Every physician can look around and see some policy change or improvement that could make life better for patients and colleagues.

The Texas Medical Association’s House of Delegates, the organization’s highest policymaking body, is often the best place to set that reform in motion.

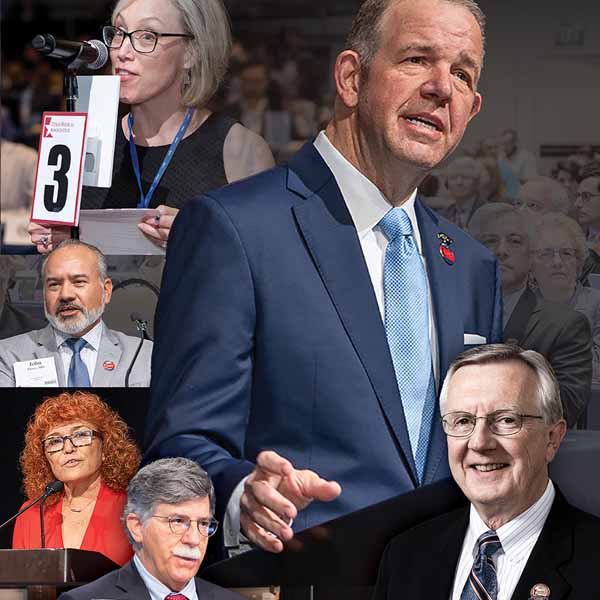

“We have a practice-friendly environment here in Texas. That’s due to many of the policies developed in the House of Delegates,” said TMA Speaker Bradford Holland, MD, an otolaryngologist in Waco.

Policies addressed by the house may involve specific, localized ideas that might affect a certain segment of Texas’ physician or patient population. But the house also serves as a forum for big proposals that trigger physician-driven change at the state or federal level, Dr. Holland says.

For instance, in 2021, the Texas Legislature approved a new law allowing Texas physicians to earn a "gold card" out of prior authorizations by demonstrating to insurers that they consistently earn approval for a particular service. TMA policy created in 2019, along with aggressive advocacy, helped kick off work with Texas lawmakers that made this groundbreaking law possible, Dr. Holland says.

Physicians looking to propose a resolution should first check to see what TMA’s existing policy is on the subject, says TMA President Gary Floyd, MD, a Keller pediatrician. TMA provides a policy compendium that allows members to look up any topic to see the organization’s current stance. (See “House of Delegates Resources,” below.)

“They may find that what they’re concerned about is already addressed,” Dr. Floyd said. If not, then looking it up “would be a good start” to enacting change.

Assuming the topic has not been properly addressed, a member should then do research and discuss the topic with other TMA members, starting with colleagues and members of the local county medical society, says Little Elm internist John G. Flores, MD, vice speaker of the house.

Physicians should cast the net wide in getting advice, he says. That means also speaking with members of a relevant TMA caucus, TMA sections, councils and committees, and specialty societies. It also means talking with relevant TMA staff.

That research might be time-consuming, but it typically pays off because it tells the resolution writer what policies are most likely to be approved by the house, Dr. Flores says.

“Say you have an idea about how a nursing home should be run,” he said. “The logical next step would be to contact that committee, talk to their [TMA] staffer, talk to the chair of the committee, and develop that idea. It might be an idea that’s never been out there before, so you’ll want to put that in resolution form, and that [TMA] staffer can help you.”

Following this process will prevent the member from wasting time on efforts that are unlikely to pass or duplicate previous work, he said. Also, getting wider buy-in is essential for getting the resolution approved. While any member can write a resolution and testify on its behalf, only voting members of the House of Delegates, county medical societies, and TMA sections can introduce a resolution to the house.

Given all the need for widespread feedback, each resolution writer should be open to potential changes at any step in the process that might make the measure more likely to win house approval, Dr. Holland says.

Once the research is done, physicians who sit down to craft a resolution have to keep in mind the No. 1 rule for all writers: Remember your audience.

The first audience will be one of four reference committees made up of physicians chosen for their expertise in science and public health; socioeconomics; financial and organizational affairs; or medical education and health care quality.

The reference committees typically do much of the vetting of resolutions – hearing testimony, asking hard questions, and probing for unintended consequences of a proposal.

“Even if you have a good idea, it’s easy to not appreciate all the ramifications,” Dr. Holland said. The reference committee is where “most people have their eyes opened to what this resolution could really do and what does this really mean. … It is the [reference committee’s] job to mold it into the best version of your idea that it can be.”

The reference committee can recommend to the house that the resolution be adopted, adopted with amendments, not adopted, referred for further study, or referred for a decision by the TMA Board of Trustees or Board of Councilors. Because the house meets for only a couple of days each year, most resolutions get a vote based on those recommendations. But some of them are “extracted” for further debate on the house floor.

Resolutions can face amendments in both the reference committee and the house, and the best way to prevent confusion during that process is to keep the writing short and simple, Dr. Flores says.

“A simply stated resolution with clear language should be the goal in resolution writing,” he said. “This will decrease any ambiguities. Taking the extra time to write a well-worded resolution will pay dividends later.”

In considering a resolution, a reference committee first hears online testimony from the author, who also submits written material supporting the resolution. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the entire TMA policymaking process was conducted virtually, which proved unwieldy, Dr. Holland says. But during those years, TMA found that taking the initial testimony online was an effective way to iron out problems early, and TMA made that part of the virtual process permanent.

“We’re ending up with a better quality of resolution by the time it hits the house floor, and that’s made the house more efficient,” Dr. Holland said. “There are fewer on-the-floor amendments, less getting in the weeds of parliamentary procedure in amending and striking and substituting. We have resolutions that are vote-ready, by and large.”

After the online testimony, the committee writes an interim report on what it thinks should happen with the resolution and then holds a live hearing to address the report. At that point, authors must be ready to defend their measure against critics, but they also have to be ready to respectfully hear out opponents and to compromise.

“This is old-fashioned debate,” Dr. Holland said. “You need to be ready to put your points forward and be ready to refute those that are against you.”

The reference committee wraps up its business by sending a final report on the resolution to the house, including a recommended action. What happens in the live reference committee is frequently a preview of what happens on the house floor, where between 300 and 400 delegates – fellow physicians – will vote on the resolution during TexMed, TMA’s annual policymaking conference.

Typically, only a few resolutions are taken up, or extracted, by the house for further debate and discussion, usually because there wasn’t consensus among delegates with the reference committee’s recommendations.

Because TMA is a broad, politically diverse coalition of physicians, even seemingly good ideas might not get widespread support in the house because they appear too partisan or inflammatory, says Houston internist Lisa Ehrlich, MD, a member of the TMA Board of Trustees.

Resolutions that don’t focus directly on the practice of medicine and helping patients typically don’t win approval.

“When you bring a resolution, there needs to be a problem that’s solvable and that [physicians] can have an impact on,” she said.

Most of the time, the house follows reference committee recommendations. But that’s not always the case. In 2022, of the 32 resolutions that were adopted, two were adopted without a reference committee recommendation to do so. Of the 19 that were not adopted, two had been recommended for adoption by the reference committee. Meanwhile, one resolution the reference committee recommended for adoption became one of the 19 resolutions the house referred.

“If the reference committee has voted in favor of adoption, that is a pretty good vote of confidence for you,” Dr. Holland said. “But of course, as with anything, you never know. The will of the house could be different from the will of the reference committee.”

Although the main mechanism for policymaking, resolutions are not the only house’s only tool. TMA boards, councils, committees, and sections also develop ideas and recommend actions through reports to the house.

For instance, one 2022 report written by the Council on Socioeconomics and two committees – and approved by the Reference Committee on Socioeconomics – called for TMA to advocate for payer health policies that ensure telehealth coverage does not discourage the use of local physicians.

House-approved resolutions join the TMA Policy Compendium and are assigned to the relevant board, council, or committee for implementation. Depending on the nature of the resolution, it might be referred to TMA’s advocacy arm to lobby for state legislation, sent to the American Medical Association to initiate federal lobbying, launch a task force, or prompt community action – among other possibilities.

Resolution authors can help their case immensely by understanding the rules of parliamentary debate, Dr. Holland says. Both the reference committees and the house follow the American Institute of Parliamentarians Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure. It also helps to study the TMA Handbook for Delegates.

“There needs to be some familiarity with those processes and realize it can be a little bit cumbersome even if people think your idea is good,” Dr. Holland said. “If we get too lost in the parliamentary procedure, everybody gets piqued on it.”

Just because a resolution isn’t adopted by the house – or isn’t adopted right away – doesn’t mean it fails to have an impact, Dr. Ehrlich says. She authored a resolution encouraging TMA to find better ways to streamline prior authorizations. So far, it’s fallen short of adoption since she first submitted it to the house in 2017. But her work on it helped lead to discussions with both TMA staff and fellow members – as well as key state lawmakers – that kept the prior authorization issue front and center, enough so to feed success in another areas, like the gold-card law.

Change often comes slowly, so resolution writers need to think long-term, Dr. Ehrlich advises. Since the house meets annually, any physician whose measure does not win approval there can study the issue further, find new ways to approach it, and try again.

“If it doesn’t work, bring it back the next year and have all your arguments honed,” she said.