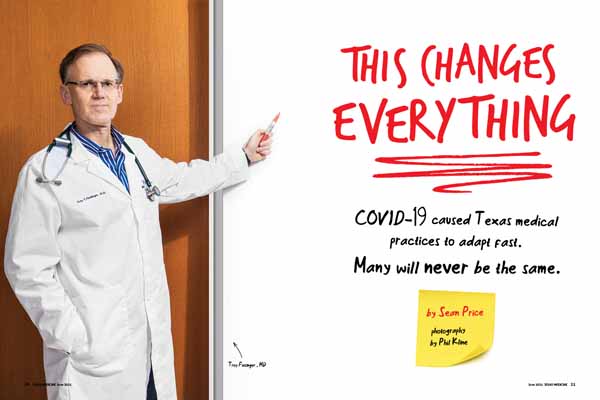

COVID-19’s appearance in March 2020 triggered rapid changes for physician offices throughout Texas. For Sugar Land family physician Troy Fiesinger, MD, the full impact of those changes became clear almost a year later in February 2021 when unusually low temperatures froze the state.

The winter weather knocked out power and paralyzed most of Texas for about a week – an event that would have previously shut down Dr. Fiesinger’s clinic. But after nearly a year of COVID-19, the staff seamlessly switched to working from home.

“When the freeze hit, it was, ‘[Can] everyone can go virtual?’ Good. Without batting an eye, we just did it,” he said.

Adopting telemedicine turned out to be one of the biggest pandemic-inspired adjustments for most practices. (See “The Tele-Future is Now,” July 2020 Texas Medicine, pages 14-19, www.texmed.org/TelemedFuture.)

But other technologies suddenly graduated from interesting side project to urgent priority. And some medical practices made non-technological changes that were just as drastic and likely to become a permanent part of the practice management landscape.

Dr. Fiesinger’s practice, for instance, was already working on a remote patient monitoring app and had to throw those plans into overdrive. Since the app started operation last year, it has identified patients in cardiac distress. (See “Accelerating RPM,” March 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 40-43, www.texmed.org/AccelerateRPM).

“For us, the biggest thing is that there were a lot of ideas we had and then COVID hit, and we just launched them,” he said. “It was the right time and COVID created an urgent need. … I’m a history buff, so the parallel [to the pandemic] I always think of is World War II. There was a tremendous amount of innovation and sociological change because people had no choice.”

For other practices, effective staffing quickly became a major concern. Offices needed employees to work as a team while also remaining safe from COVID-19.

Before the pandemic, the staff working with Austin obstetrician-gynecologist Marco Uribe, MD, did so exclusively in an office setting. But concerns over COVID-19 forced administrative and clinical triage staff to work off site.

That caused difficulties at first, Dr. Uribe says.

“It was a transition,” he said. “Because in the beginning we weren’t able to run down the hall [to the appropriate staff person] and say, ‘Hey, change this.’”

However, staff members became used to communicating via phone, email, and text. And Dr. Uribe saw that the move had both business and medical benefits.

Moving employees off site has reduced overhead costs by 15% since the pandemic began, he says. At the same time, it allowed the practice to use now-vacant offices for medical purposes like exam and ultrasound rooms.

“Not only is administrative staff able to work from home, but some of our clinical staff is working from home, and that’s a huge shift from pre-pandemic [times],” Dr. Uribe said.

Of course, not all changes caused by the pandemic will be embraced once it’s over, says Waco family physician Tim Martindale, MD. That becomes apparent in physician discussions about whether to keep masks once COVID-19 is less of a threat, he says.

Many physicians see masking as an important medical development and plan to use it regularly to prevent other disease outbreaks – especially among medical staff, he says. Others see masks as an artifact of the pandemic and will be glad to get rid of them once it’s over.

“I know that there are some docs here in Waco who feel that [masking is] the norm for the rest of our lives,” Dr. Martindale said. “Then I know others who can’t wait to get back to regular life and pretend [the pandemic] never happened.”

His practice will probably fall somewhere in between, using masks at the start of a visit but giving patients the option of taking them off if there are no symptoms of infection. That will help especially for patients who have difficulty hearing.

“Masks have interfered so much with communication,” he said.

Keeping channels open

Physicians, like workers everywhere during the pandemic, quickly discovered that video communication apps like Zoom and Microsoft Teams were vital for keeping separated employees in touch.

Dr. Fiesinger works for Village Medical, which has 25 clinics that employ 169 health care professionals throughout Texas, he says. The communications apps have helped physicians stay in touch with the larger organization as well as staff members at their own clinics.

“We actually have more [physician] meetings, more clinic meetings, more operating meetings because they’re so much easier to do,” he said.

The apps also helped change attitudes about how to hire staff, Dr. Fiesinger says. For instance, a data analyst in Colorado or Oregon can now easily work for a Texas medical practice, he says.

“It’s certainly broadened our reach to hire people for tasks that have to be done,” he said.

Patients also gained more options for communication, Dr. Uribe says.

During the pandemic, women coming in for ultrasound at hospitals and clinics could no longer bring their partners or family members for safety reasons, and liability concerns prevented them from recording the visits. To accommodate them, Facetime turned into a welcome part of these exams, Dr. Uribe says.

“FaceTime has become a whole new aspect of clinical care that we didn’t experience much of before,” he said.

Physicians frequently use social media to update patients about their practices. But during the pandemic, social media became a vital channel for physicians to inform people about COVID-19, Dr. Martindale says.

“Our patients were desperate, and the voices they were hearing [about how to respond to the disease] were completely unreliable,” he said. “They didn’t know what to believe.”

Dr. Martindale, who has a background in communications, turned to social media – as well as blogging and media interviews – to make sure patients and the general public had medically sound information about COVID-19 and other health matters.

Using social media can take up a physician’s time, he says. A typical Facebook post consumed about 10 to 30 minutes a week to research and write, and he typically did about one a week. On the other hand, it also saved time by cutting down on the number of questions his staff had to field and created a “huge payoff in getting information out there,” he said.

“It’s like anything – if you know somebody personally, there’s more credibility to it,” he said. “I feel like now that people are attuned to [listening to physicians on social media] as a reliable source of information they value, then I can use that for other things, like colon cancer prevention and heart [disease] prevention. …This is a voice that’s been laid in our laps.”

COVID-19 also prompted physicians and patients to more efficiently use tools they already had.

For instance, patient portals are an established medical technology that had been traditionally underused. Before the pandemic, nearly all hospitals offered a patient portal, but a majority of hospitals reported that only about one-quarter of patients used them, according to a 2019 report from the National Coordinator for Health IT (tma.tips/2019PortalSurvey).

There is little scientific data on Texas portal use since COVID-19 was introduced to the state. But anecdotally, physicians say portals quickly became an important way to communicate with patients. These patients could not come into the office and staff often fielded too many calls to return efficiently.

“COVID definitely drove [portal] utilization higher,” Dr. Fiesinger said. “It got some people over the hump of using it. And the people who used it [before the pandemic] used it more and asked more detailed questions. So they used it more heavily and they know its features much better.”

Likewise, the COVID-19 encouraged physician offices to push harder for patients fill out their intake forms electronically before arriving for their visit. That safety measure reduced the amount of time a patient had to physically be at the office, and it turned out to be much more efficient, says Tina Philip, DO, a Round Rock family physician who opened her practice in March 2020.

“We had to do it when we were 100% telemedicine, and so that stuck,” she said. “It’s so much better for our workflow. When they actually do the paperwork in advance, we’ve already got their medical release, we can request their records before they’re here in the office, the staff can put all the demographics in the computer and input all their health history from their records. [Having the paperwork done] just makes it so much easier when they’re physically here.”

Room for change

COVID-19 also profoundly altered a familiar medical institution: the waiting room. Medical practices prioritized keeping patients out of waiting rooms to avoid spreading the disease, and that required them to become much more efficient at scheduling, says Austin pediatrician Kelly Jolet, MD.

As a result, her practice now asks patients and their families to wait outside until they receive a text that an exam room is available. When that happens, only one family member can accompany the patient to meet the physician.

“It’s been great,” she said. “It eliminates the concern that most people have of picking up [another illness] while they’re here … It basically took the waiting room and put it in their cars.”

The system has its challenges, Dr. Jolet says. First, it requires parents to plan ahead for the appointment. It also can be difficult for people who don’t have an internet connection to communicate with the office.

But the practice remains flexible with patients who have unusual needs, and the new process has been well received overall, she says.

“Right now, we’re designing a new office space to be opened in the next year or year and a half,” Dr. Jolet said. “It’s interesting to think about our needs pre- versus post-pandemic, and our waiting room will be smaller. We will not be using as much space for that in the new building.”

While COVID-19 has caused waiting rooms to shrink it has also expanded boundaries of many medical clinics – all the way to the parking lot.

Physician practices and hospitals began offering drive-thru services early in the pandemic for testing and other COVID-19-related services, says Jennifer Fan, MD, chief family medicine resident at Baylor Scott and White Health in Round Rock. It’s not clear if these visits will continue after the pandemic, but they are helpful for those with physical impairments.

“This car visit is almost a reflection of the old-fashioned home visit where you’re meeting the patient where they are,” she said.

Drive-thru visits also work well for quick, simple procedures like vaccinations, Dr. Jolet says. In August 2020, her clinic started doing flu shots in the parking lot, and the results were surprising.

“Instead of doing maybe 20 to 30 flu vaccines in the clinic in a day, we were able to do 600 in a half day,” she said. “It was incredible. … We’ll also incorporate that when we’re able to do large-scale COVID vaccination as well.”

Tex Med. 2021;117(6):40-44

June 2021 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page