All public health initiatives rely on a robust backbone, says Maria Monge, MD, a pediatrician and vice chair of the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Science and Public Health.

In the wake of more than $600 million in pandemic-era federal funding expiring in Texas last year and other public health reductions that have trickled down to the states due to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and other federal actions, that spine could start to crumble without reinforcements in 2026.

“If that [backbone] goes away, there’s no coordination – there’s no ability to distribute resources in an equitable or sensical manner,” Dr. Monge told Texas Medicine. “Everything else kind of becomes moot.”

During the pandemic, the federal government created grants, some funded through the middle of 2026, intended to support immunization initiatives and other health expenses related to COVD-19. However, federal officials allowed state and local public health agencies flexibility in how the funds were used, including directing money toward broader public health priorities, such as measles vaccination programs and improving access to care for low-income Texans.

But now that vital funding has dried up as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) notified in April it was ending public health grants to states made during the pandemic. State officials knew the funds would eventually expire, but most of the recalled money includes grants that were not due to end until mid-2026.

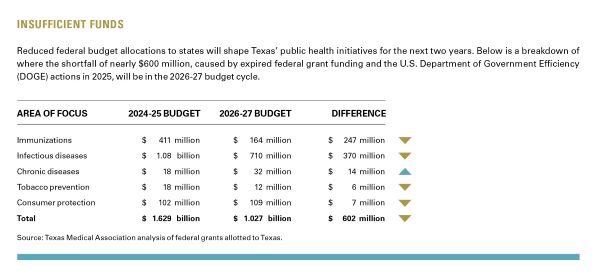

The reduced Texas state budget allocations of federal funds through federal grants and U.S. Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) actions will affect all other corners of public health initiatives in Texas. The National and State Tobacco Control Program was terminated. Infectious disease prevention and surveillance funding dropped by $270 million. Monies earmarked for immunization efforts were more than halved, according to ongoing TMA analyses. (See “Insufficient Funds,” below.)

As a result, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) has made cuts to immunization funding and outreach efforts, also according to TMA analyses.

With funding updates continuing to filter down to the state’s health agencies, the full impact of cascading cuts remains to be seen, though some repercussions are already clear.

As part of the July 2025 passage of OBBBA, the proposed 2026 budget for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was reduced by 53%.

Uncertainty around a pending $200 million Strengthening Public Health Infrastructure Grant (PHIG) is the most concerning unresolved item contained in the proposed OBBBA budget, says Dr. Monge, chair of the Texas Public Health Coalition.

Since its inception in 2022, PHIG funds have allowed Texas public health departments to direct the funds to their most pressing infrastructure necessities, tailoring “resources to meet their communities’ complex and evolving needs,” according to the CDC.

In 2024, PHIG funds helped DSHS modernize its personnel and create a new workforce director position. In 2025, Dallas County Health and Human Services used the flexibility of PHIG funding to provide grants of up to $10,000 to community-based organizations and providers, supporting outreach, transportation assistance, and testing programs to address barriers to HIV services.

As of this writing, the PHIG grant is still pending according to DSHS. With local public health infrastructure budgets having been cut by 25% due to DOGE recommendations in April, many departments have lost an equivalent proportion of staff. If additional federal funding doesn’t materialize, the state will have to devise its own solution to keep public health emergency preparedness robust.

“The cost that will ultimately come back to our state is going to be so far beyond what the cost of these [types of] programs are at present,” Dr. Monge said. “You’re talking 10 years from now, 20 years from now. But if you think about cuts to the vaccines for children, for example, it’s going to be a few years before we start to see how cutting access to vaccine preventable illness shows up in our communities.”

Immunizations outreach slows

With federal monies earmarked for immunization education and prevention efforts this upcoming biennium dipping by 60% due to COVID-19-era public health grants being terminated early, health department staff cuts around the state have already started, says Dallas maternal-fetal medicine specialist Emily Adhikari, MD, chair of TMA’s Committee on Infectious Diseases.

Her county’s health department has a vaccine outreach team that has historically provided childhood immunizations as well as free COVID-19 and flu shots in the community.

In April 2025, Dallas County Health and Human Services laid off 11 full-time and 10 part-time staff as a direct result of funding cuts.

Last year, Texas’ measles outbreak, during which two children died, was the largest single cluster of cases in the U.S. since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000. In June, Bell County Public Health District officials had to temporarily close the district’s health clinic in Temple due to the federal funding cutbacks. That same day, the city reported its first measles case of the year.

“In a post-COVID world where we’ve got a measles outbreak, we’re cutting immunizations. I mean, this just does not make any sense,” Director of the Dallas County Health and Human Services Philip Huang, MD, said, during the agency’s public meeting in June.

The clawback of federal grant monies allocated for immunization efforts will have a cascading effect in combination with state budget changes pertaining to the prevention of infectious diseases.

On top of expiring federal grants for immunizations, funds for the surveillance and prevention of infectious diseases were reduced by more than $300 million by DOGE for 2026-27. The state lost close to $90 million to combat HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

“We’ve had a lot of federal funding awards reduced and also have delays, which has resulted in significant disruption of our services,” John Carlo, MD, told Texas Medicine.

The TMA board member and consultant to TMA’s Council on Science and Public Health said his clinic has lost “a lot of our primary outreach HIV prevention services that have been funded by the CDC for a very, very long time.”

“[Our organization] has had to do staff furloughs and reductions in staff. We’ve had to cancel events and outreach efforts,” said Dr. Carlo, chief executive officer of Prism Health North Texas, a community-based health care organization providing HIV prevention and treatment. “We’ve ended some programs that were very effective.”

He says the ramifications of not having good prevention programs in the highest-risk communities are going to be seen “very shortly.”

“Every time you’re able to prevent an HIV infection, you’re not only really impacting that individual, but you’re also preventing subsequent transmission and further spread,” he said.

On the infectious disease prevention front, there is some positive news for the next two years.

Close to $6 million more funds than the previous state budget were allotted for the prevention and surveillance of tuberculosis cases in the state that could also offset the rising costs of complex treatments for the disease. Nearly $2 million was set aside for congenital syphilis case management. With Texas’ current rate of cases double the national average, in its legislative appropriations request for the 2026-27 state budget, DSHS asked for monies that TMA advocated for to be earmarked for a hotline and a database to track syphilis cases in the state.

“The funding level increase to fight congenital syphilis speaks to how much advocacy and work TMA has been doing around this issue,” Dr. Monge said. “It’s relieving to know a lot of TMA’s work has not gone unheard at all of the levels and also the recognition that congenital syphilis is completely preventable.”

As Texas makes strides toward curbing tobacco use among teens with wins this legislative session limiting the marketing of vaping to teens and vaping devices that look like school supplies, termination of two federal programs could hamper those initiatives.

In April 2025, DOGE eliminated the Office on Smoking and Health (OSH) at the CDC as part of that department’s streamlining of the federal budget. At that time DOGE also scaled back the Center for Tobacco Products at the Food and Drug Administration. Both agencies regulate tobacco products and monitor and attempt to reduce tobacco use.

OSH was the only federal agency to provide funding and technical assistance to state health departments for tobacco control efforts through the National and State Tobacco Control Program. All state tobacco reduction and prevention staff in Texas are funded using federal dollars, according to the American Lung Association. Elimination or significant reductions in programs dedicated to tobacco quitlines, working with K-12 schools to help school kids reject tobacco use, and tobacco surveillance data are affecting Texas, per the report.

But the elimination of OSH could hamper any impetus to reduce tobacco use in the state. Two state programs that funded local coalitions that worked to curb tobacco use in youth have been eliminated, according to Matt Dowling, TMA director of public affairs.

“We do have data that says prevention works and less people smoke,” Mr. Dowling told Texas Medicine. “Health care costs are lower, and people are more likely to quit earlier. Texas still has state funding related to the [tobacco] quit line, but the [federal funding] set aside for advertising and local coalition outreach is now gone.”

The federal agency tasked with reducing the effects of substance abuse and mental illness in American communities is set to lose $1 billion from its budget in 2026 due to DOGE canceling unspent COVID-19 relief funds originally allocated to it. With funding reduced, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) faces cuts that could limit access to vital services – including addiction treatment programs, harm reduction initiatives such as naloxone distribution, and the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline – while also creating funding gaps for state and local programs.

For decades, SAMHSA has supplied essential block grant funding that enabled states to provide critical mental health and substance use disorder services. In Texas, these grants have delivered millions of dollars to sustain mental health programs, peer support networks, and crisis intervention initiatives.

These cuts come at a time when the demand for mental health services has reached unprecedented levels, driven by the lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing opioid crisis, and increasing suicide rates.

The reduction of SAMHSA funding and the folding of it into a new agency, the Administration for a Healthy America, could mean “a radical adjustment and realignment” of the goals of federally funded state programs, according to Austin addiction psychiatrist Carlos Tirado, MD. He also says cuts could potentially mean a limiting of scope for many programs.

“Mental health and substance use services are historically the least funded [public health care programs],” Dr. Tirado told Texas Medicine. “[Those programs] are always the most vulnerable funds whenever municipalities are in a position of having to tighten their belts and roll back or eliminate programs.”

With the new state budget cycle starting, the effects of last year’s federal public health cuts have yet to come into full focus as state and local health departments still sift through impacts.

Looking to 2026 and the effects of federal dollars on public health care initiatives in the state, Dr. Tirado likened this year’s potential events to an offshore storm.

“We know the storm is coming, and it’s going to hit land,” he said. “We just don’t know what the strength is going to be.”

How the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) could transform Texas health care

A Mixed Medicaid Bag: Federal changes may narrow certain Medicaid eligibility provisions, boost others

Immigrant Eligibility Provisions: Federal officials approved these new immigrant eligibility provisions for Medicaid, Medicare, and the Affordable Care Act under OBBBA.

Disrupting the Marketplace: How the ACA expiring tax credits could impact health care costs

ACA in Texas: What parts of the state do Texans carry ACA health plans?

Community Support: Texas aims to use federal funding to address rural health care challenges

One Big Beautiful Bill Act changes: Key modifications introduced by the 2025 federal budget bill – known as OBBBA – that affect major health care programs.

Expanded Flexibility: Patients can now pay for direct primary care with health savings accounts – with caveats

Cap at Hand: Federal loan changes could exacerbate medical students’ financial challenges

How other federal budget items could affect Texas

Concerns Remain: Medicare physician fee schedule retains payment increase and concerning cut