At the outset of the 2023 legislative session, San Antonio pediatric anesthesiologist John Shepherd, MD, put on his white coat and marched to the pink dome in Austin to meet with several Bexar County lawmakers.

Although the conversations were wide-ranging, that day in February Dr. Shepherd focused intently on the Texas Medical Association’s top legislative priority this session: stopping scope-of-practice expansions.

“If you allow a system to be divided between those who are highly educated and trained and those who are less highly educated and trained, [patients] with insurance will be able to see physicians, and the ones who don’t [have insurance] will see only the ancillary providers,” he said in each crowded office he marched into during TMA’s First Tuesdays at the Capitol lobbying event. “So, you’ll create a rich man-poor man system, and that’s really the antithesis of what we want to be as a country.”

As expected, scores of scope expansion attempts have again crept their way into the hundreds of bills TMA is tracking.

It’s an issue that affects all physicians and patients, regardless of specialty or geography, says TMA President Gary Floyd, MD.

“It’s not a matter of competition or cutting into revenue,” he told Texas Medicine. “The issue for physicians is that we [as a state] turn lesser-trained individuals on an unsuspecting public, and we are here to serve that unsuspecting public and to protect [them].”

Dr. Floyd, a pediatrician in Corpus Christi, helped TMA broker a landmark state law in 2013 with advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and physician assistants (PAs), which led to an improved model for delegated, team-based care. This model, he says, continues to serve patients well.

But scope expansion legislation continues to surface each session, which Dr. Floyd and other Texas physicians say traffics in misinformation, puts patients at risk, and deflects attention from more sustainable solutions, including expanding graduate medical education (GME) funding and loan forgiveness programs, both of which help address physician workforce shortages. (See “Credit Where It’s Due,” page 40.)

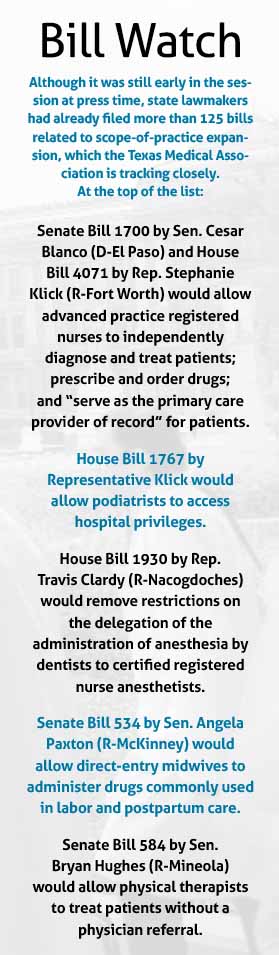

As this story went to press, APRNs as expected dropped a pair of bills just days before the March 10 filing deadline in pursuit of full independent practice and prescribing authority, particularly in rural areas. TMA was already mounting a defense against the legislation and a slew of other bills that would expand scope on behalf of midwives, optometrists, pharmacists, PAs, physical therapists, podiatrists, and other nonphysician practitioners (NPPs). (See “Bill Watch,” right.)

TMA has defeated most scope expansion legislation in the past and must be successful 100% of the time to preserve patients’ access to the highest level of physician-led care, says Chief Lobbyist Clayton Stewart.

“This is our battle this session,” he said. “We’re going to fight, and we’re going to fight hard.”

Dream team

Troy Fiesinger, MD, a family physician in Sugar Land and a member of TMA’s Council on Legislation, also helped advocate for the 2013 team-based care law, which he says simplifies the physician supervision process and fosters collaboration among care team members.

“Before that, it was a complete mess,” he said.

Since its passage, Dr. Fiesinger has relied on the law in his work at Village Medical, a multi-clinic practice where he works “routinely and extensively” with NPPs, including in his role as medical director of a house-call program and a post-hospital discharge program.

As a result, supervising NPPs makes up a significant part of his weekly job duties, including case rounds and chart review. But it’s no longer a bottleneck.

“Scope of practice is not a problem in our organization because we all work together,” he said.

Dr. Fiesinger says the law allows care team members – nurse practitioners, PAs, pharmacists, social workers, and others – to practice at the top of their respective licenses and to shine in their areas of expertise.

For instance, he often relies on nurse practitioners for advice on wound care, while they come to him with questions about medication management.

“Our organization shows clearly how when everyone plays to their strengths [within their scope] … you provide better care,” he said.

In fact, Texas’ team-based care model is so effective, Village Medical adopted the state law as company policy when it expanded into other states.

“It works,” he said.

Myth-busting

Nonetheless, scope expansion attempts persist at the Texas Capitol, where Dr. Floyd says they’re often undergirded by specious claims about fitness, access-to-care issues, and costs.

“There’s significant exaggeration as to what [NPPs] could do if they’re independent,” he said.

Dr. Floyd stresses NPPs are important members of the health care workforce, but he says they aren’t interchangeable with physicians given stark differences in education, training, and exposure to a diverse range of patients.

A physician completes four years of medical school plus three to seven years of residency, including up to 16,000 hours of clinical training, according to the American Medical Association. In contrast, a nurse practitioner completes only two to three years of graduate-level education and 500 to 720 hours of clinical training.

“There’s usually a lot of people who want to do what we do without doing what we’ve done,” he said.

This session, nurses argue they’re the solution to Texas’ primary care physician workforce shortage, especially in rural and underserved areas.

TMA has balked at this claim, citing research showing physicians and NPPs tend to practice in the same areas, regardless of state scope laws.

Dr. Fiesinger says rural and underserved areas struggle to attract physicians and NPPs alike because so many of their residents are enrolled in public health plans, which pay less than private plans, or are uninsured.

“Expanding scope is not going to fix access-to-care [shortfalls],” he said. “You can’t legislate economics.”

NPPs also often claim scope expansion would bring down health care spending. But studies refute this, showing NPPs are more likely than physicians to overuse diagnostic imaging and other services, overprescribe opioids and antibiotics, and over-engage specialists, all of which drive up costs.

The recent experience of Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi bolsters TMA’s case that health care teams should be led by physicians. After 15 years of growing its care teams by adding NPPs because of a shortage of primary care physicians, the clinic analyzed cost data for its accountable care organization, hoping to find it had been able to stabilize cost, preserve quality of care, and maintain patient satisfaction.

“Unfortunately, after nearly 10 years of data collection on over 300 physicians and 150 [NPPs] … the results are consistent and clear,” clinic physicians wrote in the January 2022 issue of the Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. “By allowing [NPPs] to function with independent panels under physician supervision, we failed to meet our goals in the primary care setting of providing patients with an equivalent value-based experience.”

A 2022 study of Veterans Health Administration data by the National Bureau of Economic Research similarly found that compared with physicians, nurse practitioners who treat patients in the emergency department “significantly increase resource utilization but achieve worse patient outcomes.”

Safety first

Bridge City family physician Amy Townsend, MD, has seen some of these findings play out in her own exam room, fueling her concerns about scope expansion and the risks it poses to patients.

In the past five years, she’s noticed an uptick in the number of patients who seek her out after receiving what she described as inappropriate care from an NPP, such as “thousands of dollars” of unnecessary lab work and dangerous supplements from a local hormone clinic. Many of her patients, she adds, weren’t aware they were seeing an NPP before coming to her office, raising questions about transparency.

“A lot of times, I’m having to start from scratch,” Dr. Townsend said. Not only do such workups take a significant amount of her time and drain already scarce health care resources, but also misdiagnosis and mistreatment can cost patients their time, money, health, and even their lives.

“Underserved areas are the exact wrong place for someone with a very limited knowledge base and not a lot of specialty resources,” she said. “[Patients] really should see your best-trained primary care physicians in these areas.”

That’s exactly why the legislature must invest in increased funding for GME, loan forgiveness programs, and rural training tracks, all of which support a more robust physician workforce, Dr. Townsend reiterated.

Early budget bills from both the House and the Senate increase funding for GME residency positions. But Mr. Stewart, TMA’s chief lobbyist, says more needs to be done on loan forgiveness programs, especially those geared toward physicians who train in underserved areas.

Dr. Townsend also worries about how scope expansion might affect patients’ trust in the health care system.

A 2021 AMA survey of U.S. voters found 95% of respondents said it was important for a physician to be involved in their diagnosis and treatment decisions.

“Do they deserve a lesser quality of care?” she asked. “That’s essentially what [scope expansion proponents] are saying.”