Over Douglas Curran, MD's 40-year span as a family physician in Athens – where the uninsured rate at 23% is higher than the state average – he didn’t mind receiving pecan pie as a form of payment.

“I took care of a lot of people without insurance, who didn’t have any money, and I don’t regret any of that,” Dr. Curran said. They also paid in tomatoes, eggs, chickens, and steaks. “We enjoyed those treasures from our patients,” he recalled, but understood that pecan pie wouldn’t keep the lights on. What’s more, without changing the system, without a true medical safety net, his patients would never truly be well.

Early in his career, Dr. Curran began working to persuade state lawmakers to increase access to affordable health care coverage. Over the years, he has served as a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Select Committee on Medicaid, CHIP, and the Uninsured; Select Committee on National Health System Reform; and Task Force on Health System Reform. When he served as TMA president from 2018 to 2019, he made it his mission to champion reforms to the state Medicaid program and find ways to extend health care coverage to as many as 1.6 million working people who don’t qualify for Medicaid or subsidies under the federal insurance marketplace.

Unfortunately, the Texas Legislature passed on the idea. Texas remains one of a dozen states that have still not opted to expand Medicaid as permitted under the Affordable Care Act.

“Such inaction has driven up health care costs and closed down at least 25 rural hospitals,” Dr. Curran said. On his 238-acre ranch, he has better luck finding consensus with his Black Angus cattle and Wagyu bulls. (“The Wagyu/Angus cross is just delicious,” he said.)

In 2019, Dr. Curran and his business partner, Ted Mettetal, MD, retired from Lakeland Medical Associates, the practice they founded more than 20 years ago. But they never shook the idea of finding a way to expand access to care in the area.

Believing collaboration was the right path, Dr. Curran persisted in finding a solution for his community. He found it in the form of a federally qualified health center (FQHC) he and his private practice partner have set out to create with enthusiastic local support: East Texas Community Clinic.

“I’m convinced when you take care of people, whether they have or have not, and you do right by them, that’s honorable work and gets recognized,” Dr. Curran explained, summing up the secret to his successful career in private practice. “When we work together as physicians to take really good care of our patients, we’re doing what we were built to do.”

Many of Dr. Curran’s good ideas come while walking with Dr. Mettetal. “We call his front porch the ‘birthing center’ because that’s where we start and stop our walks,” Dr. Mettetal said. And that’s where those ideas incubate – typically while drinking a bottle of Hope Springs Water produced by the nonprofit born on that porch in 2010 by Dr. Mettetal. Hope Springs Water has since brought clean water and sanitation to more than 100,000 people in 12 countries.

In the fall of 2019, as they walked and talked, they discussed the impending merger of The University of Texas at Tyler and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler. A year prior, UT Health East Texas had bought the East Texas Medical Center in Tyler. There were plans for a new medical school, which would need residency positions.

“Being in a rural community with a full-scope family practice as its base, we thought we could train young family docs, who would then hopefully stay in rural Texas,” Dr. Curran said. The way to both build the residency program and serve an indigent patient population, they decided, was to create an FQHC.

At the end of their four-mile walk, the East Texas Community Clinic was born.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, an FQHC is an important safety net in rural areas. These outpatient clinics qualify for specific grant funding and prospective Medicare and Medicaid payments meant to help them cover their costs while providing a robust set of services to the uninsured. There are two tiers before gaining FQHC status: Health Center Program Award Recipient, which receives grant funding from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration; and Health Center Program Look-Alike, which meets all of the criteria of an FQHC and puts the clinic in line for final approval. The benefits of these designations include reduced prices for medications, access to the Vaccines for Children program, and medical liability coverage.

Along with additional funding, Dr. Curran says the FQHC status would provide stability to the clinic while serving as “a launching pad for relationships that will help us train more ambulatory care primary physicians.”

With his former practice manager, Glen Robison, as the new clinic’s CEO, Dr. Curran set out to learn as much as he could about FQHCs. They traveled to Dallas to tour the Los Barrios Unidos Community Clinic, and then to Waco to show potential financial partners the Heart of Texas Community Health Center, which was established more than 30 years ago.

Dr. Curran says their guests wanted to know: Can we do this? “Absolutely, we can,” he told them.

Meanwhile, they began securing funding, which came from for-profit Ardent Health, the Murchison Foundation, and the East Texas Medical Center Foundation. The physicians from their former practice, Lakeland Medical Associates, bought a 1,900-square-foot building in Gun Barrel City to lease back to them. After remodeling the former accounting office, East Texas Community Clinic opened its doors in May 2020 and treated 47 patients in its first week.

As the primary care clinic was preparing to open, the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading across the world. While the two retired friends walked and talked, Dr. Mettetal recalls saying: “You know, Doug, here we have the greatest health care crisis in our lifetime, and we’re standing on the sidelines. We have to get back in the game.”

Drs. Curran and Mettetal came out of retirement to volunteer at the clinic, alternating three days a week. The clinic not only offered care to more than 57,000 uninsured residents in their three-county area but also provided relief for the UT Health East Texas emergency department at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

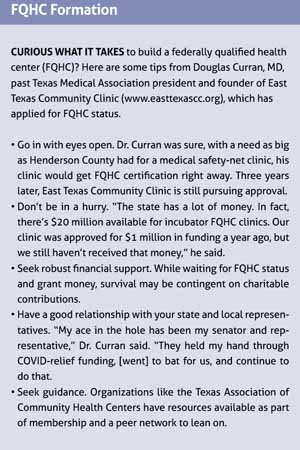

In January 2021, Mr. Robison submitted a 234-page application for FQHC status; three months later the request was denied. “It was hard not knowing the process or having a roadmap to set up an FQHC, but it’s also been fun,” he said. “I hate being told no, so it makes me push even harder to move forward.”

By then East Texas Community Clinic had treated some 7,000 patients. There was no stopping now. Mr. Robison was up to the challenge. The physicians opened a second location in Athens in June 2021 after Ardent Health donated the 7,000-square-foot space. In July, the first four of 12 residents began training.

“Glen and I were adamant that it was going to be the nicest clinic in town. First rate,” Dr. Curran said. “That came out of wanting to be sure that while providing care we also treated patients with dignity and respect as human beings. As a result, they come in droves.”

For now, the clinic, whose population is 70% on Medicaid or having no insurance at all, is getting paid the same way a regular office would, billing Medicare and Medicaid. Its survival is contingent on donations from organizations that have bought into what it’s doing.

Mr. Robison says running the clinic is the reverse of running a private practice clinic, where administrators have to ration Medicaid patients to stay in business. “It’s rewarding to see these patients actually get their care.”

Dr. Mettetal concurs, noting how appreciative patients are. “We still have people say, ‘We’re so glad you opened this clinic; I haven’t seen a doctor in 20 years or 30 years.’”

By the end of 2021, patient visits were up to 15,000. The clinic hired three new doctors and had eight medical residents. With such growth, Dr. Curran was intent that East Texas Community Clinic not compete with private practices but help them flourish.

He wants to treat the subset of patients private practice groups can’t take care of without going broke. “[An] FQHC doesn’t turn anyone away. If they need to be seen, we see them,” he said. Then private practices can focus on patients who can pay.

“Everybody wins. And that’s the goal,” he said. “If I can get FQHC grants and support, then I don’t need to be taking [private] insurance patients. I’d rather my colleagues see those patients. Collaborating with my colleagues always turns out better.”

Mr. Robison resubmitted the FQHC application in March 2022, this time with the assistance of the Texas Association of Community Health Centers. The clinic is preparing for a site visit in mid-December to reach that next tier and become an FQHC look-alike clinic.

“I have an appreciation for why there isn’t an FQHC on every corner,” Mr. Robison said. “Anytime you put federal or state in the title, it comes with a lot of rules and regulations. But I understand the need for those processes, and it will be worth the effort.”

Once the clinic gets that look-alike status, it will receive federal funding similar to an FQHC. “But we won’t yet be eligible for grants and funding opportunities, and we want a full FQHC to support the residency program, be a more functional clinic and an anchor for other residency programs,” Dr. Curran said. But to get that distinction, Congress has to approve money to establish more FQHCs. “We’re in limbo until that happens.”

Dr. Curran says what’s important is staying true to his profession – true to his goal to work together to take good care of patients. By establishing a network of physicians, providers, and donors, he has successfully woven a medical safety net for this pocket in East Texas. “This collaborative spirit is what we ought to have. When we do that in our community, then we change the world.”