Houston internist Salil Deshpande, MD, had just finished a grueling residency at Baylor College of Medicine in 2001 when he started taking classes for a master of business administration (MBA) at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

He knew he was shifting gears in his career. Despite the difficulties, Dr. Deshpande has never regretted his decision. He wanted to get into medical administration and policymaking, and the MBA was the best way to do that.

“It opened up very specific roles in the hospital setting and in the managed care setting that I wouldn’t have been able to do,” said Dr. Deshpande, who is chief medical officer for UnitedHealthcare Community Plans of Texas and a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Task Force on Health Care Coverage. “People who pursue this, whether an MBA or [another] alternative degree, are not necessarily turning their backs on medicine or on patient care, and I think it’s important for everyone to realize that.”

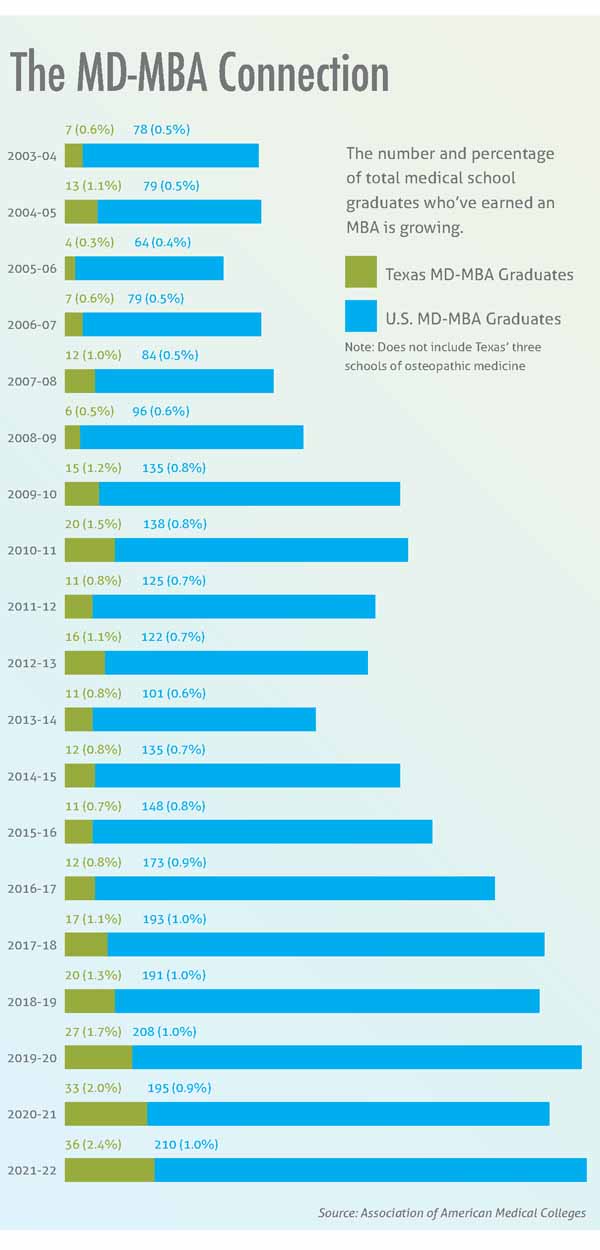

In the early 2000s, a physician or medical student who sought an MBA was pretty exotic. In 2003-04, only about 0.6% of Texas medical graduates at allopathic medical schools and about 0.6% of U.S. allopathic students sought dual MD-MBA degrees, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

MD-MBA dual degrees are still rare, but the numbers are rising. In 2021-22, just over 2% of Texas allopathic medical school graduates obtained those dual degrees, as did 1% of U.S. graduates, AAMC says. (See “The MD-MBA Connection,” right.)

Those physicians – like San Antonio radiologist Rajeev Suri, MD – frequently seek out an MBA to prepare for leadership roles. In fact, Dr. Suri says the executive MBA he obtained in 2020 gave him the necessary tools for his positions as president of the Bexar County Medical Society and interim chair of the department of radiology at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.

He first decided to get an MBA after 14 years in medicine because, like a lot of physicians, he felt lost in the many business meetings he faced. Medical school prepared him well to treat patients, but it didn’t prepare him for the business of medicine, he says.

“When you are sitting in the C-suite talking to the CEO or in any of your practice meetings, the discussions are all business,” he said. “Do you understand profit-loss statements and the finances of medicine? Do you understand organized medicine?”

Most physicians must learn that material on the job, so it takes years, he says. Getting an MBA is neither easy nor cheap, but it does shorten the learning curve.

“You could slug it out and learn [about the business of medicine] over the course of 10 years. Or, you could go through an organized way of learning.”

Since the early 2000s, medical schools have made it easier for students to obtain dual degrees. Some, like The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, work that time into the traditional four years of medical school. Most allow students to put medical school on hold for a year to take an MBA program.

“For the MBA, students typically take a year off between their third and fourth year of medical school and complete the MBA full time in that year,” said pediatrician Angela Mihalic, MD, dean of medical students at UT Southwestern Medical School in Dallas.

Dell Med fourth-year student Ryan Pierson just finished his MBA program. He has already worked as a small business owner and wants to be ready for the business aspects of medicine, whether he runs his own practice or works for an employer.

Before going to medical school, Mr. Pierson was a dietician in the Dallas area, and the demands of staying in business frequently distracted him from helping his clients. Without a formal business education, he had to self-teach with the help of YouTube or Google about important topics like bookkeeping, finance, and business strategy. He frequently discovered things by making mistakes.

“For me it was a huge learning experience because it’s stuff we’re not taught as undergraduates,” he said.

The MBA program helped him understand basic aspects of business, like how to keep a ledger and how to use business vocabulary. It also filled in major knowledge gaps about negotiation skills, the impact of health care reform, and how to assess a business for its strengths and weaknesses.

“The intersection between business and medicine will continue to get stronger in the future,” he said. “I don’t see a way around learning business in the future for clinicians, especially as we take stronger leadership positions.”

Most medical students getting MBAs compress the normal two-year degree course into one year by putting aside business internships and some elective requirements. But they keep core classes on topics like finance, accounting, and business strategy, as well as relevant electives like the finance of health care, says Kristie Pham Tu. She is a fourth-year medical student at UT Southwestern who just finished her MBA at The University of Texas at Dallas.

The skills students learn in an MBA program come in two parts, she says.

“There are the soft skills that you learn – communicating, giving presentations, networking. That stuff is taught implicitly and explicitly,” she said. “And then there are the hard skills – analytical skills with statistics, how to calculate things, what to calculate, what pieces of information are salient to making business decisions.”

Obtaining an MBA may or may not help medical students obtain a residency spot, depending on the needs of the residency, Dr. Mihalic says. But both the soft and the hard skills often come in handy when interviewing for residencies.

“It provides students confidence, knowing how to network and how to approach situations that traditional medical students might not have had with management skills and leadership skills,” she said. “And they have electives in health care management, so they understand the health care system a little bit better and have a greater sense for what’s going on behind the scenes when they go into their residency, which gives them a broader perspective.”

MBAs help physicians obtain leadership roles in part because they provide a better understanding of health policy, says Kevin Bozic, MD, inaugural chair of the department of surgery and perioperative care at Dell Med. He is president-elect of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and will serve in 2023-24.

Dr. Bozic paused his medical career in 2000 to get a two-year MBA at Harvard School of Business shortly after finishing his orthopedic surgery residency – largely because he felt like he knew a lot about treating patients and not much else.

“I heard my colleagues and mentors complaining about our dysfunctional health care system. And I just felt like there was a lot of misunderstanding and miscommunication between physicians and people on the business side of health care,” he said.

Getting an MBA was one way to help overcome that miscommunication.

“I thought of myself as a translator,” Dr. Bozic said. “Because I saw a lot of examples where physicians and administrators were communicating, and the physicians would use lot of big clinical terms to intimidate the nonclinical people, and the businesspeople would throw around a lot of financial terms to try to intimidate the clinicians. I thought if I could learn both languages, I could become bilingual.”

Today, his MBA and the doors it has opened inform much of the work he does as the chair of surgery at Dell Med. For instance, he oversees business development with the start of new clinical programs, and he’s helping to facilitate the transition from fee-for-service to alternative payment models based on value.

Although worth it, these physicians acknowledge that getting an MBA clearly requires a big commitment.

Like many physicians, Dr. Suri could not take off two years from his career to get his MBA, so he took a program at The University of Texas at San Antonio College of Business that allowed him to attend classes on weekends for about 12 hours. On top of that, he spent about two to three hours daily reading course materials.

“You’d force yourself every day after work to finish up your [clinic] work and then take another couple of hours to finish up what needed to be done [for class],” he said.

And Dr. Desphande thought he would zoom right through business school after transitioning from a grueling medical residency, but it turned out to be anything but easy. “The style of education was very different from what my education was like in medical school, so I had to adapt to team-based learning and working with others collaboratively to solve practical problems.”

MBA courses also pose a financial burden that spans a wide range. The University of Texas at Dallas program that partners with UT Southwestern costs about $33,000 for tuition, whereas a student at The Wharton School will pay more than $150,000, according to the schools’ websites. The price of executive MBA programs, typically shorter, can be lower.

But in addition to the business and leadership skills, pursuing an MBA also helps physicians discover fresh points of view.

Most of the 35 people in Dr. Suri’s class worked at one time in fields outside medicine such as banking, insurance, and cybersecurity.

“Getting information from outside medicine and bringing it back to medicine gives you a very new perspective,” he said.