The latest biennial survey of maternal death and illness shows why the Texas Medical Association made improving maternal health one of its top priorities for the current state legislative session.

The report found that Texas still does not adequately protect the health of women in their childbearing years – especially Black women. Based on preliminary 2019 data, the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee (MMMRC) found 59 pregnancy-related deaths – those caused directly or indirectly by the pregnancy. Those 59 cases were identified from a larger pool of 140 deaths identified as pregnancy-associated, meaning they occurred during a pregnancy and up to one year afterward.

For each pregnancy-associated death, there are at least 100 other women who represent a “near-miss” – a person who has severe, often life-altering complications but does not die, says Houston obstetrician-gynecologist Carla Ortique, MD, chair of MMMRC.

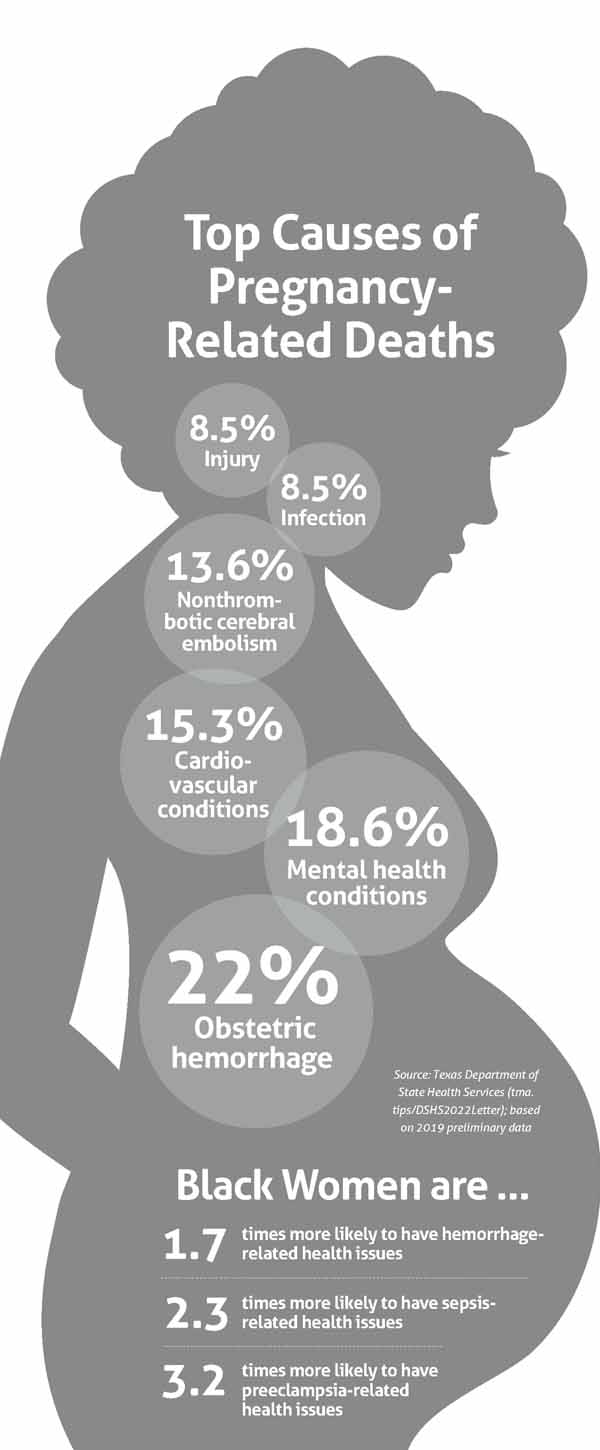

Moreover, 88% of the pregnancy-related deaths were deemed preventable, according to a follow-up letter the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) sent to Gov. Greg Abbott. DSHS oversees the maternal review committee. (See “Top Causes of Pregnancy-Related Deaths,” below.)

“That number should be zero,” Dr. Ortique told MMMRC when it met in December 2022 as the initial report was released. “We should not die of causes that are preventable.”

Many maternal deaths are preventable because of problems tied to health care, but nonmedical issues also play a large role, says Houston OB-gyn Rakhi Dimino, MD, chair of TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health.

“Many people may think that we must be having trouble in every hospital if we’re having nearly 90% potentially preventable deaths,” she told Texas Medicine. “But this report is really a comprehensive look at all the contributing factors to maternal death. That includes physicians and birthing facilities, but also community issues, barriers to access to care, socioeconomic factors, and other challenges that may prevent the best overall care.”

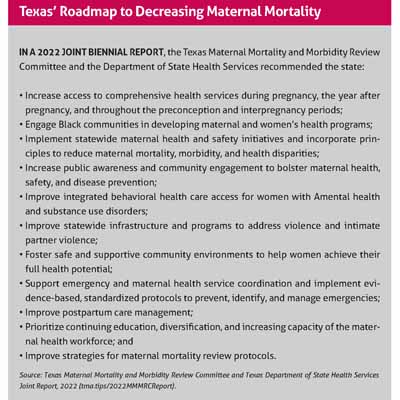

The report’s top recommendation calls for Texas to increase the availability of comprehensive health care coverage during pregnancy, the year after pregnancy, and throughout the time women are able to bear children. (See “Texas’ Roadmap to Decreasing Maternal Mortality,” below.) One of TMA’s top priorities for the 2023 legislative session is to extend coverage of Medicaid postpartum care from two months to 12 months.

In a departure from previous MMMRC reports, the 2022 findings emphasize the problems faced by Black women, Dr. Ortique explained in an interview with Texas Medicine. Data collected by MMMRC over time show that Black women are disproportionately affected by maternal death and illness.

The exact reasons Black women face higher rates of maternal death and illness remain unclear and are being studied by MMMRC’s Subcommittee on Maternal Health Disparities. The 2019 numbers also show that non-Hispanic Black women die at twice the rate of non-Hispanic white women and more than four times the rate of Hispanic women. That trend has persisted since at least 2013, the earliest year with data available.

To address this issue, MMMRC’s second recommendation calls for the state to “engage Black communities and those that support them in the development of maternal and women’s health programs.” This includes bettering maternal health and safety programs and services aimed at Black women; redesigning graduate medical education to help physicians better address disparities in care; and implementing policies at hospitals and clinics designed to promote more respectful care.

“If we solve that problem, we would see our overall [morbidity and mortality] rates decline as well,” Dr. Ortique said.

The report points to the role of bias as one factor in the elevated death and illness rates for Black women, and in many cases that bias is subtle, Dr. Dimino says. For instance, if a physician writes in a patient’s chart that the patient is “noncompliant” with treatment because she hasn’t shown up for appointments, that might cause other staff members to believe the mother lacks interest in her own health or the health of her baby.

“If the reason she didn’t go to her specialist appointment downtown is transportation, we should say the barrier is transportation,” she said. “We should then work to overcome that barrier instead of implying that she is simply skipping her appointments. Documenting ‘noncompliant to care’ may make other care providers believe she is a ‘bad’ patient, so they are more likely to write her off.”

Preventing maternal death and illness overall has become more difficult since COVID-19 began spreading widely in the U.S. in March 2020 because the pandemic exacerbated already existing staffing shortages among physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals, Dr. Ortique says.

The problem has become especially acute in obstetrics and gynecology because, since the June 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Texas physicians and many of their patients have been in a medical limbo.

The decision set in motion state law that imposes additional abortion restrictions. The vague and sometimes inconsistent requirements laid out in Texas law make it difficult for physicians to work with patients when complications arise before birth.

The lack of clarity about how to treat patients has made it more difficult for medical practices and institutions to recruit OB-gyns to fill open positions, Dr. Ortique says.

“Recent legislative changes have made our state not appealing,” she told the MMMRC meeting in December. “It used to be that you were running to Texas to get trained, to do your residency, to go to medical school, to go to nursing school. But now people are moving out, and we’re not attracting the top talent to our state.”

The report does include good news, says San Antonio OB-gyn Patrick Ramsey, MD, vice chair of MMMRC. For instance, while obstetric hemorrhage was the leading cause of maternal deaths, hemorrhage hospitalizations in severe cases of illness declined to their lowest level since 2017, to 27.5 deliveries per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations.

This decline in morbidity from hemorrhage coincided with the introduction of the Texas Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM). TexasAIM provides a “bundle,” or collection of best practices, for treating hemorrhage that was used in 98% of Texas birthing facilities starting in 2019.

“That shows at a high level some of the interventions we’re doing in response to prior reports may be having an impact,” Dr. Ramsey said.

Even here though, Black women faced bigger obstacles than other women, Dr. Dimino says. While the overall rate went down, among Black women, severe illness caused by hemorrhage rose by 9.8%.

“We still have a good amount of work to do,” Dr. Dimino said.

And while the drop in hemorrhage deaths is encouraging, those deaths also are a sign that some birthing facilities still need to work on their hemorrhage treatment, says Houston OB-gyn Catherine Eppes, MD, a member of TMA’s Committee on Reproductive, Women’s, and Perinatal Health and of MMMRC.

Texas is the only state to require that all personal information – including the facility that helped a woman give birth – be redacted from a medical record before MMMRC can review it. That makes it impossible to know which birthing centers are still struggling to treat hemorrhage, Dr. Eppes says.

In addition, medical records often are hundreds of pages long, so the editing process greatly slows down collecting data on maternal deaths and illness, Dr. Ortique says.

“Maternal death records are often voluminous,” she told Texas Medicine. “So going through every page to remove any identifying information is very tedious and time consuming.”

MMMRC’s reporting on 2019 maternal deaths and illness came in stages and would have been faster without the redaction process, Dr. Ortique says. The report initially reviewed 118 cases preliminarily identified as pregnancy-associated deaths. Then between September and December 2022 – after the report’s completion – MMMRC finished reviewing an additional 22 cases, bringing its analysis to a total of 140 cases, according to the DSHS letter. Seven additional cases were under review as Texas Medicine went to press.