Steve Steffensen, MD, is a regular patron of the Texas Medical Association archive.

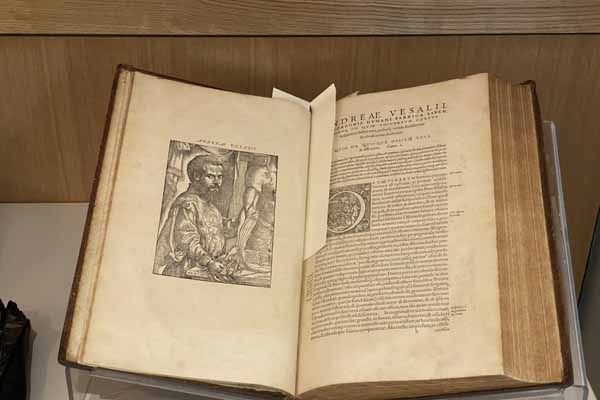

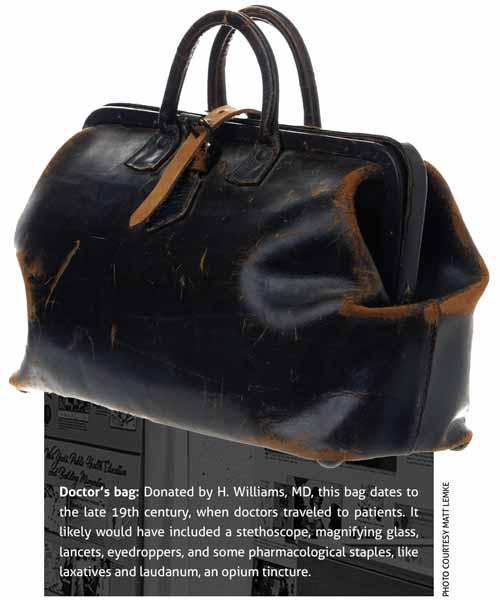

Each year, the associate professor of neurology and population health at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School borrows items therein – an older doctor’s bag, wax anatomical models, a stereoscope – to share during his neuroanatomy course for first-year students. The biggest draw is one human anatomy book of a seven-volume 1555 edition of Andrea Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica, based on the author’s dissections that built on the work of Aristotle and Galen.

“They won’t remember the online textbook that I use in my class, but they’ll remember feeling the pages of the Vesalius,” he told Texas Medicine. “It’s really special to me to be a part of that.”

Dr. Steffensen, a member of TMA’s History of Medicine Committee, says anatomy, as depicted in medical atlases, hasn’t changed much since the 16th century; many historical texts remain relevant. Perhaps more importantly, such objects help orient students as they embark on their own medical journeys, serving as proof of all the others who paved the path before them – and probably also struggled to learn the intricacies of the human body.

“Holding an old book or an artifact of medicine, you get a tactile response that proves that you’re part of this legacy of medicine,” he said.

TMA’s archive dates back almost as far as the association itself, which was founded in 1853. During his 1904 TMA presidential term, Frank Paschal, MD, prioritized the preservation of Texas’ medical history.

“The labors of this association should always be conserved, and unless steps are taken the past work will be lost forever,” archive documents record Dr. Paschal telling the House of Delegates in his inaugural address.

Since then, TMA has collaborated with UT Austin to document the state’s medical and medical association histories, began accepting relevant artifacts and collections, and established its History of Medicine Committee. (See “Making the Past Present,” page 12.) More recently, the archive weathered TMA’s 1991 relocation to its current headquarters at the Louis J. Goodman building in Austin and the advent of the internet, which revolutionized how information is shared and preserved.

Today, TMA’s archive remains a vital resource for member physicians, medical historians, genealogists, and educators as well as TMA boards, councils, and committees, which lean on documented precedent when crafting internal policy. To ensure this legacy, TMA continues to digitize key elements of the archive. Meanwhile, ongoing renovations of TMA’s headquarters include a new physical home for the archive – atop reinforced flooring that can bear the weight of this history – and display cases for select artifacts.

TMA President Ray Callas, MD, says the archive plays an important role in fulfilling TMA’s mission to empower Texas physicians in the practice of medicine. Without a sense of history, TMA’s leadership could be doomed to repeat past mistakes and forget past successes. (See “Changing History,” page 24.)

“It’s very important for us to preserve all history, no matter if it’s been good or bad or indifferent,” he said. “It gives you a path of where things used to be ... and where [they] could go in the future.”

TMA sources archival materials from a diverse range of sources that appeal to a diverse range of users.

Member physicians and their families have made the collection what it is today, says Heather Bettridge, TMA’s associate vice president of practice and information services.

For instance, Kurt Lekisch, MD, a public health specialist who was born in Germany and later settled in Austin, amassed a 188-volume medical stamp collection. Dr. Lekisch’s wife, Dorie, donated the collection to TMA after his 1944 death. Stamps from various countries include physicians, like Sigmund Freud, from the former République du Mali, and Elizabeth Blackwell, from the U.S.; public health campaigns, like global malaria eradication, from Ghana; and plants with potential medical properties, like poppies, from the former Czechoslovakia, and belladonna, from the former Yugoslavia.

The chain of custody for other artifacts, like an iron lung from the former University Medical Center Brackenridge in Austin and post-mortem dissection kits dating back to the Civil War, is more complicated or has been lost to time.

Nonetheless, the objects remain a draw for many member physicians and the public, who look to the past to educate and inform.

They include Gordon Green, MD, a retired pediatrician, who co-edited the DMJ100, published in 2016 to celebrate the Dallas Medical Journal’s centennial. Each issue, the Dallas County Medical Society (DCMS) president would write a letter to readers. Dr. Green and his co-editors, including Richard Joseph, MD, a retired obstetrician-gynecologist, relied on these letters to mark significant events, from the dangerously fast-growing fad of smoking, which then-DCMS President J.M. Martin, MD, opined on in 1929, to the rising costs of health insurance to the AIDS epidemic.

“Those presidential writings are a rich tapestry of what has gone before us,” Dr. Green said. “It is so interesting how people from a half a century or a quarter century ago viewed the situation in the practice of medicine.”

Brad Holland, MD, an otolaryngologist in Waco and speaker of the TMA House of Delegates, relied on such insights during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Turning to the archive, he pieced together a roadmap using house transactions and other ephemera from 1918, when another pandemic – Spanish flu – ravaged the nation.

“It was both comforting and sobering,” he said.

The archive also includes records of other watershed moments, such as TMA’s creation of a bylaw provision giving TMA’s Board of Trustees emergency power to function as a Disaster Board and assume certain responsibilities of the House of Delegates, such as elections and decision-making.

Citing these examples, Dr. Holland says the archive benefits TMA member physicians and the public.

“I fear that kind of information could be lost if there wasn’t something like TMA and its archives to cultivate and curate it,” he said, adding “it gets people excited about TMA [because] they’re not getting that history from anywhere else.”

More than a century after its inception, TMA’s archive is undergoing two major changes: an ongoing digitization process and the renovation of TMA’s headquarters. Both will ensure the archive remains accessible and fruitful for future generations.

The digitization process began in 2005 and spans partnerships with other venerable institutions, like the Medical Heritage Library at Harvard University. (See “Archival Resources,” page 22.)

TMA’s History of Medicine Committee helps identify archival categories for digitization. As documents are scanned, they can be accessed via the TMA Knowledge Center; some also are available online.

“It just opens up a whole new world and really is ... the modern way of preservation,” Dr. Holland said.

In addition, TMA’s renovated headquarters will see the archive move to a newly central spot on the penthouse floor.

Dr. Steffensen emphasizes the importance of maintaining a physical archive, where physicians and others can discover history anew and come across artifacts by chance – not only by direct searches of an online database.

“Discovery is possible in an archive,” he said.

Despite his passion for history, Dr. Steffensen is clear-eyed about the challenges of historical preservation. It’s hard to know in advance which past events – like the 1918 pandemic – will become relevant in the future. It also takes serious manpower to sort through every archived item, some of which are handwritten or saved in outdated formats, like VHS tapes.

But he lands on the side of caution.

“There are millions of stories waiting to be told in the archives,” he said. “Unless we preserve that history, some of those stories will never be told.”

Dr. Joseph agrees. His own interest in medical history centers on his specialty – obstetrics and gynecology – and its evolving norms, such as the use of forceps during deliveries. An archive ensures future physicians can learn about past norms and tools.

“I consider it very much like a museum that preserves the best of art,” he said.

His co-editor, Dr. Green, encourages fellow physicians to pay a visit to the archive – either in its physical or digital form – and to share their favorite finds with others. Without such awareness and activity, the archive could languish.

“TMA has recognized that we need a place to go to learn what our forebears were putting up with,” he said. The renovated and digitized archives “are all giving access to our past in ways that never existed before.”