This story is in no way affiliated with the EHR vendor NextGen Healthcare. Any similarity is purely coincidental.

Waco family physician Stefan Huber, DO, has grand plans to open his own private practice in the near future.

As a millennial – defined as one born between 1981 and 1996, and now between the ages of 26 and 41 – the third-year resident at the Waco Family Medicine Institute envisions a practice that caters to this generation of patients and health care professionals, without eschewing other demographics; a new kind of doctor’s office that blends a traditional private practice with an urgent care center, offering expanded hours and more integrated technology.

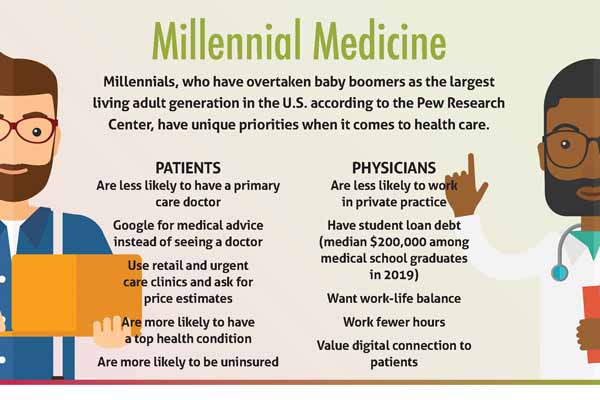

Millennials overtook baby boomers as the largest living adult generation in the U.S. in 2019, according to the Pew Research Center. (See “Generations Defined,” page 17.)

As patients in search of on-demand care and transparent pricing, they’re providing the impetus for new practice models and for existing practices to adapt. As physicians, they’re carving out more supportive, sustainable workplaces.

These trends have informed some of Dr. Huber’s guiding principles.

To appeal to millennial patients, Dr. Huber says he’ll offer online scheduling, walk-in appointments, and longer hours, providing the instant gratification that consumers find in other sectors – through Amazon, Uber, and H-E-B curbside pickup – alongside a lasting patient-physician relationship.

To maintain his own work-life balance, and that of his staff, Dr. Huber plans to use an iPad-enabled smart dictation device, which he says will cut down on time spent updating patients’ electronic health records (EHRs). Similarly, he wants to lean into telemedicine and the use of smart medical devices to monitor patients’ vitals at home, both of which have grown more popular during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s just … a new day and age,” he said. “If you’re not seeing this practice of the future and where the market’s looking like [it’s headed], it’s going to pass you up a little bit.”

Dr. Huber’s vision remains untested, for now. But physicians like Juliet Breeze, MD, have proven its merit. Over the past decade, the Houston family physician has grown Next Level Urgent Care to multiple locations across Texas largely powered by one demographic: 15- to 43-year-olds in search of affordable, on-demand health care.

“Older generations are very used to the concept of, ‘You have one doctor. And you wait for that doctor to be available. And you conform to that doctor’s schedule,’” she said. “The younger generations are really growing up in a convenience culture where they can wake up in the middle of the night and realize they need some toilet paper … and have it delivered the next day on an Amazon truck.”

With less stable employment and higher uninsurance rates than previous generations, millennial patients are less likely to have a primary care physician and more likely to seek out retail clinics and urgent care centers.

But traditional primary care practices are hardly obsolete and can adapt just as they did during the pandemic, even as competition grows with the likes of retail medicine, says Plano family physician Christopher Crow, MD. The GenX-er (now ages 42 to 57) says millennials’ attitudes are changing as they become caregivers themselves and age into chronic illnesses.

“We’re seeing a transition where [millennials] realize that they’re needing a primary care relationship,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a retail clinic that’s going to be able to help you … quarterback your health over multiple decades. You’re going to have to have an ongoing [primary care] relationship to age well or optimally.”

These physicians are among a growing number drawing from a similar playbook – implement technology, offer flexible schedules, and engage with a public that is increasingly online – to recruit the next generation of patients and health care professionals.

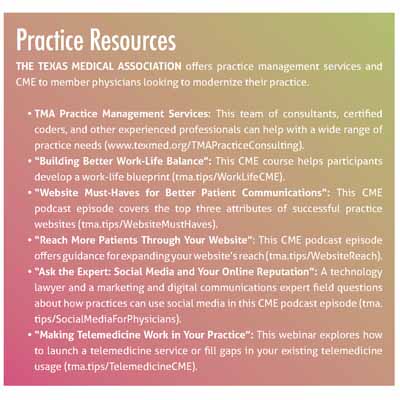

The Texas Medical Association can help practices make this shift and continues to lobby at the state and federal levels to bolster telemedicine coverage, reduce onerous administrative burdens that tie up physicians’ time, and expand the physician workforce. (See “Practice Resources,” page 19.) TMA’s Young Physician Section, which represents members who are in their first eight years of practice, also provides support to those making the transition from medical resident to full-fledged, practicing doctor.

But these changes don’t have to come at the cost of existing patients.

Dr. Huber says millennials are used to navigating different worlds: the analog one of their parents and grandparents and the online one of Generation Z digital natives. He aims to strike a balance in his own practice, catering to millennial patients and staff while still maintaining traditional amenities – like accepting appointments over the phone from those who don’t want to fuss with an app.

“We will not shun anyone,” he said. “We will welcome all.”

A gap in the market

Dr. Breeze, also a Gen X-er, hatched her business plan after her young son injured himself one weekend. The injury wasn’t life-threatening, but she didn’t want to wait until the following week to take him to his pediatrician. So, they went to a freestanding emergency department, where she says they had an excellent experience – until the “exorbitant” bill arrived.

Urgent care offered an alternative. But Dr. Breeze says traditional health care generally has been slow to provide such options. For instance, primary care practices rarely offer same-day appointments and sometimes have weeks-long waits for new patients. Many also operate on a fee-for-service basis, she adds, and struggle to answer patients’ billing questions.

Meanwhile, their competitors – including urgent care centers, freestanding emergency departments, concierge medicine, and retail clinics like Walmart Health and CVS MinuteClinics – have responded to patient demands for convenience and price transparency. And this threat looms large on the horizon. As this article was being written, Amazon and CVS were competing to acquire One Medical, a concierge primary care company with nine locations in Texas.

Dr. Breeze attributes urgent care’s appeal, in part, to anticipating these market trends. In addition to offering longer hours and walk-in appointments, Next Level negotiates capitated, or flat, rates with insurers, which allows it to provide patients with upfront cost estimates for urgent care.

“It [can be] impossible for patients to get a price prior to receiving care, which makes it extremely frustrating – and sometimes scary – for people to get [that] care,” she added.

The business also has expanded into value-based advanced primary care, contracting with employers with self-funded health plans that offer no-cost primary and urgent care to enrolled employees and their dependents.

This model appeals to employers, like the Houston school district, that want to reduce their health care spending and that need to compete for candidates in a tight labor market. It also helps foster a healthy workplace.

“What I love about value-based care and … providing no-cost care to patients is it takes a lot of stress out of the workplace for the physician and our staff when they don’t have to talk people into tests [or other services] that cost extra money,” Dr. Breeze said. Patients tend to comply at higher rates because they aren’t worried about whether they can afford to do so, she adds.

But how does a practice balance convenience and transparency for patients with flexible scheduling for their physicians and staff? Dr. Breeze says these priorities work in tandem.

By offering longer hours, these practice models also can offer shift work to their employees, who may find it more flexible than fixed office hours. By negotiating with insurance companies to offer case rates and with employers to offer no-cost health plans, they minimize the administrative burden on staff, including chasing down prior authorizations and unpaid invoices, and maximize the time physicians spend with patients.

“We are trying to provide what a millennial workforce might want, which is less isolation [and] more convenience,” she said.

Adapting the traditional practice

Dr. Crow, the Plano family physician, agrees that millennial patients want more convenience than previous generations. And he admits that primary care practices face competition from urgent care centers and retail clinics, which, he said, “have benefited from those millennial preferences more than anybody.”

But this may be changing.

As co-founder and CEO of Catalyst Health Group, a large clinically integrated primary care network, Dr. Crow has noticed a shift in millennials’ attitudes.

As they become parents themselves and take on caregiving responsibilities for aging parents, he says they’re seeing the value of primary care relationships – such as with their children’s pediatrician – and wanting to stay healthy for their family.

They’re also contending with health concerns that warrant a lasting relationship.

“In the last decade or so, with technology and productivity hacks around delivery, and social media keeping people on their phones more and less active, and the rise of more and more fast food, you’ve got a generation that actually has more chronic disease at their age than prior generations,” he said.

A 2019 study of medical claims by Blue Cross Blue Shield Health Index found millennials were substantially more likely to be diagnosed with eight of the top 10 health conditions than Generation X before them.

Conditions like attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, diabetes, and depression may prompt millennials to seek out a primary care physician, if they haven’t already.

At the same time, he notes, primary care practices are evolving to meet millennial patients’ needs, such as by offering more flexible appointment times and online scheduling.

“The technology’s improving around [EHRs], and physicians are getting more comfortable with telehealth because of COVID,” he said. “Also, you have millennial physicians now, who have the same attributes and values [as millennial patients] and are driving those changes within organizations.”

Medicine’s rising ranks

Millennial physicians say they, too, want benefits like more flexible schedules, work-life balance, digital connection to patients, and collaboration with colleagues. Nearly three years into the COVID-19 pandemic and amid worsening workforce shortages across the health care industry, some employers are delivering on these demands.

Gates Colbert, MD, a nephrologist in Dallas and chair of TMA’s Young Physician Section, sought out a private practice affiliated with a university medical center when he was starting his career. This hybrid role affords him independence and the opportunity to teach medical students, residents, and fellows.

Dr. Colbert says he sees many young physicians opt for employed positions for similar reasons: flexibility and work-life balance.

“Young physicians want shift work,” he said. “They want to have a time when they’re on and a time when they’re off.”

Many medical students, residents, and young physicians also are open to career paths outside of medicine. A 2017 survey by the American Medical Association and M3 Global Research found nearly four out of five millennial physicians said they eventually hoped to pursue other fields, including entrepreneurship, health care consulting, health system administration, and academic research.

Dr. Colbert has seen this finding bear out in his role as an assistant clinical professor at Texas A&M University School of Medicine in Dallas.

“Right now, we’re in the side-gig economy,” he said. “Some of that is rooted in [how] society has changed. The physician is not this ultimate leader, and the respect for physicians has dwindled a little bit over time. One result is that young physicians don’t always see their clinical job as their only possible career path.”

Plano critical care anesthesiologist Joy Lo Chen, MD, acknowledges these trends may seem anathema to older physicians, for whom the prevailing attitude was often one of self-sacrifice.

“The environment now is a lot more wellness-friendly, whereas before my time it was a lot more, ‘You stay until you get the work done, and you don’t really put yourself before the work,’” she said.

For instance, Dr. Chen, an associate professor in anesthesiology and pain management at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, cites a recent, successful effort by residents to secure protected lecture times. She also asked a colleague and their boss to cover for her at the beginning of a 12-hour shift for a family event in August.

“My boss cares about me being able to take my daughter to her first day of kindergarten,” she said.

Although millennial physicians tend to prioritize work-life balance more than their older colleagues, Dr. Colbert says they are much more “digitally available,” through health care apps and patient portals. Some also have established an online presence, including using social media.

Dr. Colbert, who has a personal website and a public Twitter account, believes this is savvy, so long as physicians maintain a professional image.

“To gain patients’ trust and confidence in their health care, you can’t just have one social media account that shows your kids and your politics and your vacations, while at the same time doling out health care information,” he said.

Both Drs. Colbert and Chen welcome these industry changes, which they attribute to millennials.

“Medicine is evolving to be more collaborative and more responsive to feedback … especially with the provider shortage created by COVID and the ‘great resignation,’” Dr. Chen said.

This evolution may soon accelerate. The oldest members of Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2012, will graduate from medical school – and age out of their parents’ health insurance plans – in 2024.