Lubbock psychiatrist Sarah Mallard Wakefield, MD, first got interested in the mental health distress among mothers early in her medical career during a fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry.

“Many, many of the mothers would come in and have an untreated pathology and had been long suffering,” Dr. Wakefield, chair of psychiatry at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, told the Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee (MMMRC) at a recent meeting. “They would spend the time and energy to get their children services, but they would not spend the time and energy on themselves.”

That dynamic – mothers ignoring serious mental health issues – has been shown to be a fatal problem for Texas women of childbearing age, according to the committee’s 2020 report with the Texas Department of State Health Services on maternal death and illness.

“Mental disorders, including those associated with substance use disorder, were a leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related death and occurred most frequently between 43 days to one year postpartum,” the report stated. The answer it provided: “Integrated behavioral health care, where behavioral health and maternal and women’s health care providers work together to provide high-quality care, can mitigate the risk for suicide or unintentional overdose.”

Providing that kind of care is the rationale behind the Aug. 18 launch of the Perinatal Psychiatry Access Network, or PeriPAN, a pilot expansion of the Child Psychiatry Access Network that began in 2020. (See “Making the Right Call,” November 2021 Texas Medicine, pages 26-30, www.texmed.org/CPAN2021.)

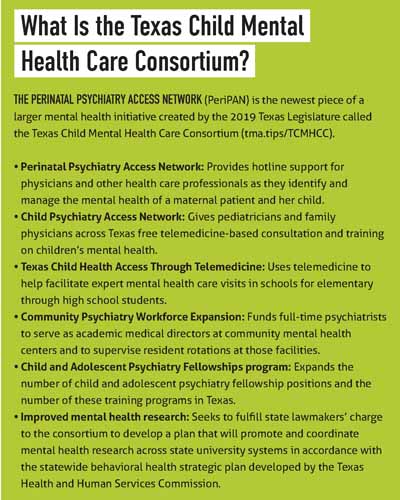

CPAN gives pediatricians and family physicians across Texas free telemedicine-based consultation and training on children’s mental health. A pediatrician or family physician caring for a patient with psychiatric needs can call CPAN and typically get professional advice in minutes.

PeriPAN’s hotline and network work the same way, says Dr. Wakefield, the program’s medical director. It gives prompt, phone-based consultation on case management, diagnosis, and medication management in cases of perinatal mental health. It also helps guide physicians to the best resources and services for mothers and provides training and education for reproductive mental health services.

The Texas Legislature created CPAN in 2019 and PeriPAN in 2021 as part of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium (TCMHCC), a larger group of programs focused on improving psychiatric care for young people. (See “What Is the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium?” page 40.)

Ignoring or undertreating maternal mental health needs is expensive. Texas spends about $2.2 billion each year helping young mothers and their children deal with maternal mental health conditions and their consequences, such as preterm births or ensuing child developmental disorders, according to a 2021 report by Mathematica, a nonpartisan research organization based in Princeton, N.J., that focuses on improving public health. That amounts to about $44,000 in societal costs per mother and child from conception until age 5, the report said.

PeriPAN’s counseling goes hand in hand with TCMHCC’s original mission of improving children’s mental health, Dr. Wakefield says.

“We know that when we support the mental health of mothers, we support the mental health of children,” Dr. Wakefield said. “They are linked, and they cannot be unlinked.”

PeriPAN – like CPAN – is based on a Massachusetts model started in 2004 and now copied in 17 other states, according to the UMass Chan Medical School. PeriPAN’s purpose is to:

• Support physicians and other health care professionals as they identify and manage a patient’s mental health;

• Expand access to education about maternal mental health disease and effective treatments;

• Improve the mental health care and systems of care for women who are pregnant, postpartum, suffering perinatal loss, or planning pregnancy; and

• Improve the mental health care for children and adolescents of Texas by supporting the women who care for them.

Similar to Massachusetts – but unlike in some small states – Texas’ version of CPAN breaks the state into regional hubs.

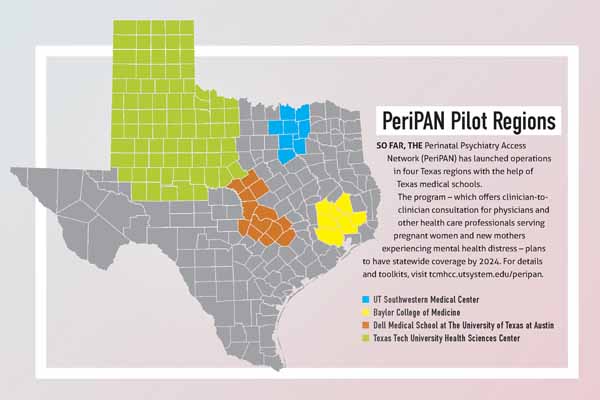

So far, four of PeriPAN’s proposed 12 Texas hubs are operational. Because Texas is big geographically and has such a diverse population, launching each hub becomes a major undertaking – akin to a statewide launch in a smaller state, Dr. Wakefield says. (See “PeriPAN Pilot Regions,” above.)

Funds from the federal American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 provided the money to get PeriPAN started, she says. But the program plans to request state funding to become fully operational in all 12 regional hubs by 2024.

In each region, PeriPAN – like CPAN – partners with a university-based department of psychiatry that provides consultation to family physicians looking for answers about patients’ psychiatric symptoms. PeriPAN expands that mission to serve obstetricians and other clinicians who care for women during pregnancy and postpartum.

When physicians enroll in PeriPAN, they can call their regional hub for free and as many times as needed. A licensed counselor answers the phone. Depending on the physician’s needs, the counselor may provide resources, give a referral for therapy or other services, or connect the physician with a reproductive psychiatrist. Typically, a mental health professional and the physician discuss the case so they can draw up a treatment plan.

“You don’t have to be seeing a patient in your office to call about their care,” Dr. Wakefield said. “Many [clinicians] call us and then call the patient back later after they have formulated a plan” with PeriPAN’s help.

The physician’s time on these calls is billable for payment through health plans, she says. Because the calls increase the complexity of the visit, they can be billed at a higher CPT code.

PeriPAN does not yet have participation data available, but it needs the same kind of reception Texas physicians have given CPAN, Dr. Wakefield says. Physician participation in CPAN has soared over time, jumping from fewer than 100 consultations per month in September 2020 to just under 800 per month in May 2022, according to TCMHCC data. “What I ask of you is that we talk about this program, that we get clinicians engaged, utilizing it, and then get feedback,” she told MMMRC.

In an ideal world, Texas and other states would be able to provide enough psychiatrists, counselors, and other mental health professionals to address all the state’s needs, Dr. Wakefield says. But that’s simply not possible right now.

“There is a drastic mental health professional shortage across the nation and also in Texas,” she said. “So, we’re looking at other evidence-based creative ways to improve outcomes for maternal mental health care as well as children’s mental health care.”

Like CPAN before it, PeriPAN can give a hand to physicians who recognize that a patient needs mental health resources that aren’t readily available, Dr. Wakefield says.

“We want to help you when your other option would be to do nothing, doing something that you’re unsure of, or having a woman or a child sit on a waitlist for several months [to get psychiatric help] and getting no care and worse over time.”