For Uvalde family physician Erika Beatriz Garcia, MD, May 24, 2022, is one of those days you never forget.

“I was at work and on a lunch break listening to some of my coworkers talk about Facebook and about this [school shooting] happening, and then I got a text from my father, who lives three blocks away [from the school], saying that he could hear gunshots,” she said. “I then got a text from our emergency response system at our hospital that was asking for me to please stand by just because there was an active shooter situation in the community.”

The shooter killed 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in this city of about 16,000. Not surprisingly, the emotional fallout has been broad and deep.

“The number of people affected is campuswide and citywide,” she said. “Some of those kids who are having a really hard time going back to school and being worried about if it happens again weren’t even on that campus that day. They fear for their lives, and the idea of security has affected a huge segment of the community.”

The Texas Medical Association quickly reached out to local physicians to see what they needed, just as it did during the COVID-19 pandemic and after other disasters, says TMA President Gary Floyd, MD, a Fort Worth pediatrician. TMA also mobilized the private organizations, businesses, and state agencies that would be most effective in handling this emergency.

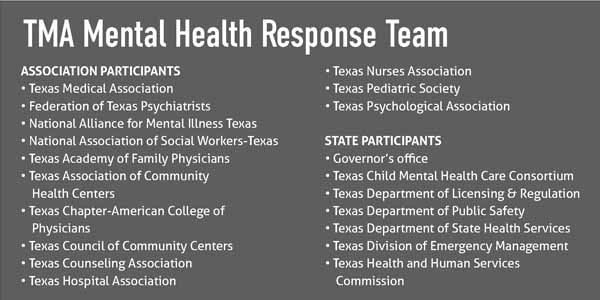

That led to the formation of the Texas Mental Health Response Team, a coalition of about 20 entities, to identify needs in Uvalde and answer them as quickly as possible. (See “Texas Mental Health Response Team,” page 29.)

The response team meetings showed that TMA’s foresight in fighting legislatively for improved mental health programs has paid off in the Uvalde response, says David Lakey, MD, presiding officer of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium (TCMHCC). For instance, TCMHCC – which the state established in 2020 with TMA’s strong backing – worked through the Texas Health and Human Services Commission to provide mental health professionals to the Uvalde area.

“The local mental health authority [in Uvalde] was just a block away from the school, and so the people [there] heard what was going on and a lot of times had kids who were at the school,” he said. “So, they were victims of the event. They had a very high vacancy rate [after the shooting], about 40% … and they were asked to respond – which is a very tough situation.”

At the request of the authority, TCMHCC sent teams of psychiatrists and other mental health care professionals to meet the needs of the community and its own staff members, Dr. Lakey says. Texas has certainly had other mass shootings, most recently those in Sutherland Springs (2018), Santa Fe (2018), El Paso (2019), and Midland-Odessa (2019); that kind of assistance would have been much harder to coordinate before TCMHCC was established in 2020.

“This resource that we had through the consortium was a new and unique capability of the state,” Dr. Lakey said. “It’s the first time we’ve been able to collaborate on something like that and to help … and it will be used again in the next disasters that occur.”

The TCMHCC assistance is ongoing, he says. And TMA and other organizations also wanted to make sure that the response to Uvalde is not a one-off, temporary measure that disappeared in a few weeks, says Beaumont anesthesiologist G. Ray Callas, MD, chair of TMA’s Board of Trustees.

While most efforts are focused on helping Uvalde recover, the TMA response team – which now meets quarterly – also is determined to promote preventive efforts that might help halt or mitigate the impact of future disasters in all Texas communities, he said.

“We’re trying to make sure this is not just an acute response [to the Uvalde shootings],” Dr. Callas said. “It’s a chronic response in which we come up with a playbook on how behavioral health is treated” in all disaster situations.

Many of the specifics for that playbook are still being thought through, Dr. Floyd says. They will be spelled out in the months and years to come as physicians understand what works best when addressing mass shootings and other types of disasters.

That could involve state legislation designed to improve counseling services to help recognize someone who is troubled, Dr. Floyd says. It also could include money for improved school safety measures, and better education about gun safety and ownership.

TMA will push for legislative funding for statewide outreach, Dr. Callas added.

“We’re also trying to come up with ways that we can get our message out throughout the state of Texas to other school districts to help prevent these types of mass casualty situations,” he said.

In June, Lubbock pediatrician Celeste Caballero, MD, testified for TMA and several specialty societies at a hearing of the Senate Special Committee to Protect All Texans – formed in response to the Uvalde shooting – and outlined TMA’s approach to preventing future gun violence. TMA is asking lawmakers to:

• Support and bolster the state’s mental health care system. That includes not only the state’s roster of psychiatrists – which, by one estimate, is short of what Texas needs by about 1,000 – but also the primary care physicians who are “generally the doctors that families are seeing first for mental health care,” Dr. Caballero said in her testimony.

• Enhance family-child interventions and augment investments in social services to build “strong, resilient Texas families,” Dr. Caballero said.

Conversations that Drs. Floyd and Callas had with physicians and health care professionals in Uvalde, however, showed there are more immediate concerns for an emergency response – in Uvalde and at the sites of future disasters.

“One of the messages we heard pretty loud and clear is that they were inundated with well-meaning people who were volunteering to help, but they had no way of vetting those people to know if they were really who they said they were,” Dr. Floyd said.

Two local entities – the city of Uvalde and Uvalde Memorial Hospital – received offers to volunteer from dozens of people from around the country, Dr. Garcia says. Because neither entity was set up to vet those volunteers, two kinds of problems emerged: First, qualified volunteers found it more difficult to help and, second, local physicians found it difficult to match patients with the volunteers who could help most.

“I corresponded with a clinical traumatologist who provided an educational resource, and then sought my professional endorsement for dispensing a proprietary blend of biologics that wasn’t studied in published medical literature,” she said. “I asked a community volunteer for counselors to meet my patients and was sent chaplains. Verifying licensure and credentials mitigates the risk that people seeking aid are not inadvertently routed away from the kind of aid they seek.”

The psychological help Uvalde residents need in many cases is not complicated, but it is vital that they receive it, says Dallas psychiatrist Sabrina Browne, MD. In June, Dr. Browne accompanied a UT Southwestern Medical Center team of behavioral health care specialists as part of TCMHCC’s assistance.

“One of the things that I heard that just broke my heart was that a lot of people would say, ‘I don’t know if I should be here. I don’t know if this [mental health service] is here for me. I wasn’t directly involved. I wasn’t there that day. My child wasn’t there. But I just really need to talk to someone.’”

Texas physicians need to understand that the psychological impact of the Uvalde shooting already has reverberated in other parts of the state and that young people in particular are affected, Dr. Browne says. Physicians who don’t have a background in psychiatry can still help those patients.

“You don’t have to have the answers; you don’t have to have the solutions,” she said. “It’s about creating that space where [young people] can talk about what their concerns are and giving them that reassurance that they’ve got parents, family, school behind them to support them.”

TMA officials spoke with physicians and physician organizations that dealt with previous school shootings, including those involved in the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting in Sandy Hook, Conn., in 2012, Dr. Floyd says. They made it clear that the residents of Uvalde will face repercussions from the shooting for years to come.

“We’ve learned from talking to the people up in Connecticut that some of them are just now graduating high school and some of them are still in counseling and many of the community inhabitants are still in counseling 10 years later,” he said. “Every time there’s a holiday or a birthday or something like that, it all comes back.”

All disasters can create lifelong trauma, and each disaster has unique characteristics, Dr. Floyd says. (See “Lessons From Uvalde, page 30). So, the Mental Health Response Team’s playbook will have to provide a versatile roadmap for physicians to prepare for the next one when it comes.

“It’s not a matter of if,” he said. “It’s a matter of when.”

Lessons From Uvalde: Remove Barriers to Care

PHYSICIANS AND OTHER HEALTH CARE professionals have tried to respond nimbly to the crisis in Uvalde. One of the biggest lessons from the tragedy, however, is that Texas’ health care system does not adjust well, even in emergencies, says Uvalde family physician Erika Beatriz Garcia, MD. For instance, many health care professionals have tried to offer their services at low cost or for free, but patients frequently run into some of the same roadblocks to care that paying patients face. “We have an outpouring of counselors available right now. It’s the coordination that’s keeping them apart from the patients,” she said.

How can the situation be improved? Here are some lessons learned from Dr. Garcia.

Curtail paperwork in a crisis.

Minimizing forms by using verbal consent to treat as appropriate and skipping the front office and insurance forms when providing direct care free of charge helps “tremendously,” she said, especially “when [the patient] can’t sit still because they’re so on edge.”

Connect patients with help directly and quickly.

State agencies and organizations offering help also have had trouble responding quickly. That became clear when she called the state’s established “crisis line” for Uvalde on behalf of a patient who needed urgent psychiatric help. Instead of reaching a health professional, she was connected to an administrator with a list of offices around the state. It took five days of jumping through hoops to connect the patient to care.

Have a local communication plan.

Uvalde, like a lot of small cities and towns, does not have a centralized media outlet that covers all segments of the population. That meant many services – like those offered by the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium – were poorly communicated to local patients and physicians. Also, Dr. Garcia says many people in Uvalde have no health insurance or regular access to health care, which often serve as sources of help and information.

Be aware of stigma.

Some people may be sensitive to the stigma of accepting counseling. Instead, focus on its benefits. “I’ve had patients tell me that their family told them, ‘You don’t need counseling, get over it.’ But if you say, ‘We can help you sleep through the night. We can help you be able to eat regularly again. We can help you enjoy being around other people. We can help you feel safe in crowds.’ That’s going to reach a group of people who might not recognize what counseling can provide,” Dr. Garcia said.

Don’t withdraw help too soon.

Counseling is often needed even more as the trauma of an incident like the May shootings sinks in. And the range of response will be “as varied as human biology allows,” she said. “I’ve had some patients who were profoundly affected in the first few days and were not able to return to duty, and I’ve had some patients who I had no idea had been shot at.” But, she added, “There are going to be people who don’t have any inkling that they’ll need medical help for what they’ve experienced until six months in.”