COVID-19 has made a booming illicit business – ransomware – boom even louder. And the more medical practices and organizations fall victim to ransomware cyberattacks, the more illustrative it becomes how important it is to prevent such an attack, which usually goes like this:

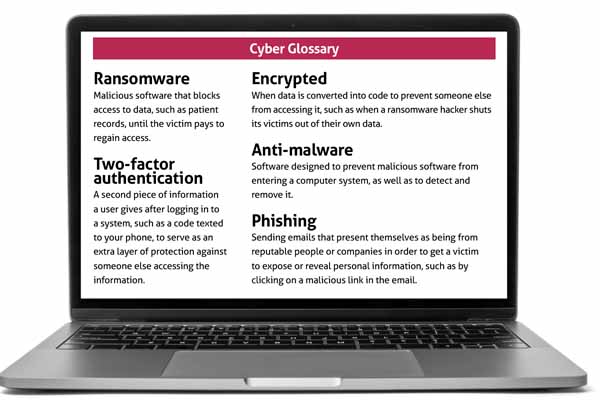

Hackers grab hold of your practice’s electronic patient data, encrypt it so you can’t access it, and demand ransom for its return. And if your data isn’t backed up … well, just don’t let that happen, because your options for recovery won’t be great.

You could choose to not pay the ransom and either hope law enforcement can retrieve your data or somehow press on without any remnants of your patient records.

Or you could pay the ransom, which the FBI doesn’t recommend. Not only is doing so giving in to a cybercriminal, there’s no guarantee you’ll get your records back intact; after all, these are criminals you’re dealing with. And if the hacker happens to be on a special government list that includes terrorists, narcotics traffickers, and others, paying that criminal can leave you – the victim – open to potential civil penalties, per a 2020 U.S. Treasury Department memo.

Although having stout antivirus and anti-malware in place to guard against intrusions is still important, experts say avoiding ransomware today is more a matter of being smart and knowing how to recognize malicious communications disguised as legitimate ones.

In other words, it’s “not truly an IT problem. It’s not a technology problem. It’s a people problem,” said San Marcos family physician Robert Reid, MD, a member of the Texas Medical Association’s Committee on Health Information Technology (HIT). “You can put all the antivirus, all the passwords [with] ampersands and [symbols] like that that you want. But all it takes is for one person to click on an email, or pick up a USB drive, or give someone their information over the phone, and then it’s all over.”

“A pandemic within a pandemic”

Ransomware was already prevalent before the onset of the pandemic. The FBI’s Internet Crime Reports show that from 2018 to 2019, ransomware reports increased by 37%, and associated losses increased by nearly 150%. (See “Ransomware By the Numbers,” right.)

And FBI Supervisory Special Agent Brett Leatherman, of the bureau’s Dallas Field Office, told Texas Medicine the situation has only gotten worse during COVID-19.

“This is a pandemic within a pandemic,” he said. “It is unbelievable the explosion of ransomware over this last year, and the medical field is no exception to that.”

In the first 10 months of 2020, according to a study from Tenable Research, 46.4% of all data breaches in the health care sector were ransomware attacks, and nearly a quarter of all data breaches were on health care facilities.

Cathy Bryant, manager of product development and consulting services for the Texas Medical Liability Trust (TMLT), which insures medical practices against cyberattacks, has seen “a definite uptick” of ransomware incidents in the past two to three years.

Joseph Schneider, MD, chair of TMA’s HIT committee, says that’s no surprise given the transition to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There’s a dramatic increase in these attacks partly because … if your focus is on COVID, and you’re opening up online paths so that people can get to you, it’s no surprise [that] bad guys can take advantage of that,” he said. Even as a victim of such attacks, hospitals or clinics can land on the U.S. Office for Civil Rights’ breach list – informally known as the “HIPAA Wall of Shame” – or in unflattering media reports.

Last year, there were fears that the worst-case effect of ransomware came to fruition in Germany, although authorities later concluded otherwise. A Sept. 9, 2020, cyberattack on Dusseldorf University Clinic forced the transfer of a patient scheduled to receive critical care. The patient died after moving to a facility 19 miles away, according to reports. Prosecutors initially investigated possible manslaughter charges against the cybercriminals. But a couple of months later, authorities announced the patient “was in such poor health that she likely would have died anyway,” according to the MIT Technology Review.

While there aren’t yet any documented cases of ransomware causing a patient death, Dr. Reid is sure it could happen, even if it isn’t an instant death or easily attributable to a cyberattack. He uses the hypothetical example of a patient with a gastrointestinal bleed.

“I need to know pretty quickly what his hemoglobins are so I can give him blood or whatever you need to do. Usually, I can just click on my screen, click ‘hemoglobin,’ done,” Dr. Reid said. “But if there’s something as simple as ransomware in the lab, well … that [hemoglobin] number exists somewhere, but someone may have to print it out from somewhere and just walk it to someone. But I don’t know where the lab is. So maybe I never get access to that data. Maybe it’s delayed by a few hours.”

To pay or not to pay

For practices with no data backups, the decision on whether to pay for the return of ransomed records is a complicated one.

Cathy Bryant of TMLT says if a policyholder reports a ransomware attack, the company assigns a cyber attorney to handle the case and determine whether the practice needs a forensic examination to assess the threat. That examination is typically expensive, she notes. However, if the policyholder makes a timely report, Ms. Bryant says it’s likely the ransomware attack will be covered.

“Once the decision is made, if they are going to pay a ransom, typically it’s the forensics [companies] that negotiate, because they have the most experience in doing it,” she said. In some cases, the hackers end up sending a “test” portion of the data back during negotiations to prove that they have it and can send it back safely. The forensics company then checks that test data to make sure it’s not infected with malware.

In cases where practices “don’t have an adequate backup, then what they find is they may have to pay the ransom,” Ms. Bryant said. “There have been a number of circumstances where ransomware payments had to be made simply so the practice could get back up and running.”

However, that decision recently got more complicated with an October 2020 memo from the U.S. Department of the Treasury that essentially says if you pay a hacker to get your patient records back, and that hacker turns out to be on a government watch list of nefarious characters, you could be violating the law.

According to the memo, Americans are barred from “engaging in transactions, directly or indirectly, with individuals or entities” listed on a specific Treasury Department watchlist, such as targeted companies acting on behalf of targeted countries, as well as non-country-specific terrorists, and narcotics traffickers. And, people who do engage with such entities may face civil penalties, “even if [the person] did not know or have reason to know [he or she] was engaging in a transaction with a person that is prohibited” by the department.

If that sounds overwhelmingly scary, Supervisory Special Agent Leatherman of the FBI is quick to note another part of the Treasury memo, which says the government “will also consider a company’s full and timely cooperation with law enforcement both during and after a ransomware attack to be a significant mitigating factor when evaluating a possible enforcement outcome.”

The FBI recommends contacting the bureau itself if you fall victim to an attack, and the agency will help practices, and insurers or third parties assisting them, to resolve the situation. Mr. Leatherman explains that the FBI doesn’t facilitate paying the ransom but doesn’t hold it against businesses that do.

“The important thing to think about here is where Treasury and the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) and other regulators are analyzing, because there may be penalties down the road,” he said. “Under the Victims’ Rights Act, the doctor’s office is a victim of cybercrime. And we treat all victims as though they’re victims. So whether there’s a ransom payment made or not – I’m an FBI hostage negotiator as well, and the same is true when family members are kidnapped overseas – we recognize there’s a lot of emotion, and folks are going to make decisions sometimes to pay a ransom, and they don’t know what the outcome is going to be.”

How to protect yourself

The best remedy, experts say, is prevention.

HIT Committee member Dr. Reid, whose first degree was in computer science, notes that ransomware generally comes from phishing attacks.The solution is carefully examining emails and other electronic communications to make sure they’re genuine – and not clicking on suspicious links.

“There’s a whole thing in medicine: Trust but verify,” Dr. Reid said. “I would say for IT ransomware, that goes out the window, and it should be: Don’t trust anyone under any circumstances. Even people that have been sending you emails forever, if they suddenly send you a link out of the blue … don’t click on it. Don’t trust anything. Maybe that’s a little extreme, but that’s how you prevent this sort of stuff.”

Another strong safeguard is the use of two-factor authentication.

And Dr. Schneider, chair of the HIT committee, notes the importance of backing up your data: “Have frequent backups. Test your backups,” he said. “Keep a lot of backups, because if the bad guys plant the malware into your system, it might be in several backups going backwards.”

The FBI also stressed the importance of having backups, as well as having them disconnected from the internet.

“The toughest thing that we have is when we go in and folks … haven’t been testing their backups,” Mr. Leatherman said. “At that point, they’re really in a bind. What you’ve done is you’ve said, ‘I’m going to trust a liar, thief, and extortioner to give me my data back when I pay them, and to not re-encrypt me later. We don’t want to be in the habit of trusting bad guys. We want to try to prevent them from engaging in this behavior up front.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(4):34-37

April 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page