Fourth-year medical student Alyssa Greenwood Francis lost both parents during her first year at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Paul L. Foster School of Medicine in El Paso and worried that taking time off would hurt her career prospects.

Houston pediatrician Alex Yudovich, MD, experienced burnout during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic – when his young, mostly Medicaid patients bore the brunt of its impact – before seeking out employment as a newborn hospitalist.

Austin rheumatologist Brian Sayers, MD, was blindsided as a medical student when his childhood friend and college roommate died by suicide, but he later found solace in faith and spirituality.

These physicians and others shared their experiences with burnout, moral injury, and other stressors during the Texas Medical Association’s Fall Conference on Sept. 17, which was also National Physician Suicide Awareness Day. That same day – and at a pivotal moment for physicians coping with a nearly three-year-long pandemic that has exacerbated long-standing pressures and introduced new ones – TMA debuted its reimagined physician well-being support program: Wellness First.

In fact, after a six-year period of decline, the physician burnout rate spiked in 2021, rising to 62.8% compared with 38.2% in 2020, according to a recently published study in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Taking the step to put physician wellness at the forefront is just another example of how TMA is well-positioned to facilitate the kind of collaboration needed to support physician well-being at the individual, organizational, and systemic levels, says Toi Harris, MD. The Houston psychiatrist is vice chair of TMA’s Committee on Physician Health and Wellness (PHW).

“Previously, the focus has primarily been on individual factors,” she said. “But, in order to really make an impact that will be sustainable, there are also [organizational and] national factors at play.”

Efforts to bolster physician health, for instance, work in tandem with organized medicine’s advocacy at the state and federal levels to mitigate the underlying causes of burnout from other angles, such as through reducing red tape, she says. (See “Root Causes,” page 23.)

And helping physicians take care of themselves helps them to better care for their patients, adds Boerne internist and certified life coach Nora Vasquez, MD, a keynote speaker at TMA’s Fall Conference.

“If we improve physician wellness, we’ll improve the health of all Texans,” she told the audience.

Member physicians already are noticing an impact.

New Braunfels family physician Emily Briggs, MD, commended her colleagues for sharing their burnout stories and TMA for the new program during a question-and-answer session at Fall Conference.

“It really shows growth in our organization to have TMA focus on [physician wellness],” she said through tears.

Dire consequences

During her keynote address, Dr. Vasquez discussed the drivers of physician burnout, which she said are often characterized by feelings of exhaustion, cynicism about one’s job, and a low sense of accomplishment – all of which she could relate to.

As a child, she dreamed of becoming a physician, even though neither of her parents had graduated from college. She said relished the process of making this dream a reality, from her medical school readings to using her Spanish language and cultural competency skills to connect with patients.

But balancing her career and young family led to symptoms of burnout, which she didn’t recognize at first. Instead, she thought something was wrong with her.

“If I was living the dream, why wasn’t I happy?” Dr. Vasquez recalled thinking.

Dr. Vasquez pointed to the sometimes unhealthy culture of medicine as a systemic driver of burnout. For instance, unrealistic workloads and expectations of perfection can cause physicians to feel a lack of control over their professional lives and to compromise their own values.

She added that women physicians are disproportionately affected by burnout. Those with children deal with increased responsibilities at home, which she described as “the invisible load,” as well as specific workplace challenges, such as discrimination, harassment, pay disparities, and fewer leadership opportunities than their male counterparts.

Left unaddressed, physician burnout can have serious consequences.

“It’s an occupational hazard ... when you are exposed to chronic workplace stress,” she told the audience.

Dr. Vasquez cited increased rates of depression, substance use, and relationship problems on a personal level, and higher rates of attrition and lower rates of productivity and quality of care on the professional level. (See “Help, Not Discipline,” page 24.)

Physician burnout also may contribute to long-standing workforce shortages and astronomical health care costs. A March 2022 report by Elsevier Health found nearly half – 47% – of U.S. clinician respondents were planning to leave their current role within the next two or three years.

Another study, published in the April 2022 issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings, found primary care physician turnover accounted for nearly $1 billion in excess health care spending in the U.S., with nearly a third of that cost attributable to physician burnout.

Changing attitudes

Even amid the dark clouds of these concerning trends, physician speakers at Fall Conference emphasized the importance of physicians talking about these difficult topics, as well as increasing the number of resources available to help them regain equanimity, during an emotional panel moderated by Austin adolescent behavioral health specialist Celia Neavel, MD.

Dr. Sayers, who chairs Travis County Medical Society’s (TCMS’) Physician Wellness Program, spoke about the impact of his friend’s death and other personal burdens – including a childhood impacted by “family alcoholism” – that combined with work pressures to put him in distress.

“I was in the wilderness,” he said. “When we’re in the wilderness, each of us has to find a way out.”

Dr. Sayers’ path included five years of study at an Austin seminary and becoming involved with physician wellness initiatives.

Over his many years studying physician health and leading the TCMS program, he has seen attitudes toward and research about physician burnout shift.

In the past, most accepted wisdom focused on internal factors, including physicians’ tendency toward perfectionism, he says. Now, the literature around physician burnout often points to systemic problems, including increasing demands for high-volume care and heightened administrative burdens.

“That shift is not surprising because there’s been, in the same time frame, a big shift from physicians being self-employed or in small groups to the vast majority being employed,” he told Texas Medicine.

While programs like TCMS’ are limited in their abilities to directly address physicians’ workplace woes, Dr. Sayers says it aims to help physicians find balance.

“We can’t put food on people’s tables if they’re in a job that they’re stuck in,” he said. “But we do want to help people explore those [support] options and not feel ashamed of dropping out of a job that’s injuring them.”

Since its inception in 2017, TCMS’ wellness program has developed educational resources and hosted events, thanks in part to grant funding from the TMA Foundation. It also launched a confidential counseling service that has provided more than 1,500 sessions to more than 350 physicians in Travis County.

TMA’s Wellness First can connect physicians to similar county medical society programs around the state. (See “Local Support,” page 16.)

Dr. Sayers says these counseling sessions can help bolster physicians in the face of work and personal challenges, which often feed into each other. In some cases, TCMS provides couples counseling. In others, its programming fosters community and connection, which he says are powerful antidotes to burnout.

“We do spend a lot of time and effort addressing the things that come downstream in people’s lives from being in a work environment that’s relentlessly hard on them,” he said.

He also celebrates his younger colleagues, whom he says prioritize wellness and work-life balance more than their predecessors. By contrast, he describes his own medical training in the 1970s and ’80s as “intimidation-based,” which left little room for students and residents to push back or develop habits around work-life balance. “The generation that’s coming through training now, thankfully, has better expectations for what they want their lives to be,” Dr. Sayers said.

Research bears this out. Nine out of 10 millennial physicians – between the ages of 26 and 41 in 2022 – reported it was important to strike a balance between work and personal responsibilities, according to a 2017 survey by the American Medical Association.

Dr. Sayers also notices this generational shift when parsing the counseling service’s anonymized data. The vast majority of clients are under age 40, he says, and two-thirds are women, who are more likely than their male physician counterparts to report burnout.

Ms. Greenwood Francis spoke about medical schools’ growing focus on student wellness and encouraged the audience to seek help during their own personal traumas.

“My story’s not unique,” she said. “We have to make spaces for us to talk about this.”

Following her parents’ deaths, Ms. Greenwood Francis said she struggled with imposter syndrome, which brings with it feelings of self-doubt and fears of being a fraud. When she raised the issue with a physician supervisor during training, she was comforted to learn she was not alone and that others had found ways to manage such worries.

“You have to learn how to cope with it,” she said, adding that the earlier medical students and physicians develop such strategies, the better positioned they’ll be to deal with challenges throughout their careers.

Through life coaching, Dr. Vasquez learned she was, in fact, experiencing burnout and developed new skills to mitigate its impacts. Now, she is the CEO of her own physician coaching service, Renew Your Mind MD. She also developed Bexar County Medical Society’s Physician Coaching and Wellness Program, where she leads a free monthly webinar series focused on evidence-based coaching strategies to enhance physician well-being.

Dr. Vasquez also discussed how health systems, medical associations, and residency programs are increasingly offering coaching programs – to positive effect.

She pointed to a clinical trial of 88 physicians that found professional coaching significantly reduced emotional exhaustion and other symptoms of burnout while also improving quality of life and resilience. Cleveland Clinic officials also estimate the health system saved at least $133 million in physician retention in 2020 thanks to a clinician coaching program, as reported by Becker’s Hospital Review.

“This work literally saves lives,” Dr. Vasquez said.

Institutional improvements

Dr. Harris has focused on the organizational level in her dual roles as vice chair of TMA’s Committee on Physician Health and Wellness and as chief equity, diversity, and inclusion officer of Memorial Hermann Health System.

She says TMA’s access to physicians, medical schools, residency programs, and employers makes the association an important convener and collaborator.

The PHW Committee, which started out in 1976 to help impaired physicians (such help is still available via TMA’s Physicians Benevolent Fund, page 20) has since evolved and developed approximately 40 health and wellness CME courses physicians can connect to via Wellness First.

The committee also spearheaded the inaugural Physician Health and Wellness Exchange in 2019, a statewide collaboration that brings together academic medical centers and county medical societies to:

- Share best practices for fostering health and wellness among medical students, residents, and physicians;

- Support health and wellness professionals; and

- Establish a forum for collaboration to advance research.

TMA hosted a virtual PHW Exchange in 2021 and is planning a third, biennial event in 2023.

The activity also aims to empower institutions to root out physician burnout among their staff and faculty. Dr. Harris expounded on this in a 2021 article published in Medical Education Online, which documented the emergence of the PHW Exchange.

“Individual strategies in isolation are insufficient,” she and her co-authors wrote. “In addition to policies and programming to address burnout in medical students, trainees, and physicians, attention to external forces, as well as the entire learning system and its members are key.”

At Memorial Hermann Health System, Dr. Harris works to cultivate a workplace where physicians and other health care professionals feel valued. This, in turn, can help assuage physician distress and attrition.

“We’re striving not just to provide health care [for our patients] but for our entire community to be healthy, and that includes those who work and train in our spaces,” she said.

Dr. Vasquez hinted at this interconnectedness during Fall Conference.

She asked physicians to consider burnout as “a blessing in disguise,” one that could compel medicine to prioritize a culture of wellness. She also commended TMA for taking up this mantle, citing the toll of COVID-19.

“Some of us have lost patients, have lost family members,” she said. “Some of us are losing hope.”

Struck by the emotional conversations in the room, Keller pediatrician Jason Terk, MD, shared his own story of burnout – and how leaning on the Family of Medicine helped him recover.

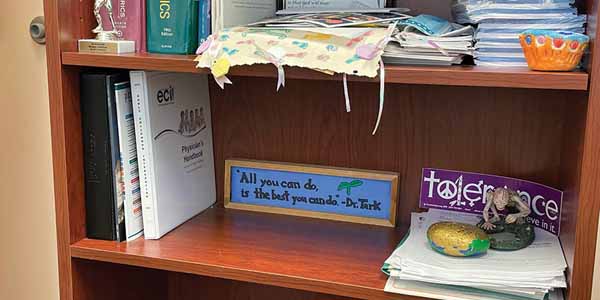

Years ago, he had fielded a question from a student during a preceptorship. She had asked how he handled the constant demands of being a physician and how he knew he’d asked all the right questions. She later emblazoned his answer on a wooden memento, which he displays on a shelf in his office.

Recently, Dr. Terk struggled to maintain his own emotional balance after a colleague died by suicide. After a career “sucking the marrow out of every positive moment,” he said, his reserves were depleted. But he found solace in his own advice, which was staring back at him.

“All you can do is the best you can do.”