of other payers was another point of emphasis.

“The bane of physicians who want to do alternative payment models is trying to align them across Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial payers,” Helen Kent Davis, TMA’s associate vice president of governmental affairs, told Texas Medicine.

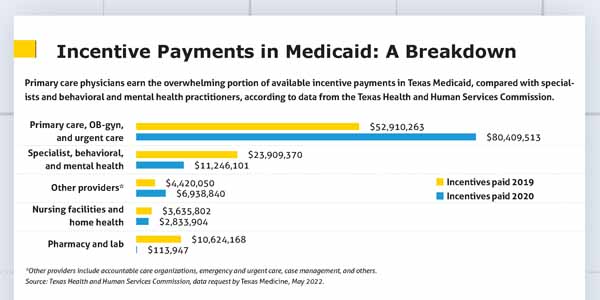

TMA also said Texas Medicaid should work with medicine to develop APMs and incentive-based payment setups for subspecialists, whose alternative payment options are currently sparse. (See “Incentive Payments in Medicaid: A Breakdown,” page 27.)

At its May meeting, the HHSC advisory committee commended TMA’s recommendations and noted it intends to include some of them in a report to the legislature later this year.

Medicine also cited stagnant Medicaid fee-for-service payments as a barrier to APM adoption.

“While APMs often result in higher payments for participating practices, HHSC still bases MCO capitation rates (in part) on the Medicaid physician fee schedule,” TMA’s missive noted. “Over time, it becomes increasingly difficult for APMs to achieve savings to share. Thus, it goes without saying Medicaid physician payments must be increased.”

There’s a classic catch-22 involved there, though: Effective APM development is necessary precisely because the pay increase is so hard to attain, physicians say.

“This is something that I do have some passion for trying to make it work, because I honestly don’t see any other options to help Medicaid move forward at this point,” Dr. Scranton said. “If we’re going to wait for the legislature, and even to some extent HHSC, to do this for us … it’s going to be so super-slow that a lot of people are going to go out of business or get burned out before it’s fixed.”

Bluntly, Dr. Peterson added: “I don’t see the legislature moving towards increasing physician payments in that fee-for-service model. So, we’ve got to find another way of making sure practices are viable through these APMs. And that should be all of our [collective] goal.”

A promising step came during last year’s legislative session, when lawmakers directed HHSC to study whether increasing Medicaid physician payments for services provided to children up to age 3 would reduce ED and hospital costs. HHSC must submit the study results by Nov. 1. If the agency finds such an increase is likely to save money, it must launch a pilot program for the payment increase in March 2023.

Tex Med. 2022;118(6):26-28July 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page