In 2014, a man entered a Dallas hospital complaining of a headache, abdominal pain, and a low-grade fever. The emergency department physician sent him home with some antibiotics after concluding he had sinusitis. It turned out to be one of the best-known misdiagnoses in recent history.

Two days later, the man returned to the same hospital with much more severe symptoms, and his illness – which turned out to be fatal – was quickly identified as Ebola. It was a missed opportunity in timely care because the patient was not asked about his travel history and had just returned from Liberia, then an Ebola-epidemic country.

That incident points out the importance of getting a thorough travel history from a patient – especially during heavy travel seasons. While the Ebola case is well known, physicians can also miss important diagnoses for diseases such as malaria and measles if they don’t pursue travel questions, says Lubbock infectious disease specialist Scott Milton, MD, a member of the Texas Medical Assocation’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and Region I medical director for the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS).

“I remember seeing my neighbor 15 years ago who was sick with a fever, and she asked me to come by and look at her,” he said. “About 10 minutes into the conversation she casually mentioned that she had just got back from Costa Rica. She ended up having dengue.”

Missing travel-related information can harm the patient – as in the case of dengue or malaria – and lead to wider public health concerns when an infectious disease is involved, such as Ebola, says Susan McLellan, MD, a member of the Committee on Infectious Diseases who teaches at UTMB John Sealy School of Medicine in Galveston.

“Not only cases of significant diseases that are a risk for the patient have been missed, but also cases that represent a significant risk to the community have been missed because physicians didn’t think that travel history was that important or were [too casual] in collecting that travel history,” she said.

Travel questions are gaining importance because international travel has picked up, and so too has the spread of travel-related infectious diseases and physicians’ responsibility to more thoroughly investigate patients’ travel plans and history during visits.

As many as 43% to 79% of travelers to low- and middle-income countries become ill with a travel-associated health problem, according to the 2024 edition of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Yellow Book, which provides international travelers and clinicians with expert guidance for safe and healthy travel abroad (tma.tips/CDCTravel).

In 2024 alone, CDC issued multiple health advisories related, for instance, to a new surge of Oropouche, human parvovirus, dengue, and meningococcal disease, among other infectious diseases.

Physicians typically are trained in medical school to ask questions like “Where have you traveled to lately?” as part of their routine screening, Dr. McLellan said. But physicians who are not following up on that question aggressively should consider expanding their list of questions to gain a deeper knowledge about where patients have visited.

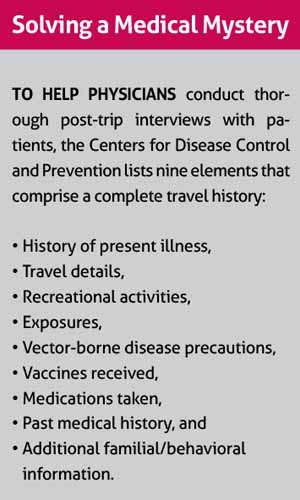

CDC advises physicians to ask questions about travel details, recreational activities, vaccinations received, and past medical history, along with others to help diagnose a travel-related illness. (See “Solving a Medical Mystery,” page 44.)

“It’s very important to ask [about a patient’s travel history] and to ask very specific things,” she said. “What was your mode of travel? Were you going to high-end hotels for a conference, or were you backpacking and staying with locals and eating whatever food came your way?”

Other specific questions might include asking patients were they around animals, did they provide medical care, were they near any sick relatives, or did they attend funerals, Dr. McLellan says. Physicians suspecting some diseases – like mpox – should ask about sexual activity as well.

“All of those things can give you a clue that there can be something more than [identifying] viral syndrome and sending them home,” she said.

Obviously, some specialties are more affected by travel than others – family physicians, pediatricians, and emergency room physicians, and of course, infectious disease physicians, Dr. Milton says.

“For an orthopedist doing a hip replacement, it’s probably not quite as important,” he said.

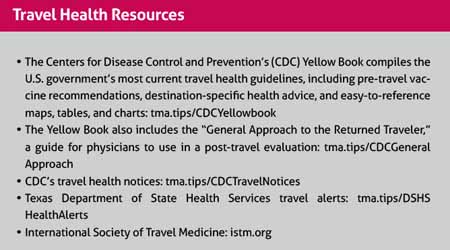

Physicians who are the first point of contact for a patient with a travel-related illness frequently have little training about diseases not endemic to their own region, and what they hear in the news may be confusing, Dr. McLellan says. That is why keeping up with disease alerts from CDC, DSHS, and local health authorities is vital. (See “Travel Health Resources,” page 43.)

Awareness about the risk of exposure to a disease from a distant locale may be key when people present with nonspecific symptoms such as a fever, rash, or respiratory complaints.

Physicians become skilled at questioning patients over time, Dr. McLellan adds. But it’s important to not let assumptions get in the way of completeness. For instance, physicians should remember that exotic diseases can be acquired in wealthy and poor countries alike.

“If you go to Germany and go hiking in the Black Forest, you can get tick-borne encephalitis, which is something people might not otherwise think about,” she said. “Travelers might not think to mention their trip to Europe.”

Also, travelers can stay in Texas or the U.S. and still pick up a nasty bug.

“There are certain diseases that are endemic to the western deserts and some that are endemic to the Mississippi River or Ohio River valley that can affect individuals,” she said. “We have murine typhus, which is now endemic to South Texas and is spreading. It has a nonspecific fever and unless you suspect it, you’re not going to be able to tell it from any one of a number of things.”

As the world evolves, physicians can expect to see more cases of diseases that are not endemic to the U.S., Dr. Milton says. Knowing what is endemic or where an outbreak has occurred in a visited area can help physicians rule out certain infections and choose an appropriate diagnostic test through the process of elimination.

“There’s a long [data table I showed medical students] of all the potential causes of fever for people who have [returned] from an area that’s endemic for malaria,” he said. “At the top of the table, 25% of the time, it’s malaria. So you’d better ask about any potential malaria risks or exposures and bring in more complicated questions, like where were you and were you trying to protect yourself from malaria.”

But the bottom of that data table showed that 25% of the time, physicians never found out the source of a nonspecific fever for those patients, Dr. Milton says.

“You may never figure it out,” he said. “You can test them up and down, and they get sick, and they get better, and you never get a diagnosis.”

One of the best ways for patients to avoid post-trip illnesses is for physicians to help them plan ahead before their trips by getting the recommended counseling, vaccinations, and medicines for the region they’re visiting, Dr. Milton says.

CDC’s website on traveler health spells out steps patients can take before visiting a country (tma.tips/CDCTravelers). The public health agency also posts travel health notices in four tiers of severity, from Level 1 advising normal precautions to Level 4 advising total avoidance of travel.

Physicians can suggest precautions such as practicing good hygiene and mosquito-bite prevention. Also, pregnant women need to understand that visiting a country where some diseases – like Oropouche – are endemic can pose a serious threat to a baby.

“Too often physicians don’t ask those kinds of questions, especially ‘Are you traveling?’ and ‘Where are you traveling?’” Dr. Milton said. “Many times, it’s important to get vaccinated several weeks before you leave. So, there’s some planning that should go into that.”

Patients can also visit a specialist in travel medicine who can counsel them about how to prepare for their trip, Dr. McLellan says.

“Any travel medicine provider can help you understand what the specific risks are for the type of travel you’re doing,” she said.