Mark Casanova, MD, has a sign in his office reminding him of his team’s unconventional motto: “Stomp Out Suffering.”

“A number of years ago, at the end of a team meeting, I just uttered the words as motivation,” the Dallas-based palliative care specialist with Baylor Scott & White said of its origins. “I said, ‘OK, let’s all go jump into the trenches and stomp out suffering.’ And it just stuck. It’s just this unceasing desire to address suffering in all of its forms. You’ve got to address the psychological, spiritual, emotional, and physical. If you just address one piece of it, you’re missing it.”

The Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 11 in a 2017 special session. The legislation provided a framework that regulates in-facility do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. It went into effect on April 1, 2018, and impacted how he and other colleagues dealt with one of the most important ways to address a patient’s suffering: principled and mindful end-of-life care. Previously, only out-of-hospital DNR orders were explicitly regulated in the Texas Advance Directives Act (TADA).

Presenting at the Texas Medical Association’s 2019 Winter Conference, Austin attorney Missy Atwood likened SB 11 to a “Rubik’s Cube,” noting the new law detailed “nine options for putting a valid [in-facility DNR order] in place.” For years, the law generated enough confusion and fear that TMA leaders knew they had to act, culminating in a multistakeholder discussion of needed changes to TADA nine months before the start of the 2023 legislature session. Those negotiations eventually led to the passage of House Bill 3162.

Working with those stakeholders – including the Texas Hospital Association, Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, Coalition for Texans with Disabilities, Texas Alliance for Life, and Texas Right to Life – TMA representatives spent countless hours negotiating the legislation, which includes significant changes in the law in areas of in-facility DNRs and the ethics or medical committee review process.

“There’s this old adage that if everybody’s unhappy about something about a bill, then that tells you it’s a good bill,” Dr. Casanova said of the negotiations. “It was a good compromise.”

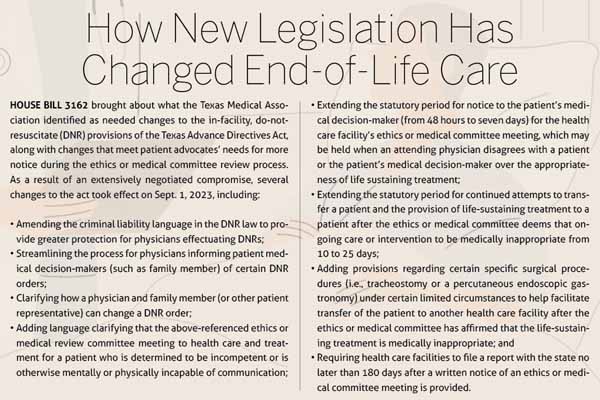

The new law, which took effect Sept. 1, 2023, provides some welcome changes for physicians, such as improvements to the DNR provisions concerning who may issue a DNR order (in certain circumstances changing it from attending physician to a physician providing direct care to the patient), and to DNR provisions concerning potential criminal liability. It also incorporates multiple other stakeholders’ ideas for amending TADA, including giving families more time to consider end-of-life care for their loved ones while maintaining physicians’ ability to exercise their medical judgment in delivering appropriate care. (See “How New Legislation Has Changed End-of-Life Care,” page 19.)

Anecdotally, HB 3162 appears to be improving communication between physicians and patient families. Since it went into effect, Baylor Scott & White hasn’t had a single ethics or medical review committee life-sustaining treatment case in its entire system that’s progressed to the stage at which family is notified of an ethics committee hearing, according to Dr. Casanova and his colleague Robert Fine, MD, director of Baylor Scott & White’s Office of Clinical Ethics and Palliative Care. Both physicians expect statewide numbers to be extremely low.

Six years ago, Dr. Casanova’s mom passed away, and he experienced the end-of-life care process from a family member’s point of view rather than his usual role as a care facilitator.

“It’s a very strange, almost surreal experience to be sitting there as a family member and then having a doctor and a social worker come in and say, ‘We’re with the palliative care team.’ And I thought to myself, ‘Oh, this is what this feels like,’” he said. “But it was a supportive experience. And I think that’s the key. By the time you get to dispute resolution process, as the name implies, there’s a dispute. We really want to do all that we can to not get there in the first place.”

Involving physicians

End-of-life care “has always been challenging, even more so with each passing year of technologic advancement,” observed Dr. Fine, who has been involved with end-of-life care legislation in Texas since 1998. He initially participated in discussions leading to TADA’s creation and has been involved since in what he terms “fighting our best” to advocate for Texas physicians and medically appropriate care.

“From a patient perspective, we all want to live, but we’ve all got to die,” Dr. Fine said. “Patients tend to accept that latter reality better than families do. From a physician perspective, we want to help the patient live as long and as well as possible, but when death becomes inevitable, we want to help the patient die gently.”

TMA Director of Public Affairs Matt Dowling says the association was instrumental in securing portions of HB 3162 that safeguard physicians’ medical decision-making and allow them to use their judgment in end-of-life decisions.

“We needed to figure out a way to create a compromise that works for our physicians and also works for other stakeholders — and we were able to do that,” Mr. Dowling said.

TMA gathered an initial group of stakeholders, sending an April 2022 letter signed by all those groups to key Texas senators and representatives who either filed or co-sponsored bills to reform portions of TADA or chaired relevant House and Senate committees.

Four months later, Rep. Stephanie Klick (R-Fort Worth) convened the stakeholders who signed the original letter, plus Texas Right to Life and Protect TX Fragile Kids, for a dozen meetings, lasting between three and five hours each, to shape what eventually became HB 3162.

Dispute resolution

Patient advocate groups in the negotiations sought changes to the ethics or medical committee review process that health care facilities use when a physician disagrees with a patient or the patient’s medical decision-maker regarding the appropriateness of life sustaining treatment.

HB 3162 brought several changes to the ethics or medical review committee process that a health care facility uses in these circumstances.

First, the notification period to let family members know the ethics or medical committee is meeting was extended from 48 hours to seven days.

Next, the law was amended to clarify that the ethics or medical committee review process only applies to health care and treatment for a patient who is determined to be incompetent or is otherwise mentally or physically incapable of communication.

Previously, following the ethics committee meeting, should it side with a physician by determining that life-sustaining treatment is medically inappropriate, the physician would notify the family and then wait 10 days before withdrawing that care or intervention.

The new law extended that 10-day period to 25 days. Additionally, under the new law, should the patient’s family wish to transfer the patient to a different health care facility in order to continue life-sustaining treatment, the attending physician or another physician responsible for the care of the patient is required to carry out certain specific procedures to facilitate the transfer but only if several prerequisite conditions are also satisfied.

Dr. Fine noted that those three phases of the dispute resolution process – notifying family members it will take place, the ethics or medical committee meeting, and the notification period for ending medically inappropriate care – extends the whole process from about 14 days under the former law to 35 days with HB 3162’s extended time parameters.

His concern with these changes is that these types of reviews, as rare as they are, potentially prolong the life of a patient who may be ready to die, or who might even die before the now-extended process runs its course.

Yet, Dr. Casanova notes that the two-time extensions written into HB 3162 represent a compromise from the indefinite “treat to transfer” language that could have been written into the bill without physician input.

Mr. Dowling adds that another challenging item in the negotiations involved adding language about performing a tracheostomy or a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy on a patient when, in the attending physician’s judgment, the medical procedure is reasonable and necessary to effect the transfer of the patient from one medical facility to another (and meets certain other prerequisite conditions). While TMA was concerned that specific procedures would be included by name in a statute, rather than leaving all procedure decisions to a physician’s judgment and knowledge, the compromise written into the bill still gives physicians the agency to decide whether that procedure is medically inappropriate.

On issues like disability protections, under which patient advocates wanted to make sure ethics or medical committees weren’t making quality-of-life judgments in their reviews, TMA and other stakeholders were able to reach an agreement on clarifying language.

Impacting practice

By being in the negotiations to the end and advocating for physicians throughout, Dr. Casanova was able to bring his “stomp out suffering” perspective to the discussions.

He notes that the ethics or medical committee review negotiations also created more awareness of the need for better communication, potentially resulting in fewer disputes between physicians and family members over a loved one’s DNR status. He’s already seen changes leading to less angst for physicians and better communication with patients as well.

Thanks to HB 3162, cases involving potential criminal liability for a physician when taking certain actions regarding a DNR order (including effectuating the order) now must show a specific intent to violate the law, which Dr. Casanova believes will improve the anxiety that SB 11 from the first called session in 2017 produced for some health care professionals.

“When we passed the bill, we did a lot of education, and I used to get more frequent calls of angst and nervousness, of ‘Which form do I use?’ or ‘Which number in the form do I use?’ I think physicians in general understand the temperature has been dialed down with this,” Dr. Casanova said.

Although language about criminal liability wasn’t entirely scrubbed from SB 11’s changes to TADA, Dr. Fine agrees the higher standard is “one of the small victories we can take from this.”

Both doctors also brought perspective on resuscitation shaped by their palliative care work.

“CPR was invented for unexpected death. For sudden cardiac arrest, if it’s the first evidence that you have heart disease, CPR is a wonderful thing,” Dr. Fine said. “When somebody’s dying from stage four metastatic cancer, to subject them to CPR – which some families insist upon – is just cruel. It’s not changing the cancer.

“I know doctors struggle about this. We get lots of calls from doctors who are just facing moral distress. They’re going, ‘I’m torturing my patient. I don’t want to do this to them, but the family insists. What else can I do?’”

Dr. Casanova makes a distinction between his preferred term, do not attempt resuscitation, and the do-not-resuscitate nomenclature referenced in state law.

He points out resuscitate is problematic compared to attempted resuscitation.

“There’s an implicit inference that it actually works abundantly well,” he said of the former. “And it just doesn’t in certain settings.”

As for the ethics or medical committee review process, Dr. Casanova’s discussions with physicians indicate the extended time period the law calls for makes them more wary to enter that process. Physicians are constantly striving, however, to seek better communication with patient surrogates to resolve conflicts before they get to the dispute resolution stage.

“During the negotiations, as we were talking about various scenarios, some of them were real-life stories,” he said. “And then, myself or Dr. Fine or some of the other physicians would share, ‘Well, this is what we would have said. This is how we would have handled it.’

“The response is, not infrequently, something along the lines of ‘Had they said that, we would have chosen differently,’ or ‘The way that you said it makes perfect sense, and I don’t think this family would have had issue with that. I think there would have been closure. There would have been peace.’ It just goes to show that sometimes it all boils down to the effectiveness of communication.”

HB 3162 brings a welcome change in how physicians communicate with patient decision-makers regarding certain required notices of in-facility DNR status. Previously, in certain circumstances a physician was legally obligated to notify patient medical decision-makers of their loved one’s DNR status multiple times – potentially distressing for some families. With the change, a single notification now suffices.

Dr. Fine also pointed out that one tool still at physicians’ disposal under Texas law is that they can’t withhold medication necessary for comfort, such as morphine. So, even when a physician believes life-sustaining care is medically inappropriate, that physician can still help lessen whatever suffering a patient might be experiencing.

A compromise worked out with patient advocates allows a DNR to be issued by the patient’s attending physician for a patient who is incompetent or otherwise mentally or physically incapable of communication if both the physician and surrogate agree to it (and it is concurred in by another physician meeting certain requirements).

If a patient expressed a wish for CPR during a hospitalization and didn’t change it, even though that patient’s condition might have taken a catastrophic turn, a physician still can’t unilaterally write a DNR order overriding the patient’s prior wishes.

A way that can change, according to Dr. Casanova, is by what he terms the “triangulation pathway,” in which a family member or other surrogate expresses a desire to change the patient’s status to DNR, the attending physician agrees, and then it is concurred in by another physician who is not involved in the direct treatment of the patient or who is a representative of an ethics or medical committee of the health facility in which the person is a patient.

Dr. Casanova observed that while dispute resolution typically affects ICU patients, impacting those ICU physicians and ethics consultants most, code status discussions affect every physician that works in a hospital.

He adds that thanks to HB 3162, physicians can more confidently make code status decisions, including when patients have articulated wishes, prior to becoming unconscious or otherwise incapacitated, that family members then want to step in and change. That victory, combined with the improved criminal liability language regarding in-facility DNRs, were crucial to Dr. Casanova in the negotiations.

“That was where a good portion of our focus was,” he said. “Can we mitigate some of the potential legal threats to physicians, the criminal liability? Can we make it such that a person’s expressed desires actually stick, and not a situation where they lose consciousness or lose capacity to make their own decisions, and then a surrogate, a family member, is able to override those pretty sacred expressions of desire for their end of life, right? Looking at everything in totality, it was, in fact, a positive outcome for the House of Medicine.”