When Dr. Floyd was in middle school, his family moved to Midland for his father’s work in the oil industry. Before they left Oklahoma, Dr. Bielstein asked his patient what he wanted to be when he grew up. Dr. Floyd had a retort ready: “I’m going to be a pediatrician like you, so I can be the sticker, not the stickee.”

He remembers Dr. Bielstein laughing and then promising to save a place for him in Oklahoma City if he made it through medical school.

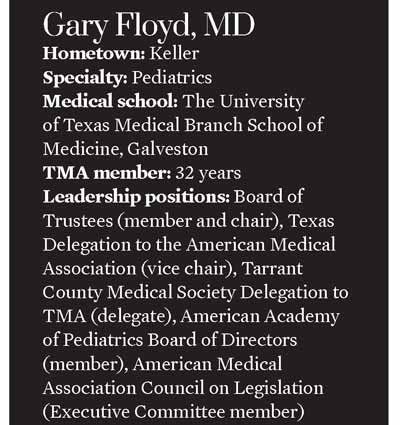

Although their patient-physician relationship was cut short by the move, it found a second life years later. After graduating from The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) School of Medicine in Galveston, Dr. Floyd returned to Oklahoma City, where he completed his pediatric residency at the Children’s Hospital of Oklahoma. His office as chief resident was in the Bielstein Tower, posthumously named for his former pediatrician.

“I don’t ever remember wanting to be something else,” Dr. Floyd reflected. “I was always impressed when [Dr. Bielstein] came out to the house, even though he gave me a shot. He was there to help my folks take care of me.”

Those early interactions laid the path for Dr. Floyd’s 43-year career in pediatrics, which has spanned private practice, academic medicine, emergency and urgent care, administrative medicine, and governmental affairs. This breadth of experience has broadened his perspective and provided a lens into the challenges facing his colleagues in other specialties.

Throughout, Dr. Floyd has remained laser focused on caring for his profession as well as his patients. Since attending his first Texas Pediatric Society meeting as a medical student, he has been an active participant in organized medicine at the local, state, and national levels. Later this month at TexMed 2022, he’ll ascend his biggest platform yet as the Texas Medical Association’s 157th president.

As the fourth president to serve during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Floyd is cautiously optimistic he will be the last. Regardless, he hopes his term will coincide with a profound sense of unity among Texas physicians as they start to redirect their attention from the virus to whatever comes next.

“One of the biggest things we have to focus on is returning professionalism and collegiality to our dealings with each other. The important thing is finding areas of commonality.”

An advocate for patients

Dr. Floyd is as steadfast in that goal as he was in his pursuit to become a “sticker.”

When he graduated from The University of Texas at Austin after three years in 1972, he was the first in his family to earn a college degree. Between his sophomore and junior years, he reconnected with a high school classmate, Karen, who would later become his wife. And during medical school at UTMB, his twin careers in medicine and advocacy started to take shape.

First, Dr. Floyd redoubled his commitment to pediatrics. The only other specialty that tempted him was obstetrics. “But it was fairly obvious that, when we delivered a baby, I’d go take care of the baby, and [staff would] have to remind me, ‘Hey, your patient’s over here,’” he said, referring to the mother.

Second, he and Karen got married, and she introduced him to Christianity – a faith that would prove critical down the line, when he found himself in chaotic pediatric emergency departments and intensive care units, with patients on the brink of death. Growing his faith through regular Bible study helped him with an inner peace in the midst of difficult circumstances.

“It helped me a lot with just my calm,” Dr. Floyd said of this spiritual practice. “In fact, a lot of times, when all crud was breaking loose, I’ve had a number of nurses and colleagues say, ‘You know, when things really get tense, you seem to get quieter and work faster.’”

Third, as a fourth-year medical student, he was introduced to organized medicine. He remembers the chair of the pediatric department telling him, if he stayed involved in advocacy, he would never be alone because “it gives you more voices when you know things need to be fixed [for patients], instead of just you out there, trying to fix it by yourself.”

Together, Dr. Floyd’s work, faith, and family formed the internal value system by which he lives and works, serving as guardrails along his path from medical school to TMA president.

After five years in private practice, he returned as a faculty member to the Children’s Hospital of Oklahoma, where he did his residency and ultimately served as director of the pediatric program. In 1989, he returned to Texas, where he was recruited to develop a pediatric emergency department at Cook Children’s Health System in Fort Worth.

Perhaps a glimpse into the consummate advocate he would become, Dr. Floyd successfully pushed for the emergency department to accept all patients, regardless of their families’ ability to pay, and oversaw rapid growth as the department’s annual patient volume increased more than 10-fold over his 15-year tenure as medical director.

Even as he moved on to a new role as chief medical officer at JPS Health Network, the city-county hospital serving Fort Worth and Tarrant County, evidence of Dr. Floyd’s commitment to patient care shone through.

One afternoon, a tall young man and his mother visited him in his office. The man was a former patient from Oklahoma City. His family and Dr. Floyd’s had lived around the corner from each other and had attended the same church.

Nearly four decades later, Dr. Floyd still remembers when the man’s mother first showed up on his doorstep one afternoon with her then 18-month old son, who was ashen-faced and struggling to breathe. He admitted the very sick patient to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with Haemophilus influenzae, sepsis, and meningitis. Because the boy was too sick to transfer to the children’s hospital 45 minutes away, Dr. Floyd spent two nights at his bedside.

Although the baby lost his hearing, he ultimately recovered and grew into the 6-foot-2 visitor in Dr. Floyd’s office. Reunited years later, the man hugged Dr. Floyd and introduced a cowering 4-year-old. “I just wanted my son to meet the man who saved my life,” Dr. Floyd remembers him saying.

An advocate for the profession

Dr. Floyd’s voice wavers while recounting this story, but he has a reservoir of strength and experience that has served him well in not just his medical but also his advocacy endeavors on behalf of physicians and patients over the years. Those endeavors include milestones such as the passage of the Children’s Health Insurance Program in 1997 and Texas tort reform legislation in 2003.

His recipe for successful advocacy boils down to teamwork, a prime example of which was the agreed-to bill he helped TMA broker with advanced practice nurses and physician assistants (PAs) in 2013. The landmark compromise led to an improved model for delegated, team-based care. (See “Buried in Paperwork,” May 2013 Texas Medicine, pages 14-20.)

“We were working with [former state Sen.] Jane Nelson [R-Flower Mound] when she was chair of the Senate health committee, before she moved to finance, and she said, ‘Look. We need to get this done,’” Dr. Floyd recalled.

TMA was able to get that job done relying on the expertise of physicians like Dr. Floyd and the relationships he and others had cultivated over the years with nurses, PAs, and legislators.

“The biggest thing with advocacy is, know the decision-makers, know your issues – the pros and the cons – and find the team you’re going to work with,” he said. “The other part of that [team-based care legislation] that was very key was, we had a couple of physicians who had practiced as midlevel providers before they went to medical school, and they gave outstanding testimony as to the difference in their education, their training, and their experiences. So, I think all of that combined was a full team effort. That’s where we achieve the most meaningful changes.”

Successful advocacy doesn't happen overnight; it depends on unwavering, grassroots commitment, Dr. Floyd adds.

“It’s not that you have special abilities. It’s just that you keep showing up.”

Especially during a pandemic and entering into yet another legislative session starting in January 2023, Dr. Floyd exhorts his fellow TMA physicians to exercise those same principles of teamwork among themselves.

He empathizes this with his colleagues when it’s “not as easy to keep the focus on patient care” in the face of pressures from insurers, hospitals, and regulators, let alone a pandemic.

“Many of my colleagues – and I – have learned that hospitals [and insurance companies] have to look out for their bottom line,” he said. “They’re not there to look out for their physicians, and sometimes they’re not necessarily there to look out for the patients.”

And as the COVID-19 pandemic languishes into its third year, physicians are left struggling with record levels of burnout and newfound contempt for medical expertise. The early months of the pandemic – when scientists, public health experts, and physicians scrambled to respond to the new virus, changing course as new evidence became available – have cast a long shadow.

“It can often look like, to the public, that we’re not in agreement, which leads to public mistrust and frustration that they don’t know who to believe,” he said. “Then, when they mix that in with all the nonsense on social media, it really confuses them.”

Dr. Floyd knows all too well that medicine’s enemies and political gamesmanship are the only beneficiaries of divisiveness within the House of Medicine.

A united front

These types of challenges make professional unity all the more important, Dr. Floyd says, and he is sure physicians are up to the task of reclaiming common ground by fostering trust and collaboration within the profession.

Now that hospitals have cut back on staff meetings and physician lounges, for example, “it’s very important that physicians take it upon themselves to interact with their colleagues beyond just in taking care of patients,” he said. “We [physicians] used to meet at the general meetings, sit and discuss things in physician lounges, and hardly ever do you do that anymore. So now it’s very important that we’re getting out in our county medical societies, that we interact with our colleagues, share ideas, and realize that in our membership, we have a great diversity of opinion. And that’s fine. But when we say we bring 56,000 voices, we need to focus on those key areas where we have commonality.”

As just a start, Dr. Floyd said those commonalities include “protecting the sanctity of the patient-physician relationship; allowing physicians to be physicians without having to worry about interference from insurance or other payers or the government; protecting our patients as they seek assistance for delicate problems; [and] protecting our physicians as they try to render care to the best of their abilities.”

He also reminds physicians that often the eyes of the nation are upon Texas and TMA as a leader.

As just one example, the long-time member of the Texas Delegation to the American Medical Association said TMA, through that delegation, “networks and develops friendships with docs all over the country, and that’s been very important for us as we push national issues. I can’t tell you how many people from all over the country – physicians and associations and hospitals – ask, ‘How did you all achieve that?’ – and have congratulated our team.” (See "Amplified by AMA," page 33.)

“We are blessed that Texas has amazing expertise in all areas,” he said, adding that he wants to see physicians harness that expertise in solidarity.

He also wants TMA members to know that the association is here for all physicians, whether employed or in independent practice, whether by providing tangible resources, such as masks, or by taking legal and legislative action.

“I hope our docs understand TMA is here for them, and we’re here for our patients,” he said.

Tex Med. 2022;118(3):18-23

April 2022 Texas Medicine Contents

Texas Medicine Main Page