Small and solo physician practices today are not unlike the independent bookstores that felt the pressures of viability during the rise of major chains like Barnes & Nobles and the disruption of Amazon.

Consolidation in health care has followed a path similar to that of other industries, such as commercial banking and car dealerships, creating new opportunities – and challenges – for physicians as well as for organized medicine.

And inquiring physician businessowners want to know how they can chart a similar path toward survival and success.

For Texas Medical Association President Rick Snyder, MD, that meant accepting private equity investment so his 53-physician cardiology practice could maintain its independence from regional hospitals while growing its staff to serve more patients and scale its business, now across 20 locations in the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area.

For Sue Bailey, MD, a Fort Worth allergist and immunologist in smaller private practice, the hurdles look different.

“A typical nonmedical small business is able to find ways to increase volume or to branch out into other potential sources of income in order for their business to grow or even to survive,” said Dr. Bailey, co-chair of TMA’s Ad Hoc Committee on Independent Physician Practice. “But an independent practice does not have that luxury. … It’s not like I can do surgeries on the side to increase my income.”

Still others like Longview internist Brenda Vozza, MD, are finding ways to navigate those winds to their advantage, even in rural, underserved areas that may lack the obvious opportunities found in metros.

Though she had to wait until accountable care organizations (ACOs) made their way to her area, she eventually joined one. “It’s been a great journey,” the member of TMA’s Task Force on Alternative Payment Models (APMs) said. “I’m much more enabled to provide good care for my patients because of [value-based care], and I have more support than I did 10 years ago.”

The bottom line: Despite shifting economic headwinds, physicians have options, even more than before, says TMA CEO Michael Darrouzet. They can choose to remain in small or solo private practice; seek to grow their group by accepting outside investment; join a physician-owned ACO; or sell their practice to a hospital, health system, or insurer.

“There’s no wrong way to do this,” he said. “Physicians are being creative about it.”

And TMA is here to help practices thrive, remaining steady in its advocacy at the state and federal levels to protect physician autonomy and to defend against the corporate practice of medicine. (See "Judgment Calls," page 24.) As the business of medicine evolves and diversifies, so too has the work of organized medicine. With the help of physicians like Drs. Snyder, Bailey, and Vozza, TMA is developing new, targeted resources to help physicians across practice settings and payment models.

“We empower physicians, and we empower the patient-physician relationship,” Dr. Snyder told Texas Medicine. “We’ve got to make sure they’re empowered in any [practice or payment] model.”

Dr. Snyder attributes deepening health care consolidation to several factors.

Inflation and rising costs squeeze physician practices’ already-thin margins, which he says incentivize growth because bigger practices have more leverage when negotiating with health plans and can benefit from economies of scale.

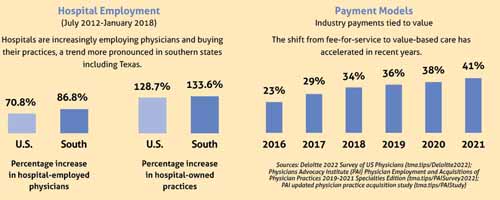

Larger groups also stand to reap the financial rewards of new payment models, notably value-based care arrangements, which require start-up investments in case managers, technology, and data analytics, for instance. But to solo and small practices, this proposition can seem out of reach, especially as they contend with other market forces, including worsening administrative burdens and a tight labor market.

As consolidation continues, Texas physicians increasingly practice in a plethora of settings, depending on their unique needs.

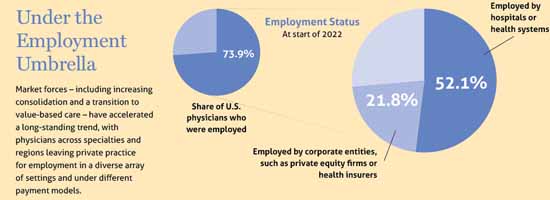

Nearly three-quarters – 73.9% – of U.S. physicians found themselves in various types of employed positions by the start of 2022. (See “Under the Employment Umbrella,” page 16.)

Employment encompasses many practice settings and ownership structures, including those headed by hospitals, insurers, and private equity firms. Of course, many physicians continue to practice solo or in small groups. And, as Dr. Snyder points out, the health care industry is constantly in flux, with new players such as Amazon and Walmart seeking to acquire physician practices for their own retail medicine outfits, paving yet another path for which physicians may opt.

Mr. Darrouzet says this upheaval is the byproduct of American capitalism.

“If you’re small and you have some value, somebody bigger is going to offer you a price, or they’re going to try to take you over,” he explained. “That’s just the way the economy works. And it’s starting to happen in medicine.”

Despite these economic hurdles, Mr. Darrouzet says consolidation also has catalyzed the creation of new practice models.

This is thanks in part to the Affordable Care Act, which, when it became law in 2010, established ACOs – voluntary groups of physicians, hospitals, and other health care organizations that accept responsibility for the overall quality, cost, and care of a defined group of patients.

Mr. Darrouzet says the physician-designed value-based care arrangement was “revolutionary” because it offered physicians a new option amid increasing consolidation, a way to affiliate with other physicians and hospitals – enabling growth – without merging. ACOs also relieved some of the antitrust pressures that tended to discourage collaboration among physicians and others for fear of being accused of collusion.

Mr. Darrouzet acknowledges that addressing the needs of a diverse TMA membership is easier said than done “because the needs of the very large groups, which tend to lean toward value-based care, … and [of] small practices are very different.”

But TMA is on task with its newly founded Ad Hoc Committee on Independent Physician Practice and Task Force on Alternative Payment Models representing a wide swath of physician practices and experiences, among other resources in the works.

Smaller, private physician practices, for instance, face the same threats as their larger counterparts: successive physician pay cuts, fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising inflation, to name a few. But they lack access to the same tools when dealing with them.

TMA is dedicated to helping them keep their doors open, which led to the creation of the Ad Hoc Committee on Independent Physician Practice, says co-chair Dr. Bailey.

Between 2019 and 2020, more than 48,000 U.S. physicians left independent practice, according to the Physicians Advocacy Institute, with the trend more pronounced in southern states, including Texas. (See “Under the Employment Umbrella,” above.)

Dr. Bailey says physicians operate in an inflexible regulatory and payment environment, which can limit their defenses against economic headwinds. So, the committee is charged with identifying the needs of private practices when confronting these challenges – and others – and with developing possible solutions. Its members aim to provide resources for students, residents, and young physicians interested in private practice – and also worried about whether it’s a sound financial decision.

“The transition between being independent and being employed, or vice versa, has some special nuances that physicians need help with,” she said.

To this end, the committee also wants to support established physicians who are struggling to keep their practices afloat or who are in employed positions and seeking an alternative.

This last scenario, she says, “can feel like jumping out of a perfectly good airplane without a parachute.” But Dr. Bailey and the group’s other members want to ensure these physicians can make “a soft landing,” whatever their destination.

Jumping from fee-for-service to value-based care may be one of those landing targets, with public and private payers introducing myriad new payment models in recent years. (See “What’s New in Value-Based Care,” July 2022 Texas Medicine, pages 12-18.)

But many physicians find the variety of plans overwhelming.

So, the TMA Board of Trustees approved last year the formation of a Task Force on APMs to ease this transition and to ensure plans treat physicians fairly. Its diverse membership – which spans specialties, experience levels, practice types, and geographic regions – is charged with reviewing value-based care trends, prioritizing members’ needs, and advocating for policy and regulations that protect physicians in these arrangements.

Ken Hopper, MD, a psychiatrist in Fort Worth and a member of the task force, began practicing value-based care in the mid-2000s, when he oversaw integrated mental and behavioral health care management programs on behalf of an insurance company.

By treating patients with depression in a primary care setting, for instance, the programs minimized the use of specialists, containing costs; spared physicians the work of case management, freeing up their time for direct patient care; and allowed for close patient monitoring, driving positive outcomes and feedback.

“Everything I had done around integrating behavioral care into medical care had to have [a return on investment],” he said.

Dr. Hopper says this experience taught him how to thrive under value-based care models, knowledge he soon applied to his own practice. He’d like the task force to help physicians realize these same gains, in part by arming them with the business acumen necessary to do so.

“There are strong models that put physicians more in control of the clinical setting … and force them to be creative with the money they’re given,” he said.

Dr. Vozza tried several value-based care arrangements before settling into one that works well for her and her practice. She initially got involved via Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) but soon sought out an ACO, eager to move away from what she describes as MIPS’ arbitrary measures.

Her performance was measured, in part, by the percentage of her patients in a certain age range – 50 to 75 – whom she had screened for colon cancer. But some patients, like one undergoing treatment for metastatic cancer, understandably didn’t want to submit to the procedure.

“There was no way to exclude people from the denominator,” she said.

Dr. Vozza had to wait a few years, though, until ACOs spread to her area, to escape MIPS. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic helped usher in regional and national ACOs, aided by technology, and she’s now a member of a totally virtual organization.

Given her experience, Dr. Vozza hopes the task force can help physicians navigate this search process, similarly to how TMA offers resources for physician practices sorting through electronic health record vendor options. She also enthusiastically embraces the task force’s advocacy to improve the measures Medicare and other payers use, which she says could stand to become more patient-centered.

Dr. Snyder points to the committee and the task force as key ways TMA is supporting Texas physicians, regardless of where and how they practice. But he acknowledges that this work will continue to evolve, alongside physicians’ needs and the market, even as TMA’s north star remains constant.

“We’ve got to continue to be on guard for physicians and the physician-patient relationship,” he said.