Austin pediatrician Sandra Frasser, MD, learned early in her medical career that many of the biggest health problems patients face cannot be fixed by a trip to the doctor’s office.

“I had a 1-month-old with a terrible rash all over her body, and it was because the family was having to live with their windows open during the month of August’s 100-degree weather because the landlord wouldn’t fix the air conditioner, even after repeated requests by the parents,” she said. “So this 1-month-old was getting bit up [by mosquitoes].”

For many families, just one nonmedical problem – like a broken air conditioner – can set off a chain reaction of health crises, says David Lakey, MD, vice chancellor for health affairs and chief medical officer at The University of Texas System.

In this case, the physical and mental stress of living with mosquito bites in a sweltering house might cause other health problems for the baby. That, in turn, might trigger greater difficulty for the parents because of lack of sleep and the constant care demanded from an unhappy baby.

“All those things in [a patient’s] environment can have a profound effect on whether they can live a healthy life or not,” said Dr. Lakey, a former commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS).

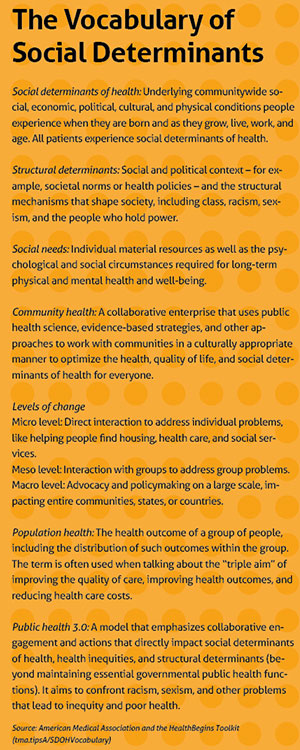

Taken together, those environmental and socioeconomic forces are known as social determinants (or drivers) of health. They span a range of societal issues, including food access, housing, transportation, education, income level, ability to exercise, family upbringing, and education. (See “The Vocabulary of Social Determinants,” page 19.)

Taken together, those environmental and socioeconomic forces are known as social determinants (or drivers) of health. They span a range of societal issues, including food access, housing, transportation, education, income level, ability to exercise, family upbringing, and education. (See “The Vocabulary of Social Determinants,” page 19.)

Many families with a broken air conditioner would just have to live with it – and the health problems it causes, Dr. Frasser says.

“When I started working with [low-income] patients in medical school and residency, it showed me there was only so much I could do to help them with their medical concerns when they had so many societal factors affecting their health,” Dr. Frasser said.

But now that People’s Community Clinic, where Dr. Frasser works, is part of a medical-legal partnership, she was able to refer the case to a lawyer with experience in housing issues. The lawyer working with People’s got in touch with the family’s landlord “and they got it fixed right away,” she said.

Physicians’ awareness of social determinants of health has increased since the term was first coined in the 1970s, but it has taken a long time, says Tyler pediatrician Valerie Smith, MD.

“When I went to medical school 20 years ago, I don’t recall ever hearing that term, even though that terminology did exist,” Dr. Smith said. “And certainly, it was not a part of how I was taught to consider or treat patients.”

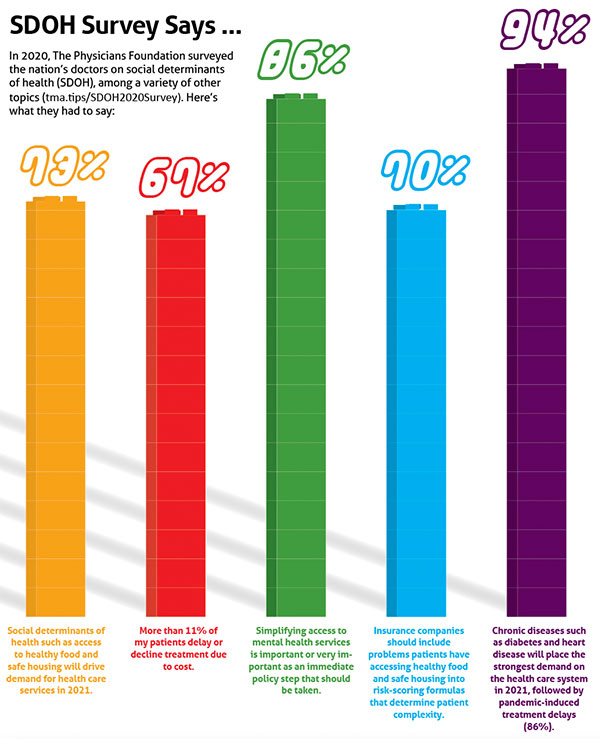

Today, most medical schools teach about social determinants of health. And a 2020 survey of U.S. physicians found that 73% of physicians indicate that social determinants of health, such as access to healthy food and safe housing, will drive demand for health care services in 2021, according to The Physicians Foundation, which is supported in part by the Texas Medical Association. (See “SDOH Survey Says ...,” page 20.)

But interest in social determinants among physicians is often based on work experience, Dr. Smith says. Those who work at academic medical centers or who – like her – work with patients on Medicaid are usually on the lookout for problems caused by nonmedical factors, she says. However, physicians who treat patients with mostly private health insurance may be less concerned with social determinants because they assume their patients’ income or education level insulates them.

Nevertheless, research shows everyone is affected by social determinants of health. Up to 80% of the factors that influence health take place outside an exam room, according to the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

Even families with means go through crises like job loss or divorce that can affect their health, Dr. Smith says.

“While it might not be a majority of your patients, you can’t go a day interacting with families in East Texas and not have interacted with a family that’s dealing with food insecurity,” she said.

Screen sharing

The first step to addressing social determinants of health is for physicians or someone on their team to screen patients for them, says Eduardo Sanchez, MD, chief medical officer for prevention and chief of the Center for Health Metrics and Evaluation for the American Heart Association in Dallas. (See “Creative Collaboration,” page 24.)

Talking about social determinants of health can bring up sensitive subjects about people’s background, including adverse childhood experiences or low educational attainment, he says. Yet these factors correlate with tobacco use and substance use.

“It’s just like when you use a screening tool or test to diagnose a medical condition,” said Dr. Sanchez, a former DSHS commissioner. “The diagnosis and the plan to address the problem can be enhanced by understanding some of the social needs, i.e., social determinants, that can get in the way, or may have already gotten in the way of making this person as healthy as they could be. This is not about ascribing fault as much as it is identifying factors that should be considered or addressed.”

Physicians sometimes hesitate to screen for social determinants because they assume there’s nothing they can do to help directly, or they have inadequate local resources to refer patients to, says Vincent Fonseca, MD, a public health and general preventive medicine specialist in San Antonio.

“If physicians don’t know how to assist, or lack confidence that they can effectively assist patients with health-related social needs, then the issue goes into the too-hard-to-do pile that goes unaddressed,” he said.

Spurred by the shift to value-based care, health systems nationwide have incorporated screening tools for social determinants into primary care and other clinical settings, according to a survey by Deloitte, a professional services company. (See “Obstacles to Clear,” page 30.)

For instance, most electronic health records (EHRs) now feature tools to screen and address social determinants of health, Dr. Fonseca says. However, the most effective ones are custom add-ons, not standard features.

Typically, physician practices are not equipped to help patients directly with social determinants, but that is changing.

At People’s Community Clinic, Dr. Frasser works with attorneys through the medical-legal partnership, social workers who counsel patients, and community health workers who help patients find and navigate resources. This includes connecting them to community-based organizations, filling out forms for assistance, or checking with government agencies that offer specialized benefit programs.

“And then [the community health workers] circle back and ask, ‘Did you get that need met? If not, how can I help you?’” Dr. Frasser said.

Dr. Smith’s practice, St. Paul Children’s Services in Tyler, is part of a food pantry, allowing her to prescribe healthy food for patients with food insecurity and other food-related problems, she says.

Most medical practices cannot afford a direct professional connection with lawyers, social workers, food banks and pantries, and similar resources, Dr. Fonseca acknowledges.

However, physicians and their staffs should become familiar with similar resources in their region, he says. They can approach local law firms about providing pro-bono or low-cost legal services; find social workers who can help patients with counseling and guidance in obtaining services; and identify where the nearest food bank or food pantry is to help patients with food insecurity.

“Really, it’s developing the awareness of how do I meet a patient’s social needs … to connect with services in the community,” he said. “Somebody in the community has something going on [and can help].”

There are already services that help with this effort. AuntBertha.com or calling 2-1-1 in some areas can help patients and physician offices locate the resources nearest to them, Dr. Fonseca says.

But these services have limits, he says. The contact information they provide may be just a general phone number, meaning either patients or physician offices must spend time tracking down the people who can help with their specific situation.

“It’s often too hard to do, and people don’t do it,” Dr. Fonseca said.

That kind of discouragement happens frequently when patients are referred to services, says Brandon Altillo, MD, an assistant professor in the departments of population health, internal medicine, and pediatrics at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. His research also shows many patients just get busy and fail to follow up.

“Part of our work with that is working with United Way and other organizations around town to make those referrals bidirectional,” he said. “So, when we refer someone to a social service provider, the social service provider can follow up with us and send us a report – just as you would with a medical referral – to say, ‘We did see this patient,’ and sort of close the loop.”

Resource management

Some topics are more difficult to screen for than others. For instance, the screen Dr. Altillo uses does not mention race – a key social determinant – so he frequently follows up on the subject in the exam room. He’s found many Black men are afraid of exercising in their neighborhood, in part because of news stories about police abuse of Black people and because of a high-profile attack by three white men on a Black jogger in Georgia in February 2020.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had Black patients who tell me that they can’t exercise because they’re afraid of being shot outside,” he said.

For some social determinants of health, the resources available don’t adequately address the problem, Dr. Fonseca says. That is especially true with transportation.

Texas’ car-based culture makes it difficult for low-income people to get around if their car breaks down or they cannot afford to own one. Most large cities have mass transit, but in Texas mass transit often is unreliable, he says. That makes it difficult for patients to get to and from medical appointments or to pick up prescriptions, he says.

“In San Antonio, where we have buses … patients will tell us flat out, ‘It’s only five miles [to the appointment], but it’s two bus connections, and I’m not going to do that. It will take me four hours,’” Dr. Fonseca said.

The task of tackling social determinants of health is not up to physicians alone, Dr. Sanchez says. It will require physicians to educate lawmakers and policymakers at all levels of government about the impact of social determinants of health. (See “Going Local,” page 34.)

“Physicians ought to be [working] through organizations like TMA to do the advocacy that needs to be done,” he said. “For example, to assure that more people have access to affordable and adequate health insurance. Or that food security is being addressed at a societal level beyond the individual level.”

Focus groups conducted by The Physicians Foundation show addressing social determinants has popular appeal, says foundation CEO Robert Seligson.

“Most people, regardless of where they end up on the political spectrum, if you can tell them that by investing in social determinants of health that it improves outcomes and saves money, they’re more apt to want to use taxpayer money,” he said.

The data physicians collect in screening patients for social determinants of health can be used to help make the case that decisionmakers should act on behalf of those same patients, Dr. Altillo says.

“If we have data that say a lot of people are struggling with housing, we can go to the city council and say that we really need to improve our funding for the housing authority because these waits of over a year for housing are just not tenable,” he said.

Physicians who take part in local health initiatives like school health advisory councils (SHACs) also can help shape local attitudes on social determinants, Dr. Lakey says. SHACs are volunteer advisory panels that ensure each school district’s health programs reflect local community values. (See “Join Your Local SHAC,” page 21.)

But perhaps the best way is to speak up regularly about the need for more local resources and services that address social determinants of health, he says.

“The physician can be a strong voice and a leader in their community,” Dr. Lakey said. “Let people know how important it is to have these types of programs and services.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(9):16-23

September 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page