Luis Manuel Benavides, MD, was a fan of the accountable care organization (ACO) concept even before the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched a new ACO option for physician practices.

The ACO gives him more time to keep his patients healthy, a tenet he’s always wanted focus on in primary care, the Laredo-based family and geriatric medicine physician says.

“It allowed me to concentrate more on certain values I thought would benefit my patients,” said Dr. Benavides, currently serving as regional medical director for Alpine-ASAS, which first adopted an ACO model in 2017. “Values like prevention and helping our patients be healthier, rather than many other traditional models, where you deal with a patient once they’re already sick.”

His medical group, which specializes in caring for older adults, is now on a new type of ACO he says even more aligns with its goals.

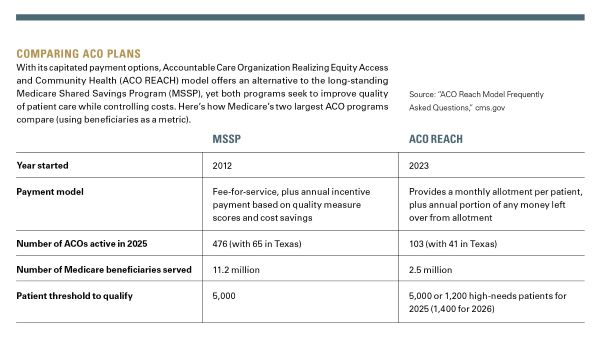

The Accountable Care Organization Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (ACO REACH) model, which started on Jan. 1, 2023, adds emphasis on reducing health disparities and improving access to care for underserved populations.

It’s one of the latest innovations in alternative payment models (APMs) for Medicare, which provide financial incentives to physicians for improving quality and reducing costs, while moving away from traditional fee-for-service models. While ACO REACH is a time-limited test program that will stop at the end of 2026, it could continue beyond that should the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation extend the deadline.

Dr. Benavides got on board with ACO REACH in its inaugural year.

“We thought it offered more opportunities for our population,” he said. “We have a particularly indigent and needy population, and we thought it offered us advantages in taking care of them.”

Unlike the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), in which payment is based on traditional fee-for-service with added incentive payments, CMS pays each ACO REACH management group an allotment covering estimated care costs for the patients attributed to that network. Each individual group then pays its physicians, and should savings be left over from the allotment at year’s end, those are dispersed to the management group and the physicians.

Dr. Benavides characterizes the ACO REACH evaluation of care as “based on outcomes in addition to quality measures,” such as preventing hospitalizations and doing timely follow-ups with patients.

Behind the scenes, he and his staff had a lot to learn – including how to efficiently document patient care and balance a schedule including more routine appointments while leaving room to accommodate urgent same-day ones.

Now that he’s more accustomed to how ACO REACH works, Dr. Benavides hopes the program continues, largely owing to what his patients are experiencing.

“In our second year, one of the things we did as we started doing more [nonmedical drivers] of health when we hired a social worker, was to see if it’s a problem with food and how can that social worker help us to get that patient the food they need,” he said. “If it’s a problem with medication, there are programs out there that help people get the right medication they need. So, all those things are falling into place for us. We’re learning about them, and that is one of the biggest changes.”

Dr. Benavides characterizes this more holistic approach to patient wellness, encouraged by how ACO REACH financially incentivizes physicians, in one simple observation about his patients.

“They appreciate the fact we’re concerned with not just what’s happening right now, but what may happen in the future.”

The Affordable Care Act brought about the MSSP in 2012, now CMS’ largest ACO initiative.

Although ACOs enrolled in the MSSP receive traditional fee-for-service payments, they are incentivized with an annually awarded share of savings for keeping patient spending under a set limit, and incurring penalties when they exceed it.

CMS set a goal of getting all Medicare beneficiaries into accountable care relationships by 2030, and the MSSP has moved it considerably toward that goal.

As of January, “53.4% of people with traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare are in an accountable care relationship with a provider,” according to a Jan. 2025 report from CMS. “This represents more than 14.8 million people and marks a 4.3 percentage point increase from January 2024, the largest annual increase since CMS began tracking accountable care relationships.”

REACH ACOs, though not yet on the enrollment level of MSSP ACOs, are also contributing to this goal.

ACO REACH utilizes two voluntary risk-sharing options: Professional risk, a lower risk-sharing arrangement at 50% shared savings and losses, and global risk, at 100% shared savings and losses. This year, 90 of the 103 participating ACOs went the global risk route.

Southwestern Health Resources (SWHR), a network of more than 7,700 health care professionals (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) spread across a 16-county region centered in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, has a long history as an ACO, Valerie Agena, DO, says.

SWHR converted from a MSSP to an ACO REACH predecessor, the Next Generation Accountable Care Organization model, in 2017, used the Global and Professional Direct Contracting model in 2022, and began ACO REACH the next year when it first became available.

“Our goal is quality care and affordable care. We’re really focused on patient experience because that will drive their ownership in their own care,” said Dr. Agena, SWHR’s value-based care medical director.

The quality measure pillars of the program that align with the ACO REACH model include timely follow-ups (in which a patient sees a physician within two weeks of a hospital discharge), fewer unplanned hospital admissions for patients with multiple chronic conditions, and reduced emergency department visits.

She also notes that surveying physicians to gauge which Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures to prioritize helped them feel more invested by understanding which metrics were important to patient care.

“If [physicians] are going to be responsible for these initiatives, we wanted them to be a part of that decision, to have that autonomy so that they could be successful,” she said. “I really believe primary care physicians are the heart of medicine.”

SWHR’s physicians collectively arrived at a ranked list of HEDIS measures for CMS to evaluate their care that reflects their patient population: controlling high blood pressure, breast cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, hemoglobin A1C monitoring, and kidney health evaluation for patients with diabetes.

While some physicians might be ready to adopt the risk ACO REACH requires, others find MSSP to be a better fit for their practices and patient populations.

“The group of physicians I’m a part of wanted to stay with a limited risk profile,” said Sheila Magoon, MD, executive director of Buena Vida y Salud in Harlingen. “We still have a significant number of physicians who want to limit their downside risk and really want to be in an upside-only relationship.”

As ACO REACH aims to limit hospitalizations to control costs, even a limited number of adverse cases in a smaller patient pool can affect how a REACH ACO uses its allotment. Dr. Magoon notes her group is already mindful of maintaining the 5,000-beneficiary threshold required to contract with Medicare as an MSSP ACO.

“Once you get over about 10,000 patients, then you start mitigating that downside risk, because you’re spreading that risk over a larger population,” the family physician said, adding the decision between being a REACH ACO and an MSSP ACO hinges on asking, “How much downside risk can we absorb?”

Though MSSP uses a more traditional payment route, it still makes physicians mindful of cost-conscious quality health care. Dr. Magoon says analytic vendors have worked with her group to parse data and report on how they’re meeting MSSP’s quality measures, giving them guidance on how they can improve their metrics and gather the shared savings inherent in the MSSP name.

“We have achieved savings for Medicare nine out of 10 years and received shared savings seven of the 10 years,” Dr. Magoon said of Buena Vida y Salud’s track record. “Clinically, we are doing the work. We manage diabetes and hypertension. We evaluate for depression and get mammograms and colorectal screens performed. Those measures we need to map and track are standard, classic, preventative measures we’re doing across the board for every payer. It is very doable.”

Smaller physician groups who want to use a REACH ACO model can partner with organizations that will help them shoulder the risk.

Premier Family Physicians (PFP), an Austin-area group of 27 physicians (plus 14 advanced practice registered nurses and 13 physician assistants), teamed with Agilon Health in 2022 in order to become a REACH ACO.

Gurneet Kohli, MD, PFP’s chief medical officer, says the arrangement has allowed him to hire in-house case managers to improve quality of care, which allow physicians more time with each patient than they would under a fee-for-service model — all helping those physicians to better manage their patients’ health.

“Where some other doctors have to see 30 patients a day, we [each] end up seeing 17 or 18 patients a day, because we know if you take good care of these patients, we’ll get reimbursed for that, and we are able to have a little slower pace,” the Austin internist said. “Our patients really appreciate that.”

The model incentivizes Dr. Kohli to identify higher-risk patients and to make sure a physician in the group sees those patients three or four times a year, which allows patients to develop relationships with those physicians and seek them out when they need to be seen more urgent but before they need an emergency department visit.

“The patients have become more empowered,” he said. “The primary care doctors become more empowered. And they love it.”

Dr. Kohli cites one recent congestive heart failure patient of his who had gained 10 pounds, which turned out to be due to fluid buildup from exacerbation, treatable via medication. Thanks to early intervention, the patient averted a likely emergency department visit, benefiting the patient’s prognosis and the bottom line.

“You need to get a good partner who not only brings in resources, but also brings the technology that helps you see your patients better, and also bring you the right team to guide you,” Dr. Kohli said, crediting Agilon for making data available, along with artificial intelligence tools to help him make better sense of it, and meeting with him regularly to review metrics and identify what his group’s doing well and what needs more attention.

Dr. Kohli thinks controlling costs and keeping Medicare sustainable go hand in hand and sees ACO REACH as a big step forward for APMs.

“I would not want to practice any other way,” he said. “I would be very sad if we didn’t have a value-based program and had to go back to just seeing a maximum number of patients. If you’re a good quality doctor who does high-quality, low-cost care, you should get some benefit from it.”

“If we don’t control costs, Medicare will not be sustainable,” he added. “We have to find a way, and this is a pathway. Could it be better? Yes … but this is definitely a big step forward from 10 years ago.”

Phil West

Associate Editor

(512) 370-1394

phil.west[at]texmed[dot]org

Phil West is a writer and editor whose publications include the Los Angeles Times, Seattle Times, Austin American-Statesman, and San Antonio Express-News. He earned a BA in journalism from the University of Washington and an MFA from the University of Texas at Austin’s James A. Michener Center for Writers. He lives in Austin with his wife, children, and a trio of free-spirited dogs.