Congenital syphilis is one of those antique health care horrors, like smallpox, that’s right out of a Victorian medical book.

“It’s catastrophic for the baby because it can cause birth defects and significant abnormalities,” said San Antonio obstetrician-gynecologist Patrick Ramsey, MD, chief medical officer for the Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies (TCHMB), which includes the Texas Medical Association. “Everything from stillbirth to abnormalities of the bones and teeth, neurologic issues, and long-term injury to the liver and spleen.”

But unlike smallpox, the “great pox” – as syphilis was once called – has not died out. Syphilis and congenital syphilis declined sharply in the late 20th century because they are easily treatable with penicillin.

But they have made a comeback fueled by a number of factors, including public complacency, increased opioid use, lack of adequate prenatal care for low-income mothers, and nonmedical drivers of health – such as lack of transportation to and from physician appointments, says Houston obstetrician-gynecologist Catherine Eppes, MD, who serves on TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health.

In addition, over the past two years, COVID-19 has discouraged people from obtaining medical care, Dr. Ramsey says.

“I’m sure the COVID-19 pandemic made it more challenging for people to come in for visits and made it more difficult to identify the rash they may have had early on,” he said.

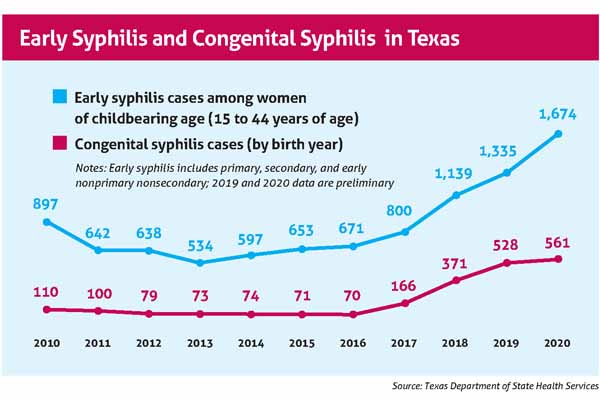

As a result, Texas has the highest number of congenital syphilis cases of any state, with 561, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (See “Early Syphilis and Congenital Syphilis in Texas,” below.)

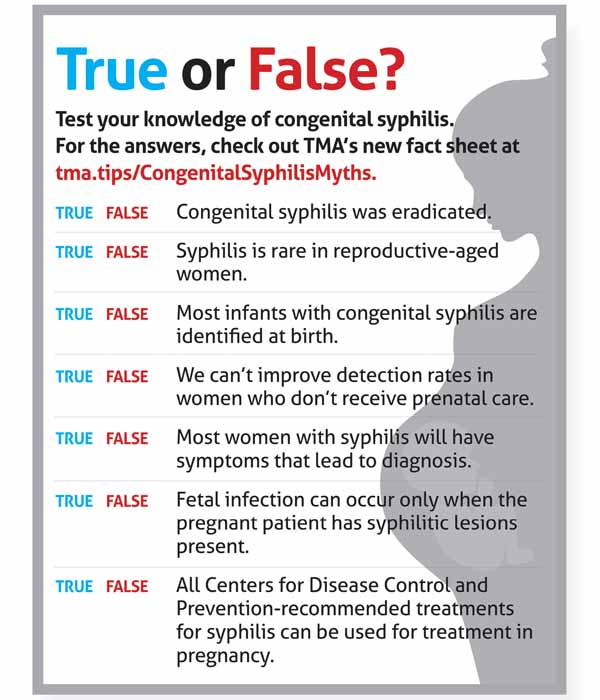

To address that resurgence, TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health; its Committee on Infectious Diseases; and TCHMB worked with the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) to produce a fact sheet and CME designed to help clinicians understand why congenital syphilis is a growing public health concern and how they can address it. (See “True or False?” next page, and “CME from TMA,” page 40.)

Part of the problem is that many people – including physicians – discount the threat syphilis poses to pregnant women, says Jennifer Shuford, MD, chief state epidemiologist with DSHS.

“A lot of people think that syphilis may have been eradicated and that we don’t have congenital syphilis anymore. Unfortunately, that is not true,” she said. “In recent years, we’ve seen increases in both adults and babies.”

Physicians cannot address all the circumstances that have contributed to the rise in both syphilis and congenital syphilis. But epidemiological evidence shows physicians are key to stopping the rise, Dr. Shuford says.

A DSHS investigation into the state’s 2018 cases of congenital syphilis showed that many of the women involved received timely diagnoses of syphilis at least 45 days prior to delivery, Dr. Shuford says in the CME presentation. Unfortunately, only 28% of those women had timely, adequate treatment.

“The reason this is important for physicians is that we know from our case investigations that some of these pregnant women were actually in prenatal care in time to get diagnosed and treated for syphilis, but they just weren’t treated in time to prevent a case of congenital syphilis,” Dr. Shuford said. “So, there are some missed opportunities for treatment of these women among physicians.”

Clinicians in all specialties should be on the lookout for syphilis because the problem affects patients of all backgrounds, Dr. Shuford says.

“We are seeing syphilis in women of reproductive age all across our state,” she said. “It’s not something that can just be identified by obstetricians. It can also be identified in emergency room visits and by primary care physicians. There are lots of opportunities for physicians … to help us decrease congenital syphilis in Texas.”

Syphilis remains an infamously difficult disease to diagnose. It’s been called the “great imitator” because its symptoms come and go, and many of them are so general that their source is hard to pin down.

Syphilis develops in stages, and the symptoms vary from stage to stage; they include painless sores, rashes, hair loss, muscle aches, sore throat, and swollen lymph nodes. If the disease progresses untreated, it can cause paralysis, among other conditions, and even death.

Physicians are required to report syphilis and congenital syphilis cases to local health authorities. However, many physicians don’t realize Texas law recently changed and now requires pregnant women to be tested for syphilis at three points in time – at their first prenatal visit, in their third trimester, and at delivery, Dr. Shuford says.

Testing for syphilis is complex and can be difficult to interpret, Dr. Eppes says. There are two types of testing – a traditional algorithm and the “reverse sequence” algorithm. Both modes of testing require multiple levels of tests and can show a patient is positive even if he or she has had syphilis in the past, and it has been successfully treated.

Physicians can only know for sure whether the patient has syphilis by looking at symptoms and treatment history, and that can require obtaining past medical records, she says.

“Number one, because these algorithms have changed over time and, number two, because you have to combine the test results with the clinical exam and the treatment history, this is why syphilis testing can be confusing,” Dr. Eppes said in the CME presentation.

Contacting the patient’s previous physician to obtain medical records can be difficult or unproductive in some cases, Dr. Shuford says.

“If [physicians] still can’t get that information, they can reach out to the local health department,” Dr. Shuford said. “Their local and state health departments do have some information available to help clinicians understand when treatment is necessary or what the treatment for a particular patient has looked like in the past.”

Syphilis can be easily treated with one to three doses of penicillin, but the number of doses differs depending on the stage of the disease being addressed, Dr. Eppes says. Some physicians do not prescribe enough penicillin, allowing the disease to progress.

Treating pregnant women also is more complicated than with other patients because they require injectable penicillin, Dr. Shuford says.

“Benzathine penicillin G given intramuscularly can treat both the mom and the baby – it gets into the fetal compartment,” she said. “That is the only treatment we know of that can adequately treat the mom and baby during pregnancy.”

Some patients are allergic to penicillin, raising yet another potential obstacle, Dr. Eppes says. In those cases, patients should go through treatments for desensitization to penicillin so that they can take the medication.

Women who already have difficulty seeing a physician for prenatal visits might have a hard time taking that extra step, Dr. Shuford says.

“Diagnosing and treating syphilis can be really complicated,” she said.

There are other extra steps in treatment that make eradicating syphilis and congenital syphilis especially difficult, Dr. Ramsey says. Patients usually have to inform their sexual partner or partners about the illness and make sure they are treated to prevent a recurrence of the disease. That can be a difficult conversation and is yet another potential obstacle to curing the mother of syphilis.

“Mom acquires syphilis from somewhere, and it’s usually her partner,” he said. “And if we don’t treat the partner as well as mom, we’re not going to eradicate the condition at all.”

Tex Med. 2022;118(6):38-41

July 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page